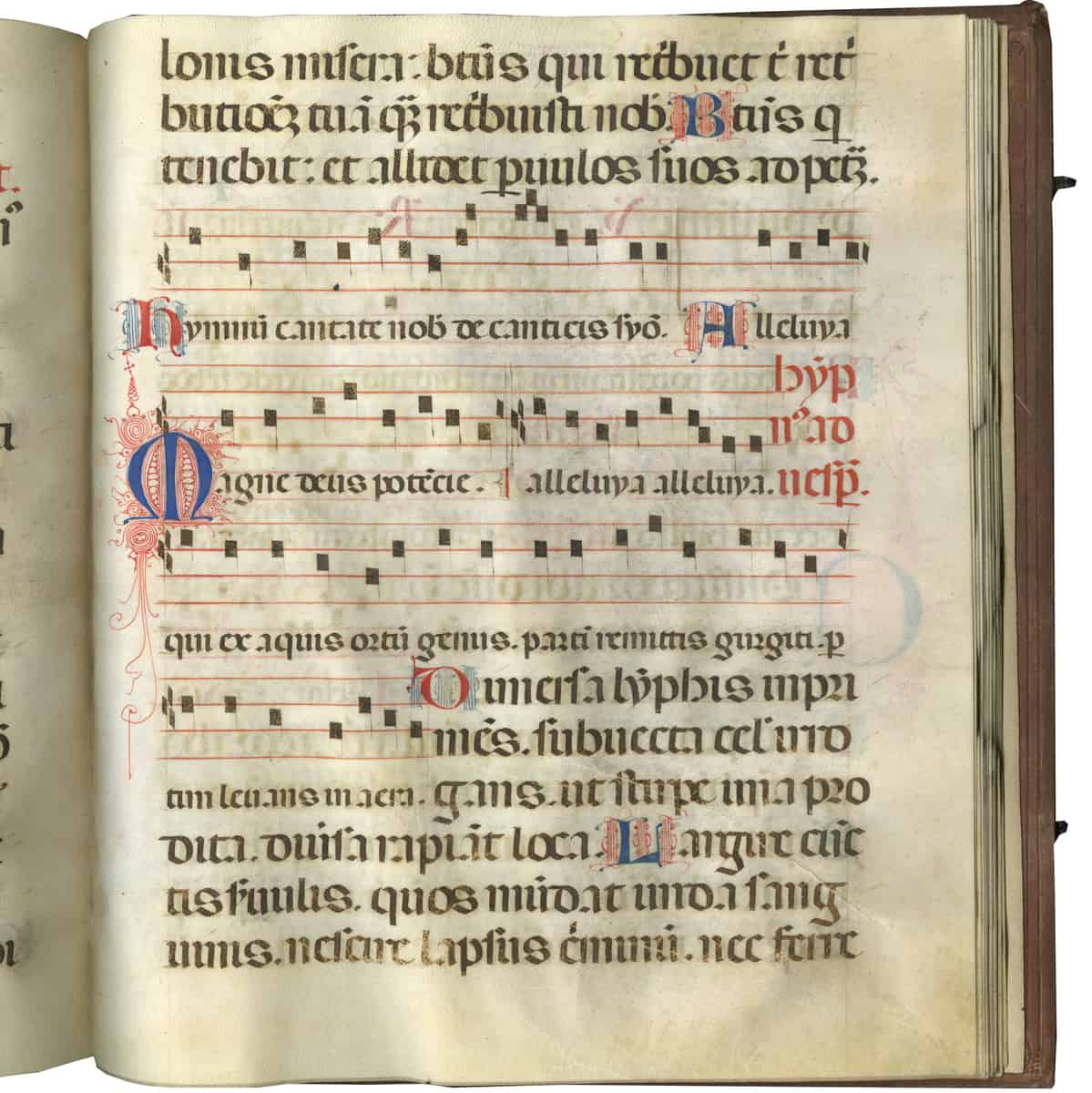

With the new school year beginning, Special Collections has brought in 21 new manuscripts for the fall semester for professors, students, and enthusiasts to enjoy and learn from. These manuscripts are on loan from Les Enluminures, a company with locations in Paris, New York and Chicago. Les Enluminures was created to offer a large andContinue reading “Manuscripts in the Curriculum comes to Special Collections”

