Over the next year, we’ll be celebrating the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the United States. Already, we’re marking important dates. 100 years ago on June 4th, Congress passed the 19th amendment, and July 2nd was the 100th anniversary of Iowa’s becoming the tenth state to ratify it. Women’s suffrage is one of the United States’ greatest and perhaps best remembered women’s movements. In the Iowa Women’s Archives latest reading room exhibit, we tip our “pussy hats” to the many times since suffrage that women in Iowa have protested for rights and respect as equal citizens of their county.

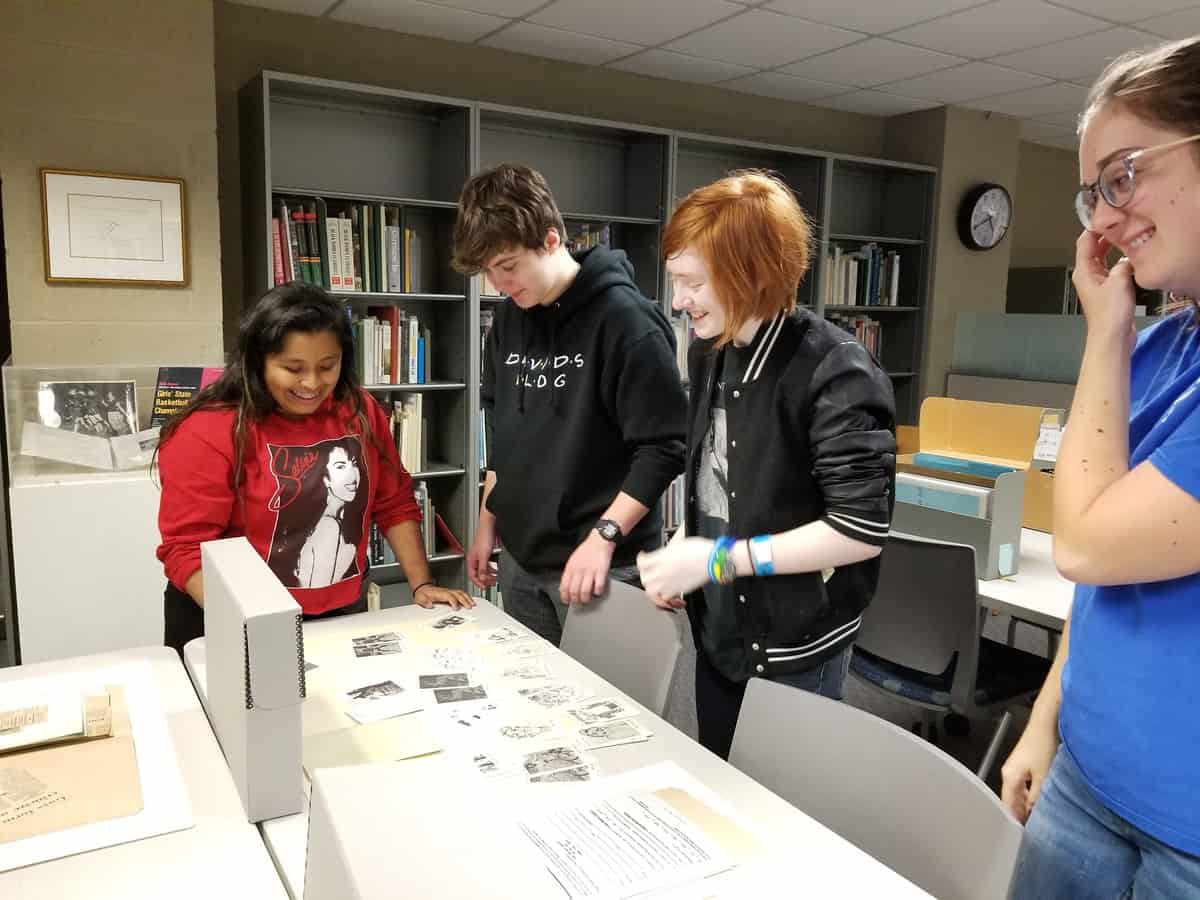

The small exhibit draws from four IWA collections, touches on several women’s rights issues and protests and opens the doors to many IWA collections!

You may recognize the pink “pussy hat” from the 2017 Women’s March. Women knitted these pink (or sometimes purple) hats to wear to the January protest during President Trump’s inauguration. Some estimates say that 4.1 million women participated in Women’s Marches around the world, including sister marches in Iowa! This is just one of four examples of pussy hats preserved at the Iowa Women’s Archives along with photographs and protest signs of women who marched in Iowa City, Des Moines, and Washington D.C.

Right below the hat is a Daily Iowan article by Iowa City activist, Barbara Davidson, about the 1979 Take Back the Night rally Iowa City. The women who rallied in College Park that night dreamed of a community where women could walk at night safe from fear and from sexual violence. Davidson said, “… women of Iowa City will have a chance to support each other in a move to reclaim the freedom that comes from being unafraid.” Take Back the Night rallies are still held around the country and in Iowa City. You can see more recent examples of Take Back the Night activism in the Miranda Welch papers.

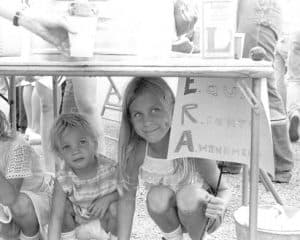

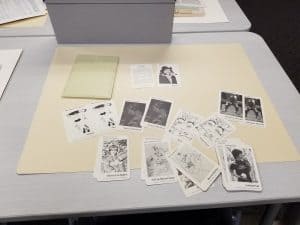

In the back of the case, you can see a large photograph from the National Organization for Women (NOW) Dubuque Chapter records. This particular chapter, founded in 1973, spent a large portion of its efforts on passing the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The ERA states simply that, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” In this photograph, you can see two young Iowans joining the campaign. Although Iowa ratified the ERA in 1972, it has struggled to pass a state ERA. State ERA legislation went to the ballot in 1980 and 1992 and lost both times. You can learn more about these campaigns in the Iowa ERA Coalition records, the Iowa Women Against the Equal Rights Amendment records, and the ERA Iowa 1992 records at the Iowa Women’s Archives.

Finally, the display features a sampling of political buttons from the Ruth Salzmann Becker papers. Becker was a nurse and community activist in Iowa City who was involved in the Johnson County Democratic Women’s Club. Becker’s papers have dozens of political buttons and this selection promotes some well known feminist topics such as the ERA and reproductive rights. For other political buttons, take a look at the Sarah Hanley papers and the Unbuttoning Feminism collection.

Does anything here peak your interest? You can see the display and any of the suggested collections during IWA’s open hours T – F 10 – 12 and 1 – 5.