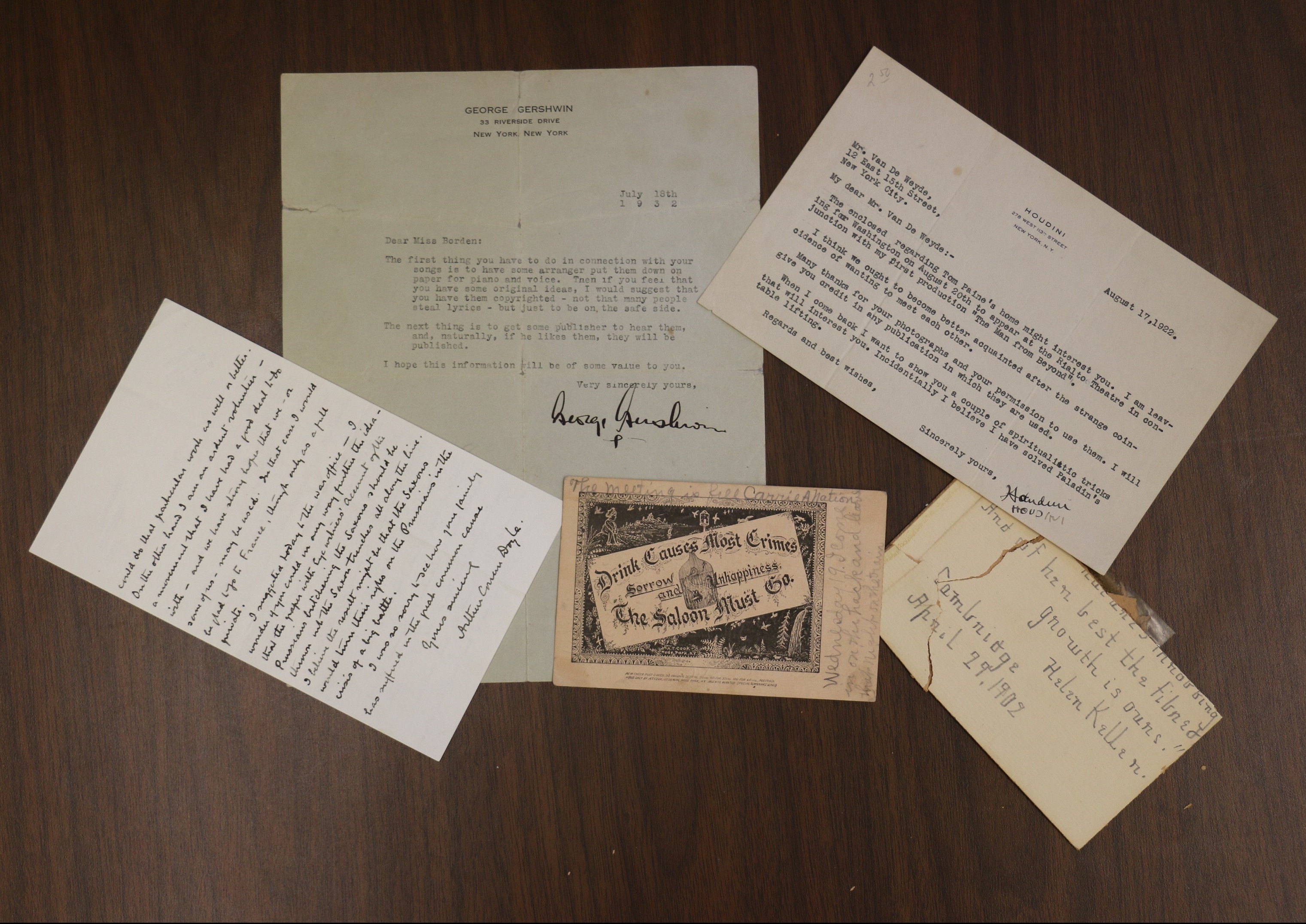

By Jacque Roethler, Manuscripts Processing Coordinator Librarian We recently came across two autograph collections in our stacks from collectors named Charles Alrich and Peggy LeBold which we have combined into one collection. Each one was very sparsely described and their catalog entries did not tell the full story of the riches inside. One was collected by CharlesContinue reading “In Plain Sight: Autograph Collections Yield Unrealized Riches”

