The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant Matrice Young

Frederick Wayman “Duke” Slater was born in 1898 in Normal, IL to George and Letha Slater. Slater’s first experience playing football came on the streets of the Southside of Chicago, playing pick-up games with the neighborhood kids. During their time playing, Slater discovered a love for tackling, while many of the other kids in the neighborhood much preferred carrying the ball. As such, Slater always had a spot as a lineman in the games he played as a child.

When Slater was 13, his father, who was a nationally recognized Black Methodist minister, moved his family to Clinton, IA to become the pastor of the A.M.E. church. When Slater became a freshman at Clinton High School, he told his father he wanted to play football. His father forbade it, feeling that football was dangerous.

Slater, however, didn’t really take no for an answer. He secretly joined his high school’s football team during the summer leading into his sophomore year.

Slater’s father discovered his son’s football career when he came home one day and saw his wife, Slater’s stepmom, sewing and repairing a uniform that Slater had inherited. Slater’s father told his son to quit. Instead, Slater went on a hunger strike in protest, which lasted several days. Eventually, his father relented and gave Slater the condition that he be careful when he played, that he did his best to avoid getting hurt. With that in mind, Slater often hid his injuries instead of talking about them.

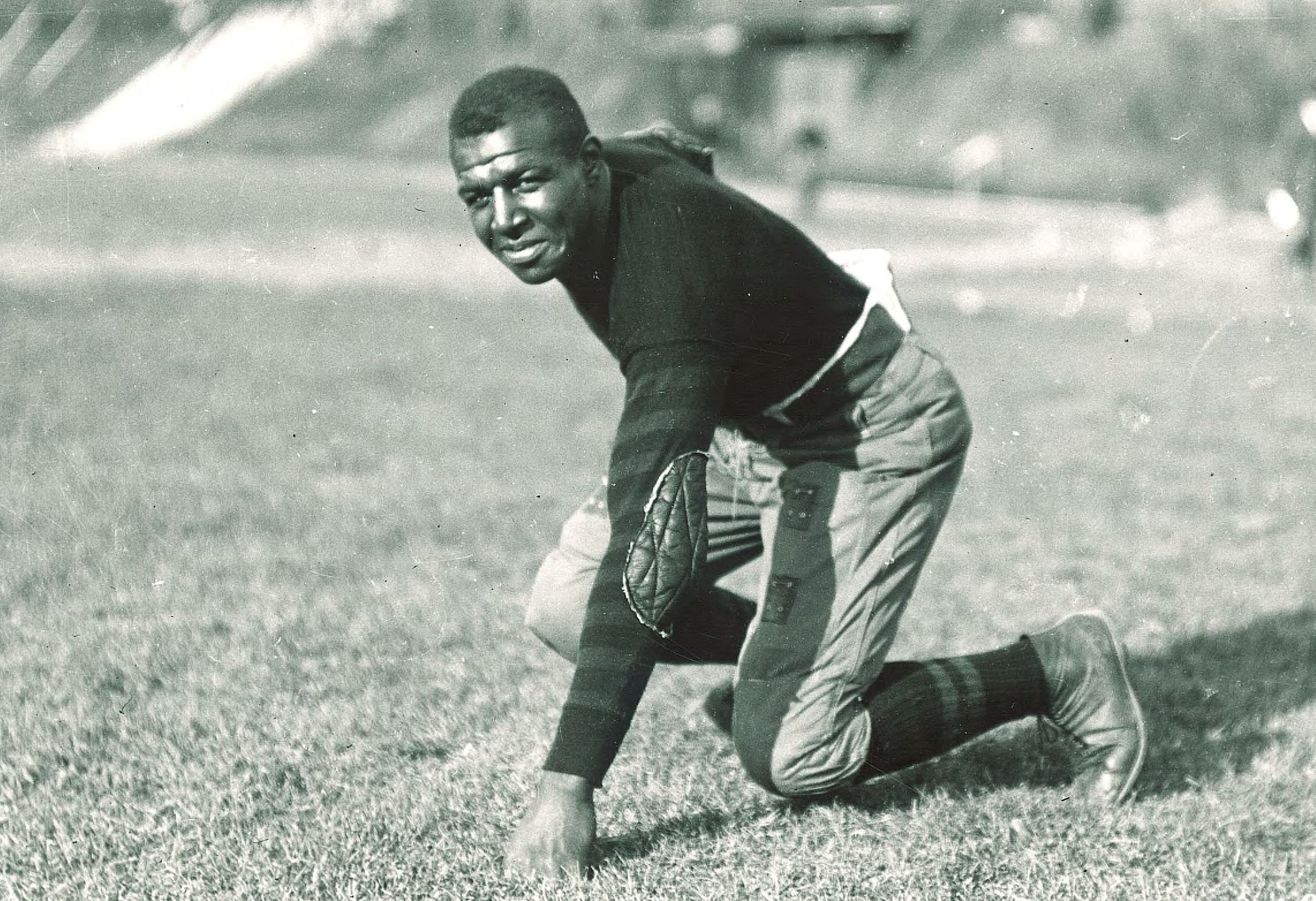

