By Jacque Roethler, Manuscripts Processing Coordinator

In the firestorm that was the desegregation movement of the nineteen fifties and sixties, the experiences of two women of color makes a nuanced statement about race and its implications. Dora Lee Martin attended the University of Iowa and sixty years ago on December 10, 1955, the seventeen year old freshman from Texas was elected “Miss SUI”. Arthurine Lucy was admitted to the University of Alabama but was denied entry in March of 1956 and suffered many abuses. The two experiences are a telling contrast that was remarked upon in several news clippings from the time.

Dora Lee was raised by her grandmother as only child of a partially paralyzed mother. She had an aunt who had no children, so she was surrounded by relatives as the only child of the entire family. She lived in Loving Canadan, a black enclave in the Third Ward of Houston, where the whole area functioned as an extended family. She rarely left this enclave until she went to Jack Yates High School. There she had a hard time at first because she was coming from a two room schoolhouse to a school that served about a thousand students. Also, she says in her oral history recording that she was fat and they called her “doughbelly”. Between the second and third years, however, she lost weight and in the fall of her third year, she became very active in school. In her senior year she was elected “Miss Jack Yates.”

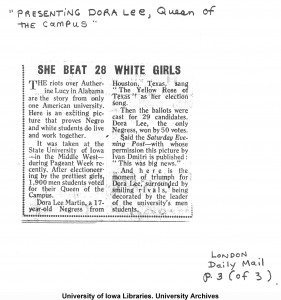

She came to the University of Iowa on a scholarship and within months she had been elected by her dormitory mates to participate in the Miss State University of Iowa 1955 contest. In an oral history she emphasizes that this was not a beauty pageant, but rather a contest involving performance, poise and popularity. She and her dorm mates and her campaign team worked hard, creating a unified presentation (what would be called a brand today) around “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” She was a singer who sang with a band at parties in Iowa City so, as part of her campaign she went to boys’ dormitories and fraternity houses and sang this song for them. They made paper roses to hand out as favors. Martin said that none of the gowns were hers, but her dorm mates would lend her theirs. She had overwhelming support from the Black community. She has said of this experience:

Never before had I been a part of anything where there was such single-mindedness and such dedication – it really felt special to have all these people working together for the same goal. And there was such harmony and unity. It made me appreciate what it meant to be a proud Black American in 1955. What we could accomplish if we all . . . put our efforts together and work for something.” (IWA0331 Oral history transcription, page 19)

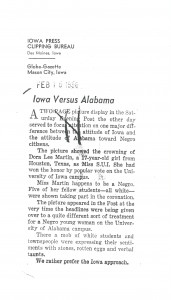

She won the contest by fifty votes. Her election made international news. The University of Iowa Archives has clippings in the vertical files from various towns in Iowa (Oelwein, Humboldt, Mason City, Storm Lake, Sioux City, to mention a few), Kansas City, Des Moines, London, New Delhi. One clipping from Cedar Rapids even states that a woman from Cedar Rapids living in Leopoldville, Belgian Congo reported, “The natives were flocking into the office asking all sorts of questions. Could she speak French, did they think she would adopt them to be a godmother and would she be able to come over here on a trip?” Special Collections even has one publication in Arabic, possibly from Libya.

Contrast this to Authurine Lucy’s experience just a few months later. She was born one of ten children born to farmers in Shiloh, Alabama. She graduate from high school in 1947 and attended Selma University, a school for blacks, and then transferred to Miles College, another all black institution. She wanted to be a technical librarian so she applied to, and was accepted, by the University of Alabama in 1952. That is, she was accepted until school administrators discovered she was black. They then told her state law did not allow her to attend. She sued and it took three years for the case to make its way through the courts, but in 1955 the US Supreme Court ruled that she could attend the University of Alabama. However, she was told that she could not stay in the dormitories or eat in the dining hall. She would have to live in Birmingham and make the 51 mile commute each day to Tuscaloosa and faced expulsion and egg peltings. (See Washington Post article below).

On the third day of classes — time enough for word to get out that a black student was taking classes — upon arriving on campus she was met with an angry crowd of about 500 people. She was whisked into an auditorium. Meanwhile the crowd had grown to some 3000 people, some of them not connected with the University. She was pelted with rotten produce and eggs. At the end of the day she was suspended, supposedly for her own safety. The student body protested the suspension, and she sued the University again. Sometime during the intervening time, her lawyers accused the administration of colluding with the anti-desegregation protesters, which would have dire consequences later. The courts decided in Lucy’s favor and ordered the school to accept her again. They used the accusation of collusion to say that Lucy had slandered the school and thus she could not be accepted. Exhausted from all the court battles, Lucy decided not to sue again.

The two women’s experiences were often compared in the news at the time. Below are three clippings from The Washington Post, The London Daily Mail, and from Mason City, Iowa that make the comparison:

But that’s not the end of these stories. Martin says she never heard anything positive from the administration of the University. This letter from President Hancher may explain some of this silence but Martin says that the events in which previous campus queens had participated were simply silently cancelled. The rules of the pageant were changed so that there was faculty oversight.

Martin has said in her oral history interview,

“. . . my experience had demonstrated that while laws may be different, people are still the same. The only difference being in the South we knew where things stood. We knew what to expect, while in the North people say one thing, but behave in a very different way. And so we were constantly finding ourselves having to figure out where we were wanted and where we weren’t. . . On the campus at the University it was very, very clear in 1955 that institutional racism was still very prevalent at that University.” (Oral History, page 21)

She got on with her education, but left Iowa before she graduated. She married and followed her husband to Chicago, where she attended Roosevelt University, and finally Rutgers, where she received a Master’s in Social Work in 1969. She worked as a social worker in schools.

Lucy also taught as a profession. In 1988, the University of Alabama reversed her suspension and she returned to the University, and in 1992, she finally received a Master’s degree in Education. The University also named an endowed fellowship after her and unveiled a portrait of her in the student union.

These two scenarios played out during roughly the same time period. They look like different ends of the spectrum. But were they really? A closer look at the situation reveals that there’s more to each one than meets the eye.

References come from these collections in Special Collections:

Clippings from Dora Lee Martin Berry’s file in Alumni and Former Students Vertical File in the University of Iowa Archives, RG01.15.01.

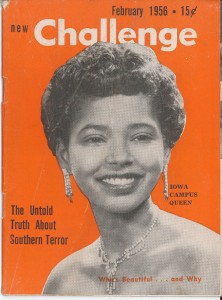

Cover of the New Challenge is in the Progressive Party Papers, 2015 Addendum – The Progressive Party of Massachusetts. MSC0160.

Oral history recording with Dora Lee Martin is part of the Giving Voice to their Memories: Oral Histories of African American Women in Iowa project. IWA0331.