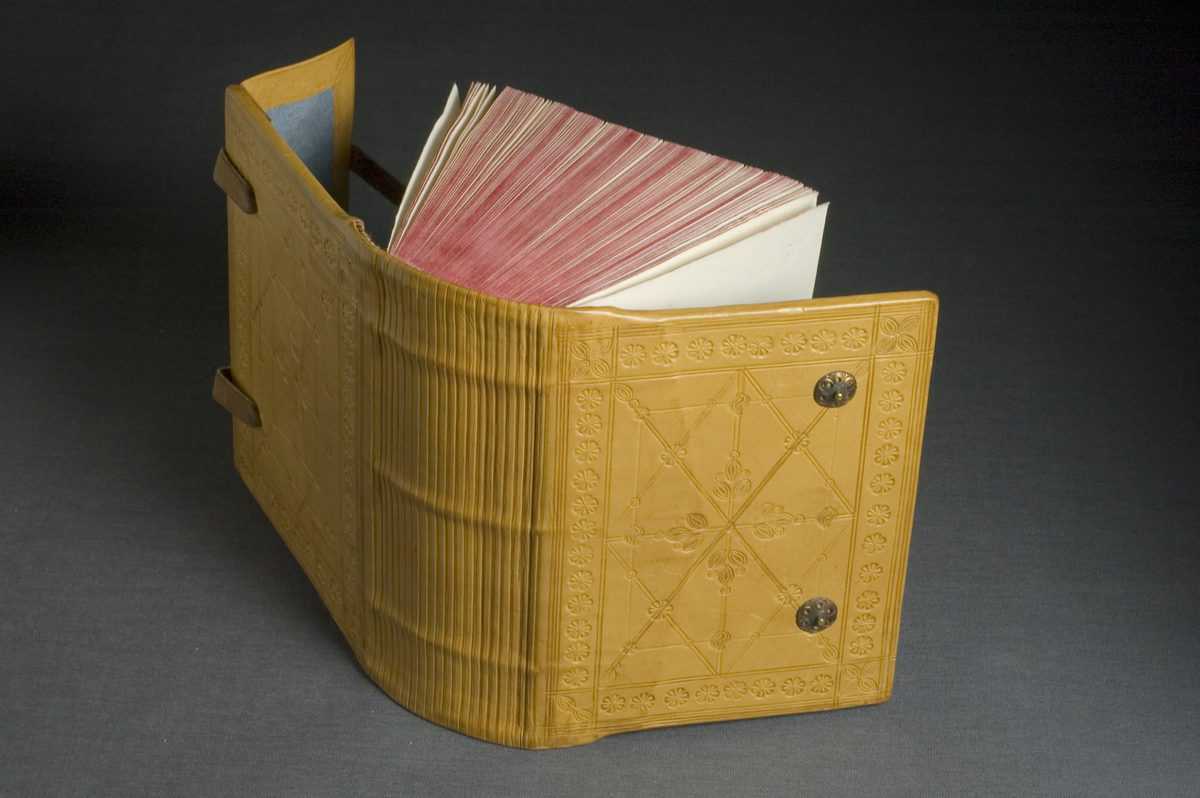

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Natasha Otteson from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0001) 17th Century Armenian Bookbinding Traditions By Natasha Otteson The University of Iowa Libraries has aContinue reading “17th Century Armenian Bookbinding Traditions”

