BLANCO, MANUEL (1779–1845). Flora de filipinas. Printed in Manila at the Santo Tomas press, 1837. 21 cm tall.

Manuel María Blanco Ramos was born on Nov. 24, 1779, in Navianos de Alba, a small village in the province of Zamora, Spain. Blanco grew up in Spain, influenced by King Charles III’s commitment to humanism and scientific progress. Despite the turbulence of the 19th century, Blanco emerged as a prodigious figure driven by a desire to serve his parishioners and explore the natural world.

At the age of 10, Blanco entered the College-Seminary in Valladolid, where he studied Latin and philosophy. His thirst for knowledge extended beyond theology; he immersed himself in various scientific disciplines, including chemistry, physics, natural history, mathematics, geography, and astronomy.

After completing his Augustinian training in 1804, Blanco left for the Philippines. Arriving in Manila in 1805, the local Catholic parish assigned him to a monastery in the town of Angat in the province of Bulacan. His primary task was to learn the Tagalog language under the guidance of Brother Joaquín Calvo, who shared Blanco’s passion for plants.

In 1822, he translated Tissot’s Treatise on Domestic Medicine from French to Tagalog. His goal was to incorporate locally available remedies, bypassing those inaccessible to the indigenous population. Given the abundance of local vegetation, he focused on indigenous plants with healing properties.

Blanco meticulously observed the country’s vegetation. He collected plant specimens, took notes, and documented his findings. He lacked formal training as a professional botanist and had no mentors or herbaria for reference. Armed only with Carl Linnaeus’s System Vegetabilium and later Jussieu’s Genera Plantarum, he embarked on a quest to catalog every plant in the Philippines.

His work culminated in the monumental work Flora de Filipinas, según el sistema sexual de Linneo [Flora of the Philippines according to Linnaeus’s system]. This comprehensive work cataloged over 900 plant species, providing valuable insights into Philippine botany.

Father Blanco included common names in Tagalog, Bicol, Visayan, Ilocano, and Pampango alongside scientific nomenclature. Observations included medicinal and practical applications.

Although initially reluctant to publish his work, his fellow friars eventually convinced him that his book would significantly contribute to the scientific understanding of the Philippines. The book proved very popular and Blanco soon started work on a slightly expanded and improved second edition. Unfortunately, he would not finish the book before his death.

Blanco spent the final years of his life in poor health due to a prolonged bout of dysentery. He died on April 1, 1845, at the age of 66.

He had worked diligently on his expanded and corrected second edition, which was nearly complete. His fellow friars finished the book and printed it later that year.

Although Blanco’s herbarium collection no longer exists, Flora de Filipinas remains a testament to his passion for botany and for providing useful medical information to the people of the Philippines.

The John Martin Rare Book Room’s copy of Flora is covered in limp vellum, with the title handwritten on the spine. It is, in modern parlance, chonky—it stands only 21 centimeters tall but is almost 900 pages long! Most of the paper is good quality and sturdy, and although it appears the book may have been resewn and the pages possibly washed, the cover is contemporary with the printed text.

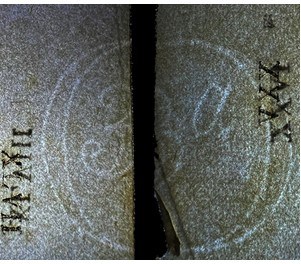

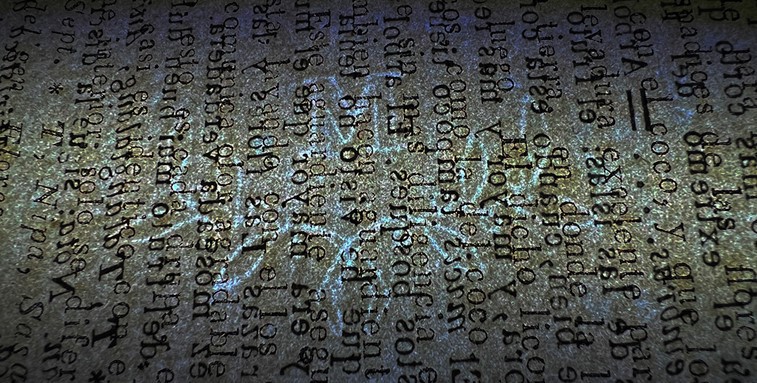

The pages also contain many watermarks possibly from as many as nine separate papermakers. Identifying watermarks can be a bit tricky. Some are well-documented and we know exactly who they belong to. Thanks to the Filigranas Hispánicas watermark database and other watermark databases, I could identify the following watermark as Roman Romani, an 18th-century family of papermakers in Málaga, Spain.

I got lucky, though, because the Romani’s signed their work with their full name. Many watermarks are not so straightforward. The heart you see below is cataloged in a few different places, but I could not find who it belongs to.

The tall mark in gold below is a good example of a variation on a theme—three circles, initials for the papermaker, and topped by the Genoese coat of arms (two griffins on either side of a cross topped by a crown). The Republic of Genoa in Italy was a major European hub for papermaking and mercantile shipping, so there are a lot of examples of this style of watermark.

Unfortunately, I haven’t yet identified which mill the initials SP correspond to. Same with the M with the vine beneath it and the 3a and IB watermarks. But the search is the fun part!

Contact me to take a look at this book: damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154.