Tag Archives: manuscripts

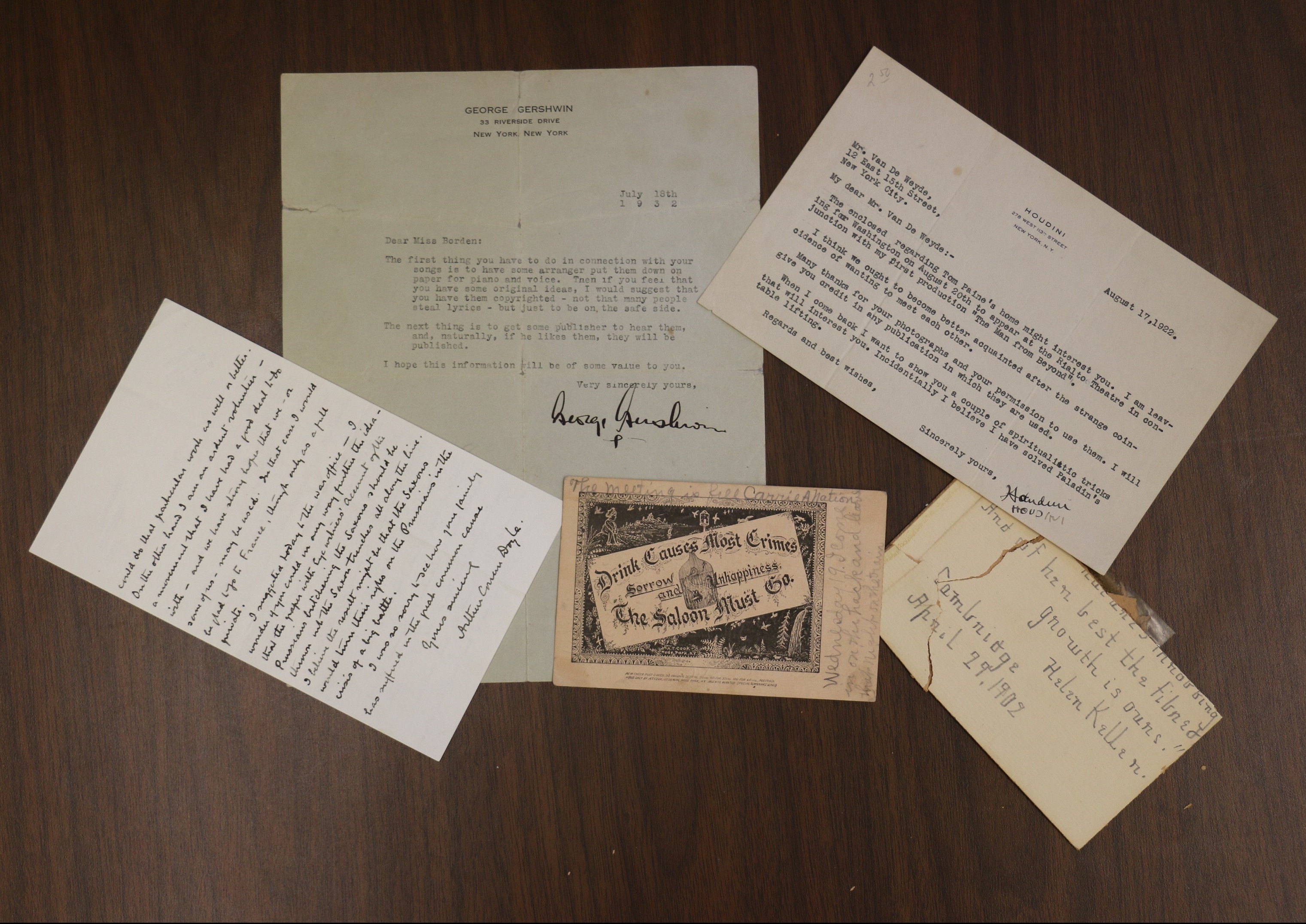

In Plain Sight: Autograph Collections Yield Unrealized Riches

By Jacque Roethler, Manuscripts Processing Coordinator Librarian We recently came across two autograph collections in our stacks from collectors named Charles Alrich and Peggy LeBold which we have combined into one collection. Each one was very sparsely described and their catalog entries did not tell the full story of the riches inside. One was collected by CharlesContinue reading “In Plain Sight: Autograph Collections Yield Unrealized Riches”