Category Archives: From the Classroom

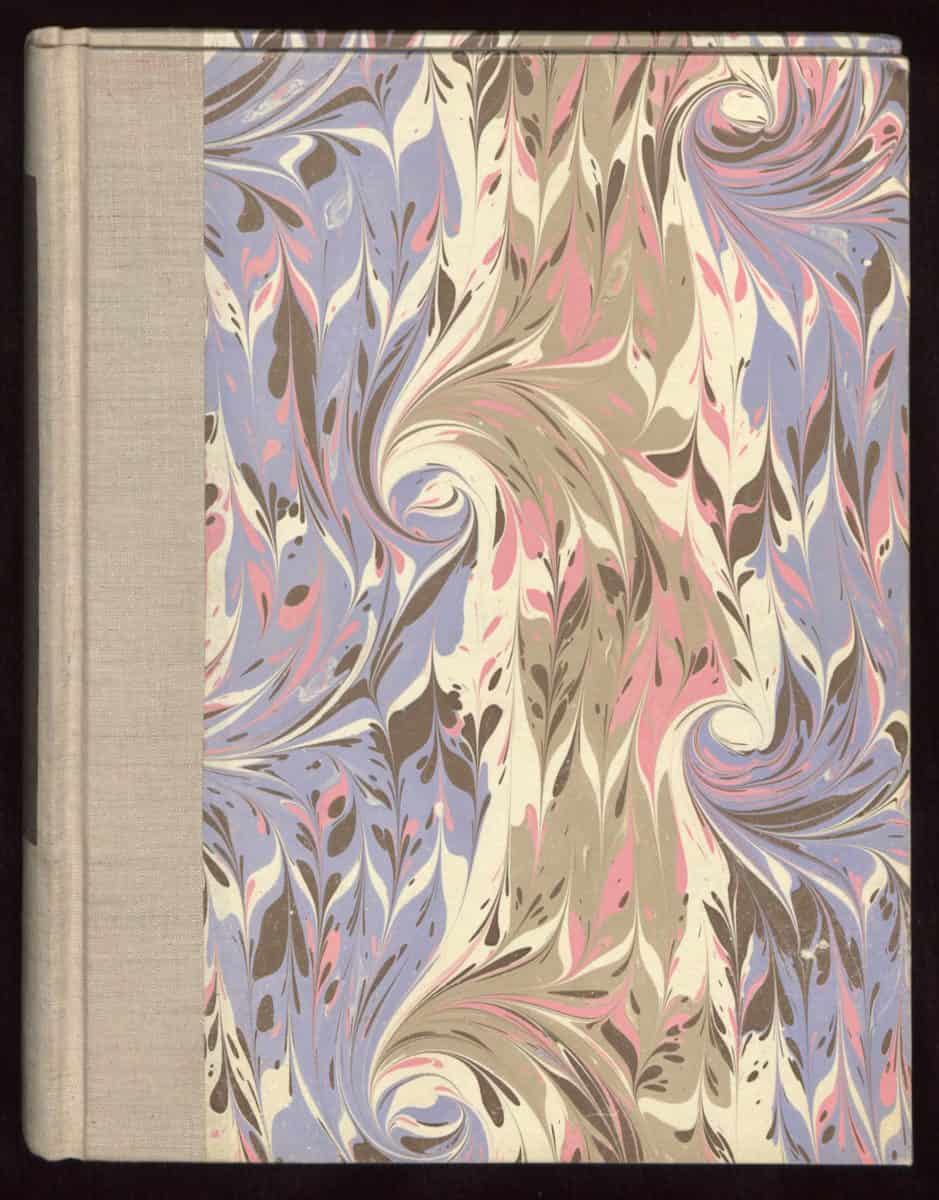

Cookbooks, Citation, and Community

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Breanna Himschoot from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0001) Cookbooks, Citation, and Community By Breanna Himschoot Under its bright lavender marbled binding, this handwrittenContinue reading “Cookbooks, Citation, and Community”

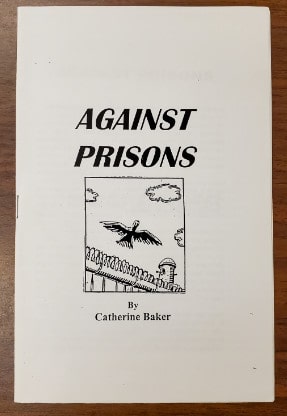

From the Classroom- Steal This Zine!

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Jacob Roosa from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0EXW) Steal This Zine! By Jacob Roosa No, really, steal this zine. Examples of anti-copyright noticesContinue reading “From the Classroom- Steal This Zine!”

