This post is by Archives Assistant Heather Cooper.

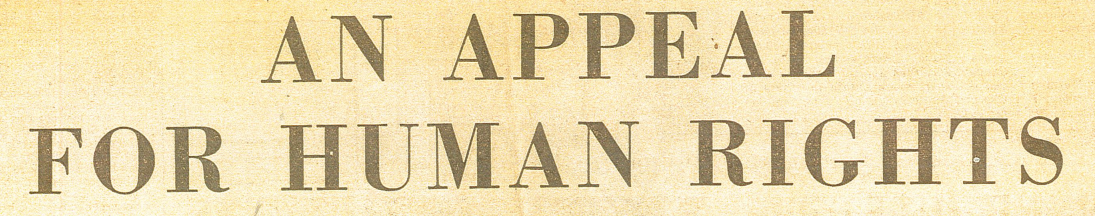

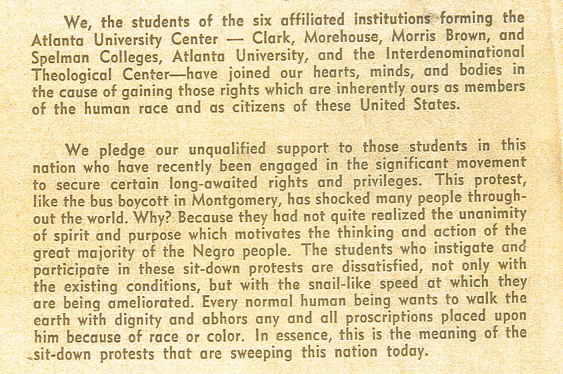

The Iowa Women’s Archives recently received the first installment of a new collection of personal papers from Norma June Wilson Davis. Davis, who later became an administrator at the University of Iowa, was at the forefront of the student civil rights movement in Atlanta, Georgia, in the early 1960s. Born in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1940, Davis recalled that she realized she was different at a young age and resisted expectations that she sit at the back of the bus or drink at the water fountains marked for African Americans’ use when she went into town with her mother. Primarily known as “Norma” prior to her marriage, Wilson moved to Atlanta in 1957 to attend Spelman College and was part of a community of students from several Black colleges and universities who were inspired to organize their own protest movement after the first student sit-ins took place in Greensboro, North Carolina. Wilson was a central figure in what became known as the Atlanta Student Movement (ASM). Announcing their presence on the civil rights stage, representatives took out full-page advertisements in several newspapers, outlining their grievances and objectives. In “An Appeal for Human Rights,” Atlanta students declared that “Today’s youth will not sit by submissively, while being denied all of the rights, privileges, and joys of life. … [W]e plan to use every legal and non-violent means at our disposal to secure full citizenship rights as members of this great Democracy of ours.” As chair of the ASM’s Action Committee, Wilson played a major role in organizing the rallies, picket lines, economic boycotts, and sit-ins that swept Atlanta and the region from 1960 to 1961. The IWA is honored to preserve the papers of N. June Davis in our repository.