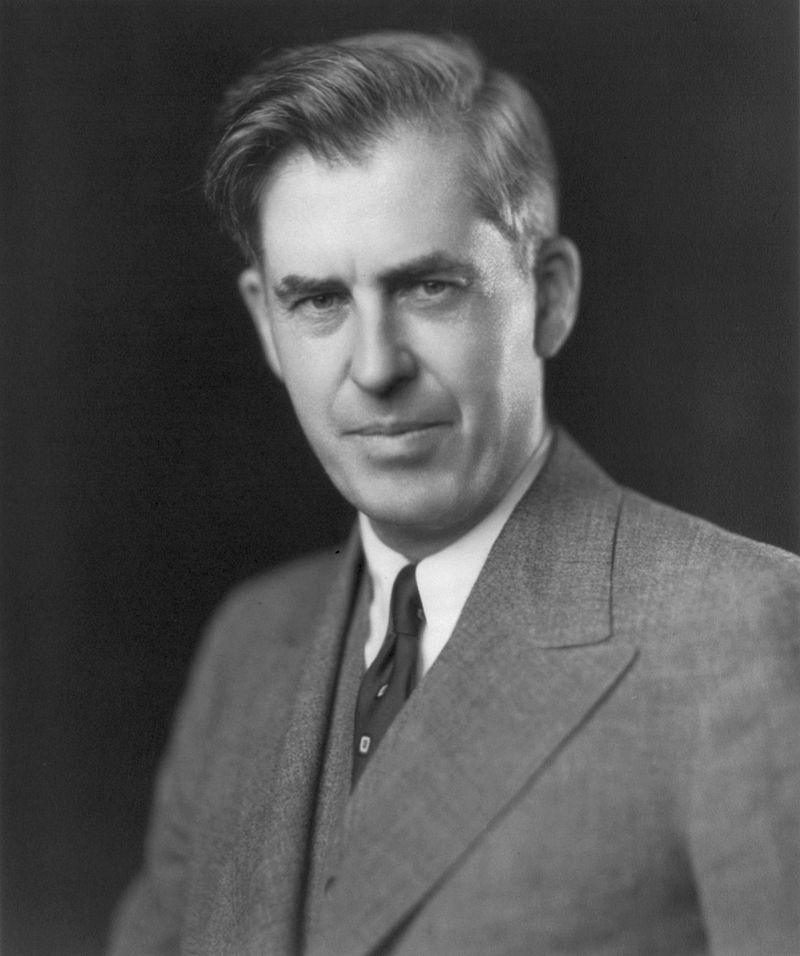

Henry A. Wallace, Advocate for Peace and Unity of the Americas

By Jacque Roethler, Manuscripts Processing Coordinator On the 50th anniversary of his death, we remember Henry Agard Wallace, the 33rd Vice-President of the United States, who was a man well ahead of his times. An idealist who experimented to the point of dilettantism, these avocations destroyed his political career, but he would not back downContinue reading “Henry A. Wallace, Advocate for Peace and Unity of the Americas”

Want to Make Historic Recipes?

Want to make historic recipes? Or how about reading handwriting, converting measurements, recreating historic cooking implements, food photography, or writing and blogging? 300+ years of handwritten cookbooks with thousands of recipes from Chef Louis Szathmary’s culinary collection from Special Collections & University Archives are now online in DIY History, the newest transcription project from theContinue reading “Want to Make Historic Recipes?”

Grand Army of the Republic in Iowa

Today’s post comes from Jacque Roethler on Grand Army of the Republic finds in her recent processing work. Special Collections recently acquired the papers of a law firm in Cedar Rapids, the Bealer/Grimm/Shuttleworth papers. In it were the expected files on cases, insurance, and property, but in a ledger containing E. J. C. Bealer’s 1927Continue reading “Grand Army of the Republic in Iowa”

Mary and Percy Shelley Letter Mentions Frankenstein Rejections – 2 of 3 from Peter Balestrieri

Second in our series of three blog posts from Peter Balestrieri examining our holdings relating to Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus. On August 16, 1817, Mary began writing a letter to Marianne Hunt, Leigh Hunt’s wife. The Hunt’s and the Shelley’s were close friends, their correspondence is extensive, and many of thoseContinue reading “Mary and Percy Shelley Letter Mentions Frankenstein Rejections – 2 of 3 from Peter Balestrieri”

Advertising for “The Collegians,” by Carl Laemmle, Jr.

by Denise Anderson. Fall classes are now in session and the football Homecoming Centennial is upon us, so what better time to examine a felt pennant which advertises “The Collegians,” by Carl Laemmle, Jr. “The Collegians” was a series of 44 two-reel films, in which the same players reprised their characters through four years of a college life fullContinue reading “Advertising for “The Collegians,” by Carl Laemmle, Jr.”