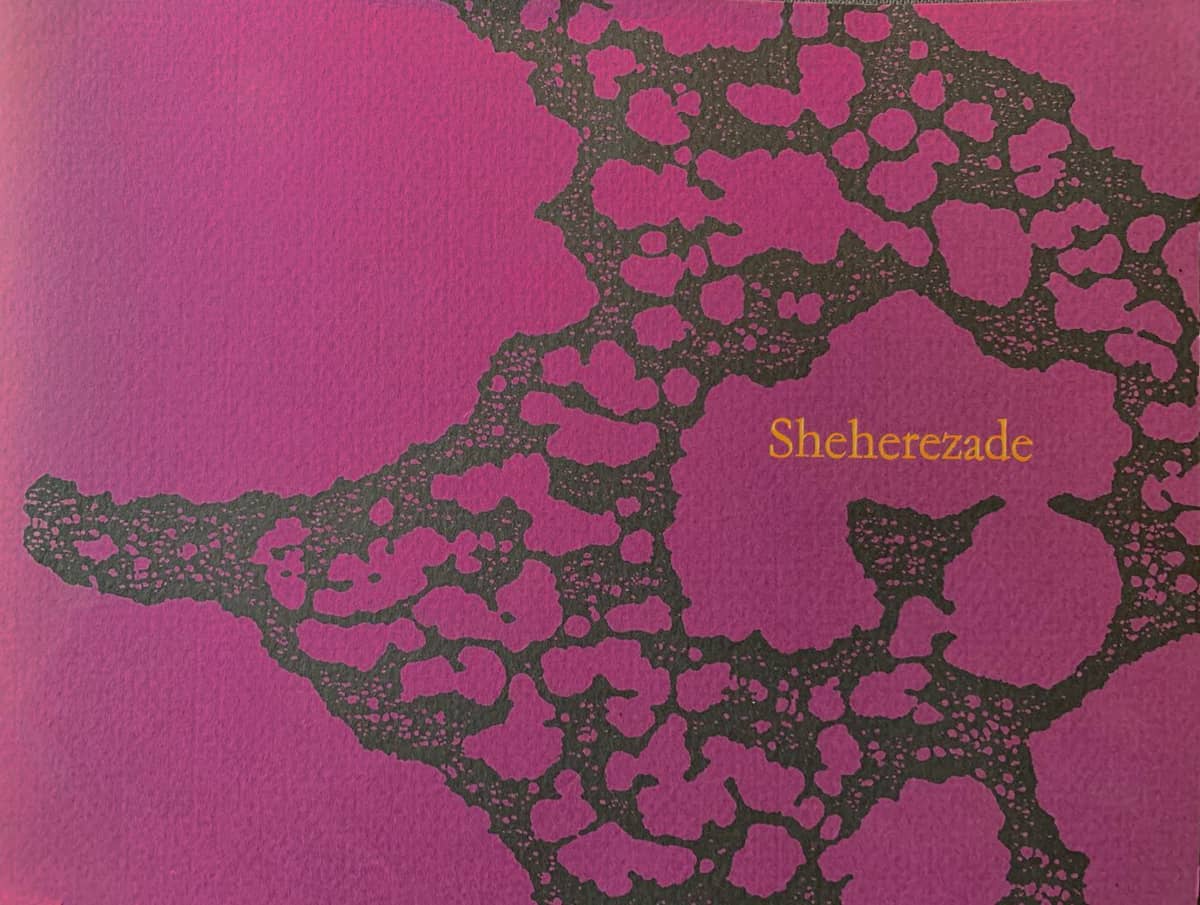

From the Classroom- Sheherezade: a flip book

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Leslie Hankins from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0EXW) Sheherezade: a flip book By Leslie Hankins The bold imperial purple cover with the title,Continue reading “From the Classroom- Sheherezade: a flip book”

