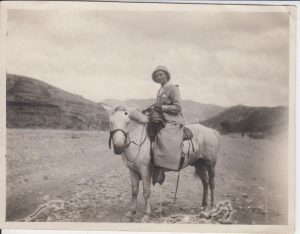

In 1916, a young doctor by the name of Myrtle Hinkhouse stepped onto a ship heading toward China. Years earlier, the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions appointed her to serve in Tengchoufu and, after studying at the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia, she was ready to begin her work. Hinkhouse worked in China for three decades, helping patients, training nurses, and teaching at medical academies before returning to family in West Liberty, Iowa. Her great-niece, Ann, grew up listening to her stories.

I met Ann while working as the director of an ESL program at a local church. She contacted me with the hope of meeting my students from China. She thought they would like to see and even keep some of the items Myrtle brought back from her travels. I set a meeting up with her and about five students, not really thinking anything of it. I assumed, mistakenly, Ann mostly had art or jewelry, maybe a fan or two. I was astonished when she instead pulled out folders of hand-written letters, photographs, and a journal. This wasn’t pieces of art. This was a history collection.

Feeling sick, I watched the students pick out which papers to keep. I knew once the collection was separated, it would be almost worthless. “Ann,” I said, “have you considered donating this to an archive?” She told me she had asked a local historical society, but they weren’t interested. She didn’t think anyone else would be, either. “Ann,” I repeated, “did you ask the University?” The University of Iowa was only a couple blocks away. That fall, I had started the School of Library and Information Science graduate program. Nestled in the same hallway as my classes sat the Iowa Women’s Archives. It seemed if Myrtle’s papers belonged anywhere, it was there, kept together, and accessible to everyone. The challenge was convincing Ann of that.

I’ll spare you the details of how I begged Ann to leave the collection with me, the time spent relocating the items given away in that first meeting, or my devastation upon learning that one student went back to China with most of the photos, even after promising them to me. It was that last event that prompted me to run to IWA, clutching what I did have of the collection. I knew what I had was important; I didn’t know what to do with it, and I was afraid of losing more. But it all worked out. Ann visited IWA later and agreed to donate the collection. I volunteered to process it myself, determined to learn and to see the project through. Around the time I was hired as a student worker, Ann discovered a travel trunk full of Myrtle’s papers. I spent a year piecing through those items, adding the new material into what had already been organized.

Over one hundred years after Myrtle’s departure for China, I’m glad to announce the Hinkhouse collection is finally processed. The finding aid has been published and researchers finally have access to her letters, books, and photographs. As happy as I am, though, the moment is bittersweet. Processors, I think, always feel a connection to the people whose collections they are organizing. It’s hard not to, especially after delving through diaries, letters, childhood essays and recent memoirs. With Myrtle Hinkhouse, though, it was always more than that. She feels like an old friend, one I’ve cared deeply about and worried over, one that brought me Ann’s companionship, and one that pushed me into a new (and happy) path at the IWA during my graduate career. I can only hope she’ll inspire the students and researchers who study her collection as much as she inspired me.

— Rachel Black, IWA Graduate Assistant