After Slater joined the Clinton Football team in 1913, he was faced with a tough choice: helmet or shoes. During this time, students had to pay for their own football equipment, and that left lower-income and poor families stranded. Slater’s family was no different. He was the oldest of six children, and had to pick between a helmet, or shoes that had to be custom made to fit him. Slater picked the shoes, which, given his 14 ½ FF size, would’ve likely been harder to find, or play without. Though after he’d picked the shoes, Slater went his entire high school and most of his college career playing without a helmet.

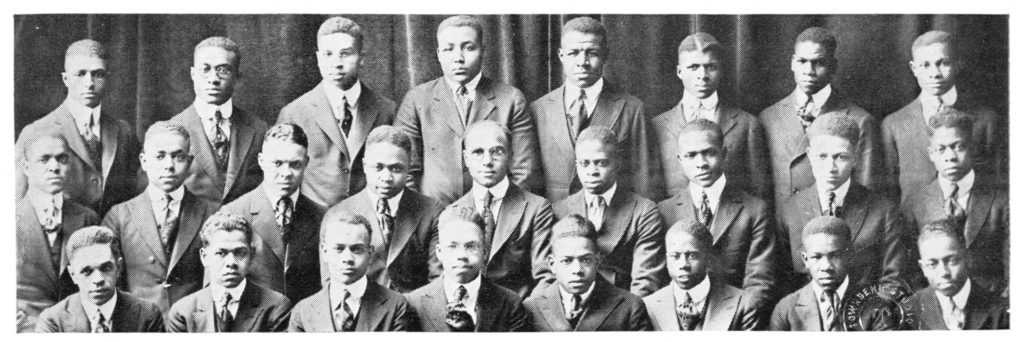

Slater attended the University of Iowa for his undergraduate career and was involved in a variety of extracurriculars including track, an all-Black Fraternity: Kappa Alpha Psi, and of course football.

Slater’s career at University of Iowa held many accomplishments: he was the first Black All-American football player, one of the inaugural class members of the College Football Hall of Fame, and in 1946, he was selected on “an all-time college football All-American team” by a panel of nationwide voters.

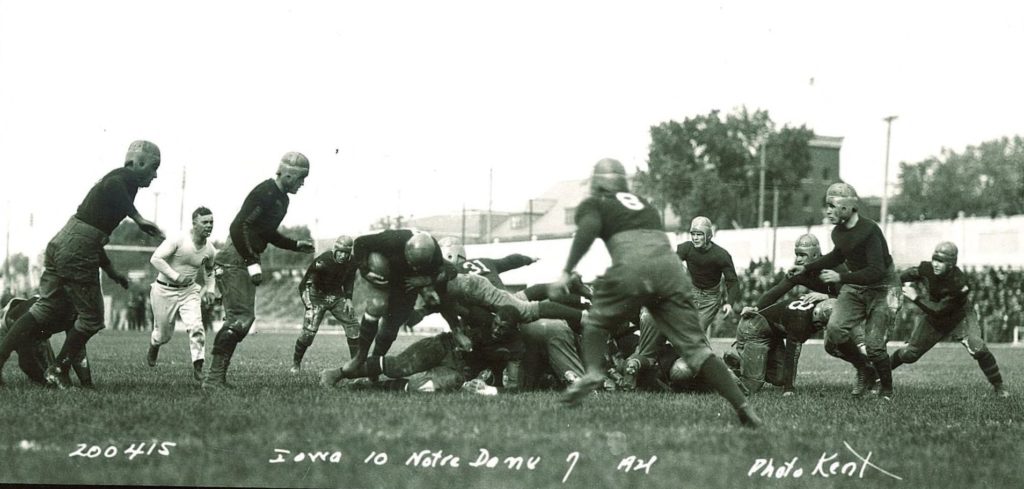

One of his biggest accomplishments on the Hawkeyes football team, however, was his play on the field versus Notre Dame. Hawkeyes ruined Notre Dame’s 20 game win streak, and Slater’s helmetless form is not only featured in the forefront of this famous picture but is also now immortalized as a statue at Kinnick Stadium.