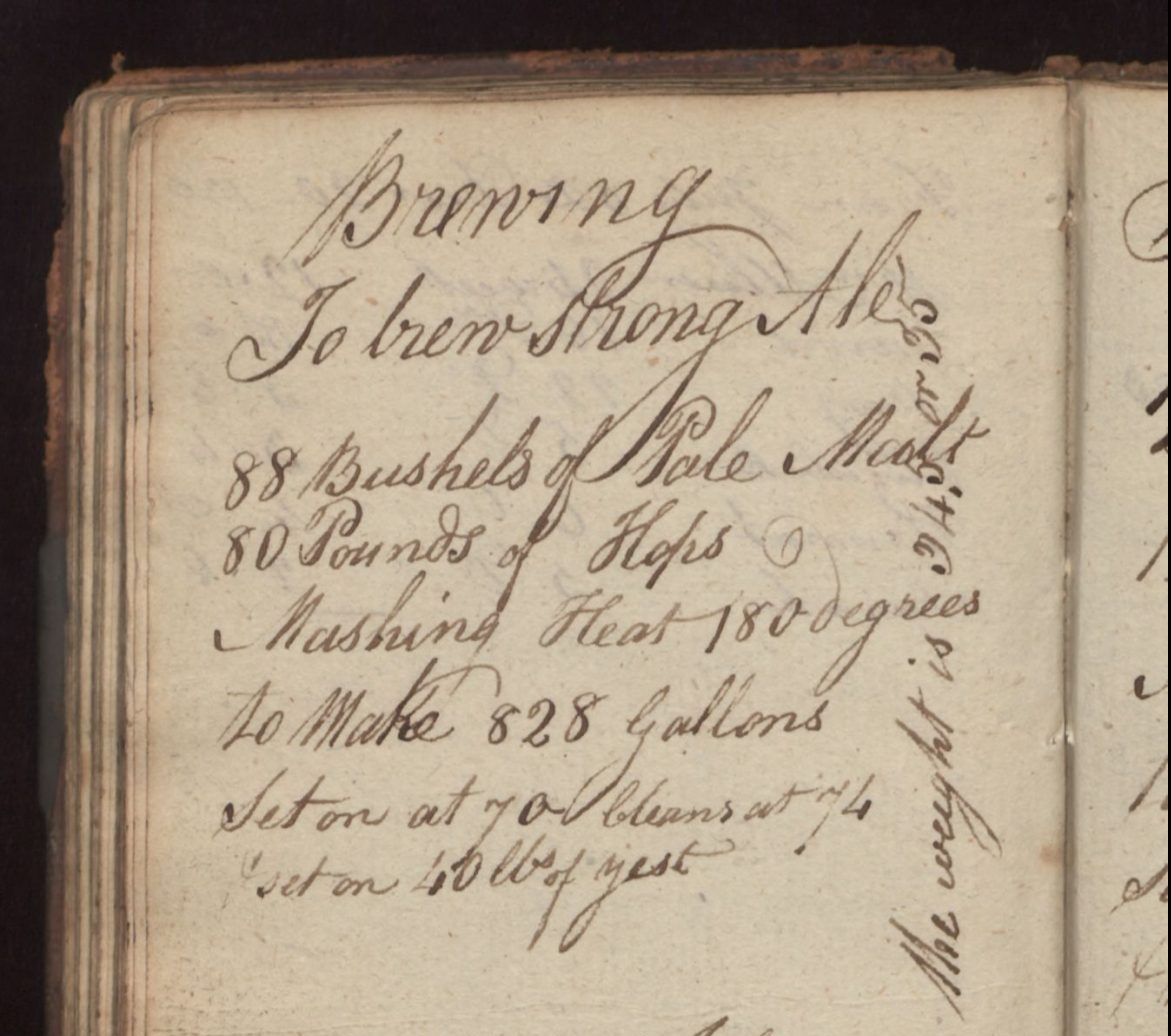

From the Classroom–Business, Beer, and the Bible: The Case of the Maude’s Commonplace Books

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Elizabeth McKay from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0EXW) AMERICAN COOKERY MANUSCRIPTS: MAUDE, WILLIAM & JOHN. Brewer’s Duties & Commonplace Books (2), Early 19th Century,Continue reading “From the Classroom–Business, Beer, and the Bible: The Case of the Maude’s Commonplace Books”