Author Archives: Jacque Roethler

Dora Lee and Arthurine: A Story of Two Black Women in 1955-1956

By Jacque Roethler, Manuscripts Processing Coordinator In the firestorm that was the desegregation movement of the nineteen fifties and sixties, the experiences of two women of color makes a nuanced statement about race and its implications. Dora Lee Martin attended the University of Iowa and sixty years ago on December 10, 1955, the seventeen yearContinue reading “Dora Lee and Arthurine: A Story of Two Black Women in 1955-1956”

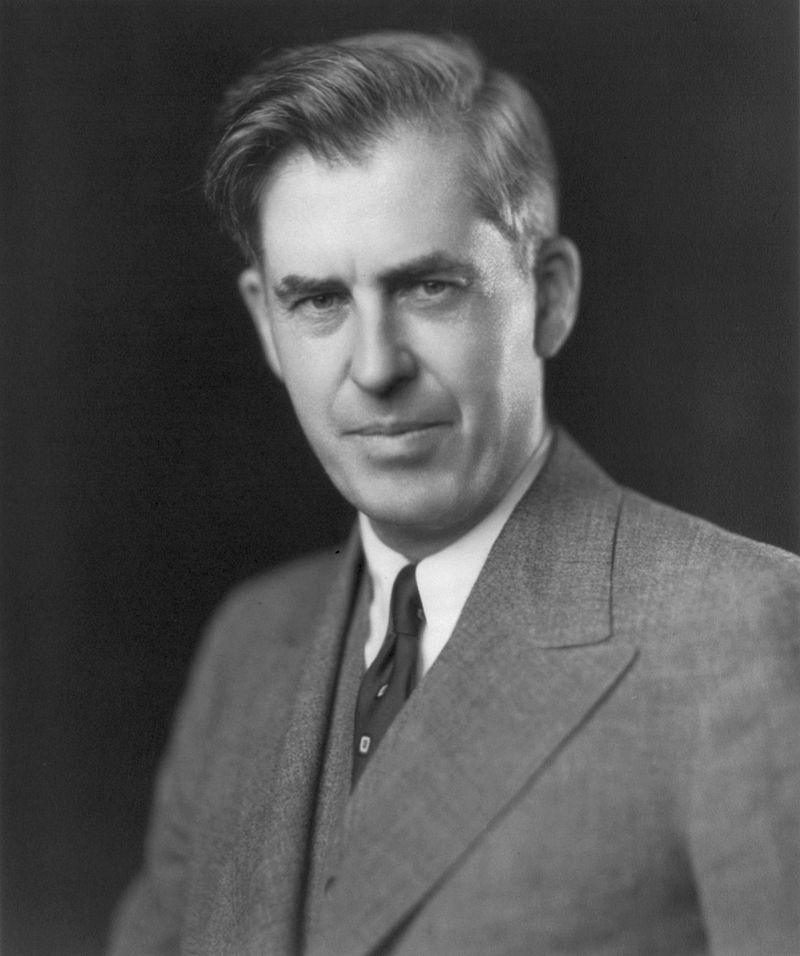

Henry A. Wallace, Advocate for Peace and Unity of the Americas

By Jacque Roethler, Manuscripts Processing Coordinator On the 50th anniversary of his death, we remember Henry Agard Wallace, the 33rd Vice-President of the United States, who was a man well ahead of his times. An idealist who experimented to the point of dilettantism, these avocations destroyed his political career, but he would not back downContinue reading “Henry A. Wallace, Advocate for Peace and Unity of the Americas”

New Acquisition: The Battle Creek System of Health Training

By Jacque Roethler The Battle Creek Sanitarium was opened in 1866 by John Harvey Kellogg and his brother W. K. Kellogg, promoting health through a regimen of dietetics, exercise, hydrotherapy, phototherapy, thermotherapy, electotherapy, mechanotherapy, and enemas. They were joined in this enterprise by C.W. Post. In some areas they were ahead of their time, suchContinue reading “New Acquisition: The Battle Creek System of Health Training”