The Medical Library Association (MLA) held a hybrid meeting in Portland, Oregon from May 18 to May 21, 2024. Many of Hardin’s librarians participated in the meeting. This year’s meeting marked the end of Hardin Director Janna Lawrence’s three-year term on the MLA Board. Hardin librarian Mary M. Thomas presented a program overview of theContinue reading “Hardin Staff participate in 2024 Medical Library Association meeting”

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Duncan Stewart wins Benton Award for Excellence

Congratulations to Duncan Stewart, the of Libraries’ Cataloging-Metadata Department who has been selected to receive the 2018 Arthur Benton University Librarian’s Award for Excellence. Duncan’s nominators called out his work in bringing a cataloging class back to the University of Iowa School of Library and Information Science (SLIS) as well as his efforts to expandContinue reading “Duncan Stewart wins Benton Award for Excellence”

PubMed Food Problem: Cruciferous Vegetables

To do a PubMed search for cruciferous vegetables that includes such species as Radish and Arugula, each species must be done separately. By Eric Rumsey, Janna Lawrence and Xiaomei Gu In order to do successful searches for cruciferous vegetables in PubMed, it helps to know exactly what “cruciferous” means, which makes it easier to understandContinue reading “PubMed Food Problem: Cruciferous Vegetables”

Plant-Based Foods – A Tricky PubMed Search – Revised 2016

By Eric Rumsey, Janna Lawrence and Xiaomei Gu As we discussed in an article earlier this year, searching for nutrition in PubMed has improved greatly since NLM brought the subject together in one explosion (Diet, Food, and Nutrition). This ability to search the field of nutrition easily has helped in searching for plant-based foods [PBFs]Continue reading “Plant-Based Foods – A Tricky PubMed Search – Revised 2016”

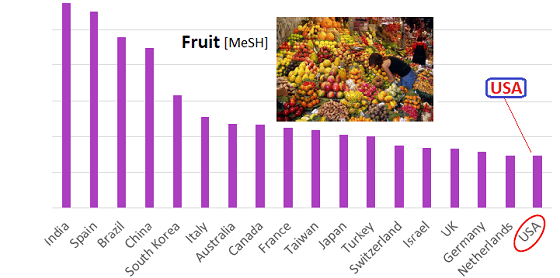

US Lags Behind The World In Plant-Based Food Research

Many other countries spend a much larger proportion of their research time and resources on plant-based foods than the United States does. By Xiaomei Gu, Eric Rumsey and Janna Lawrence In our explorations of plant-base foods (PBFs) in PubMed, it’s often striking that there are many excellent articles from non-US countries. So we did aContinue reading “US Lags Behind The World In Plant-Based Food Research”

Nuts as a Healthy Food: How to Search in PubMed

By Eric Rumsey, Janna Lawrence and Xiaomei Gu This article is based on a poster presented at the Medical Library Association annual meeting, Toronto, May 2016. Introduction Searching for nuts as food is difficult. As with most plant-based foods, MeSH terms for specific types of nuts are in the Plants explosion instead of in theContinue reading “Nuts as a Healthy Food: How to Search in PubMed”

Searching Nutrition In PubMed & Embase: The Winner Is…

By Eric Rumsey and Janna Lawrence As we’ve discussed, the big problem in searching for food-diet-nutrition subjects in PubMed is that the subjects are not together in a convenient bundle, as most subject groupings are in PubMed. To get a list of articles that includes food, diet and nutrition, it’s necessary to search each ofContinue reading “Searching Nutrition In PubMed & Embase: The Winner Is…”

Plant-Based Foods – An Inclusive PubMed Search

This article has been superseded by the following: Plant-Based Foods – An Inclusive PubMed Search – Revised 2016 ********************** By Eric Rumsey and Janna Lawrence In our earlier article on searching for plant-based foods (PBF) in PubMed, we suggested that a quick way to search the subject is to combine MeSH plant-related explosions AND ourContinue reading “Plant-Based Foods – An Inclusive PubMed Search”

PubMed Food Problem: Cranberry & Cranberries

By Eric Rumsey and Janna Lawrence Part of the problem in searching for food in PubMed is that it’s often the case that there’s a fuzzy border between between food and medicine. A food that is enjoyed for its taste and general nutritional benefits may have properties that make it therapeutic for specific health conditions.Continue reading “PubMed Food Problem: Cranberry & Cranberries”

Is Chocolate A Food? A Problem In PubMed

By Eric Rumsey and Janna Lawrence [Check out additional articles on PubMed & Plant-Based Foods] As we’ve written, searching for food-related subjects in PubMed is difficult because of the way the MeSH system is organized. Plant-based foods are especially difficult because in most cases they are treated mainly as plants rather than food. One result of treating plant-basedContinue reading “Is Chocolate A Food? A Problem In PubMed”