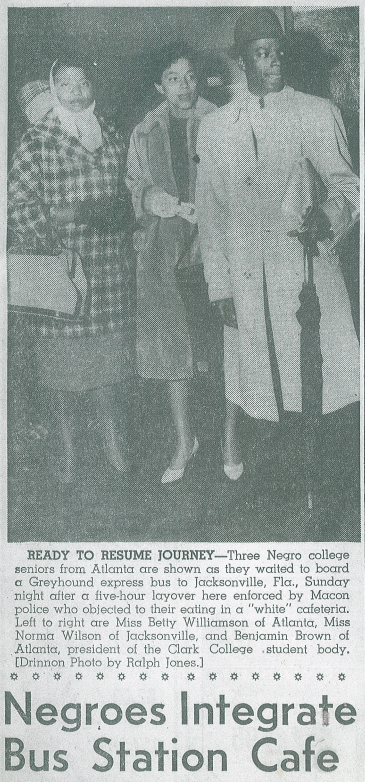

Although her name is far less known than some other civil rights activists, Wilson was a trailblazer in the student movement. Readers are likely familiar with the “Freedom Rides” organized by James Farmer and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) in 1961 – a campaign to challenge segregation in interstate travel and accommodations. Six months before Farmer organized the first so-called “Freedom Rides,” Norma Wilson and other members of the ASM led their own effort to challenge segregation in facilities for interstate travelers. In 1960, Wilson and two other students boarded a Greyhound bus on the Atlanta-to-Jacksonville route. When the bus stopped at a station in Macon, Georgia, they tried to dine in the all-white cafeteria and were subsequently taken into police custody. Davis recalled, “So, we went to the police station and the police chief and I talked and I said, ‘You know we haven’t broken any laws.’ And he said, ‘We don’t serve you.’ And I said, ‘The Supreme Court just said you will.’ So, he left the office and went out, conversed with some people, and found out I was right.” One newspaper noted that it was “the first such integration attempt reported in Macon.” Davis remembered that, after reading about the bus station confrontation in the newspaper, James Farmer called ASM leader Lonnie King and said, “’I like the idea of the rides that you took. I think I’m going to call them Freedom Rides.'” “And that,” Davis said, “is how the Freedom Rides were born.”

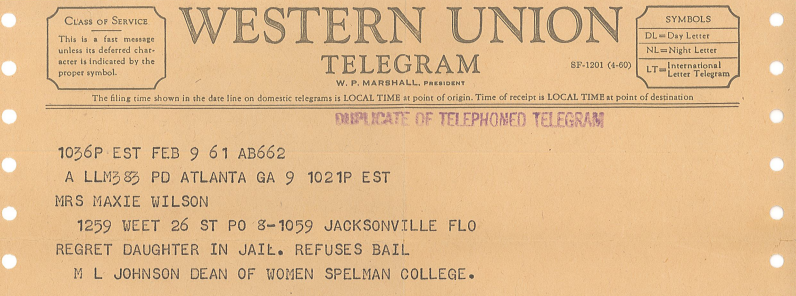

Wilson and her colleagues were not actually arrested in Macon, but arrest was a regular occurrence for students and others who participated in sit-ins and other public demonstrations. The President of Spelman College actually sent letters to parents to inform them that students’ participation in demonstrations “on the desegregation front” could lead to arrest and time in jail. Wilson was sentenced to time in a number of different facilities, including two weeks in a work camp where male prisoners worked on a chain gang and female prisoners picked crops and worked in the kitchen or laundry. Davis recalled, it was “not a safe situation … for the women.” Following one of Wilson’s arrests, the Dean of Women at Spelman telegrammed Wilson’s mother: “REGRET DAUGHTER IN JAIL. REFUSES BAIL.” Wilson and others often refused bail and organized a “jail without bail” campaign in order to pack the jails and “hopefully strain the financial resources of the county.” It was another attempt to use economic pressure to force change. Two years before Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Wilson and other participants in the “jail without bail” program issued a public statement from the Atlanta city jail: “[T]he only way we can achieve our freedom is by being willing to endure and suffer the hardships that are encountered in the achievement of freedom. I only wish that each of you were here to share the darkness of this room, this hard bunk, the smell of the place, and the filth, but yet the light of freedom is slowly slipping in.”

This blog highlights just a few moments in June Davis’s story. This first installment in our new collection of Davis’s personal papers includes fascinating material from her years in Atlanta, including correspondence and a journal from her time in jail, original newspapers and movement publications, and the transcript of an oral history about her work in the ASM. We look forward to receiving and exploring more material that sheds light on Davis’s life and work in Iowa. After moving here with her family in 1968, Davis continued to be a community activist, serving, for example, on an advisory committee that investigated racism in the Iowa City school system. Davis also had a long career at the University of Iowa, where she worked in Residence Services, Finance and University Services, and the Office of Affirmative Action.