After Iowa, Slater joined the NFL’s Rock Island Independents in 1922, where he became the first African American lineman in the NFL, briefly played for the NFL’s Milwaukee Badgers (only for two games), came back to the Independents, and then after the Independents went bankrupt, Slater played for the Chicago Cardinals. By the late 1920s, the NFL was going to ban Black players, but Slater’s reputation as the best lineman in the game held the NFL at bay. Slater was one of the few African American players in the NFL during the late 1920s, and depending on the year the only African American player on the field. He was also named all-pro from 1923-1930 and was the first NFL lineman to make all-pro teams for seven different seasons. Slater’s presence in the NFL delayed the implementation of the color ban until he retired in 1931.

After his retirement, Slater still took part in sports, however, it was more on the lines of being a social justice advocate for Black Americans. He was the head coach of the Chicago Negro All-Stars in 1933, the Chicago Bombers in 1937, the Chicago Comets in 1939 and the Chicago Panthers in 1940. When the NFL banned Black players in 1934, Slater coached the barnstorming teams that had Black players to fight against the color ban. His fight for representation didn’t end with sports either, it also transferred into his law career.

While playing for the NFL, Slater attended the University of Iowa for law school. He received his degree and passed the bar exam in 1928, then began his professional law career while playing for the Chicago Cardinals.

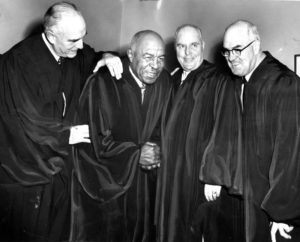

Slater started his practice on the South Side of Chicago and became an assistant district attorney and the assistant Illinois commerce commissioner. In 1948, Slater became Chicago’s second Black-American elected judge on the Cook County Municipal Court. In another great feat, in 1960, Slater was the first Black judge to be appointed to Chicago Superior Court, which was the highest court in the city during that time. In 1964, Slater left the Superior Court to help the newly created Circuit Court of Cook County. Slater’s career as a judge, while not as largely documented, was a push against stereotypes against Black individuals, particularly Black athletes. His almost two-decade career as a respected judge on the South Side of Chicago proved that not only could Black athletes succeed, but that they weren’t unintelligent as well.

In 1966, Judge Slater passed away from stomach cancer. He was buried at Mt. Glenwood Memorial Gardens in Greenwood IL, a historic cemetery where many prominent Black Americans were buried. To honor him, in 1972, the University of Iowa renamed their newest residency hall on campus from Rienow II to Slater Hall. Still, Slater’s story and accomplishments are swept away in the tide of history, and so University of Iowa honored him again in 2019 by erecting a relief of the famous picture from the Notre Dame game, placing it at the North End Zone of Kinnick Stadium. In early 2021, the playing field at the Kinnick Stadium was named Duke Slater Field.

Duke Slater was not just a football star, he was an advocate for Black Americans, a loving brother and uncle, a respected and highly regarded judge, and according to his niece, Hoskin Wilkins, “A man of character.”

You can learn more about Judge Slater’s football career at the University of Iowa through the book Slater of Iowa in our University Archives, and more on his life afterwards through his vertical file.

Sources:

- Duke Slater: Groundbreaker and Champion from the Iowa Facilities Management website

- About Duke Slater from the Neal Rozendaal blog.

- Duke Slater, pioneer Chicago Cardinal and city judge, deserves Hall of Fame spot from the Chicago Tribune

- Hawkeye Throwbacks Honoring 1921-22 Football Team: Duke Slater on BlackHeartGoldPants, a SBNation community blog.

- Iowa Names Duke Slater Field at Kinnick Stadium from HawkeyeSports website.

- Hall of Fame 2021: ‘One-man line’ Duke Slater dominated on field, broke racial barriers from the Canton Repository newspaper site.

- Duke Slater, Athlete, and Judge born from the AAREG (African American Registry) website.