The following is written by graduate student and Special Collections student worker Emily Schartz To wrap up American Heart Health Month, we’re remembering University of Iowa professor, cardiologist, and researcher Richard Kerber (1939-2016). If you have noticed the white AED (Automated External Defibrillator) boxes around, you have seen Kerber’s long-lasting impact on our campus andContinue reading “UIowa Hearts Richard Kerber”

Author Archives: Elizabeth Riordan

10 Black Poets to check out in Special Collections & Archives

The following was written by academic outreach coordinator Kathryn Reuter Reading poetry by Black authors is a great way to celebrate Black History Month! We searched through Special Collections and Archives to find materials from Black poets, some who are familiar to us, and some less so. It was tough to limit ourselves to justContinue reading “10 Black Poets to check out in Special Collections & Archives”

Welcome Kate Orazem

We are happy to welcome Kate Orazem as the inaugural Iowa Women’s Archives Women in Politics Archivist. Orazem joined the team at the beginning of October. She received a Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) and Master of Arts in women’s and gender studies from the University of Texas at Austin and a BachelorContinue reading “Welcome Kate Orazem”

Collecting Your Ghost Stories

The following comes from university archivist Sarah Keen Have you heard footsteps where no corporeal being is walking? Have unexplainable events occurred in your building that have no humanly cause? Are there spaces on campus where the spirits of those who have walked this earth before us feel particularly present? If so, the University ArchivesContinue reading “Collecting Your Ghost Stories”

Happy Birthday Lil Picard!

The following is written by academic outreach coordinator Kathryn Reuter. On Tuesday, October 4th, 2022, join the Stanley Museum of Art & the University of Iowa Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives as they celebrate the 123rd birthday of artist Lil Picard! Crafts and cake will be available in the Stanley Museum lobby from 12-2pm, andContinue reading “Happy Birthday Lil Picard!”

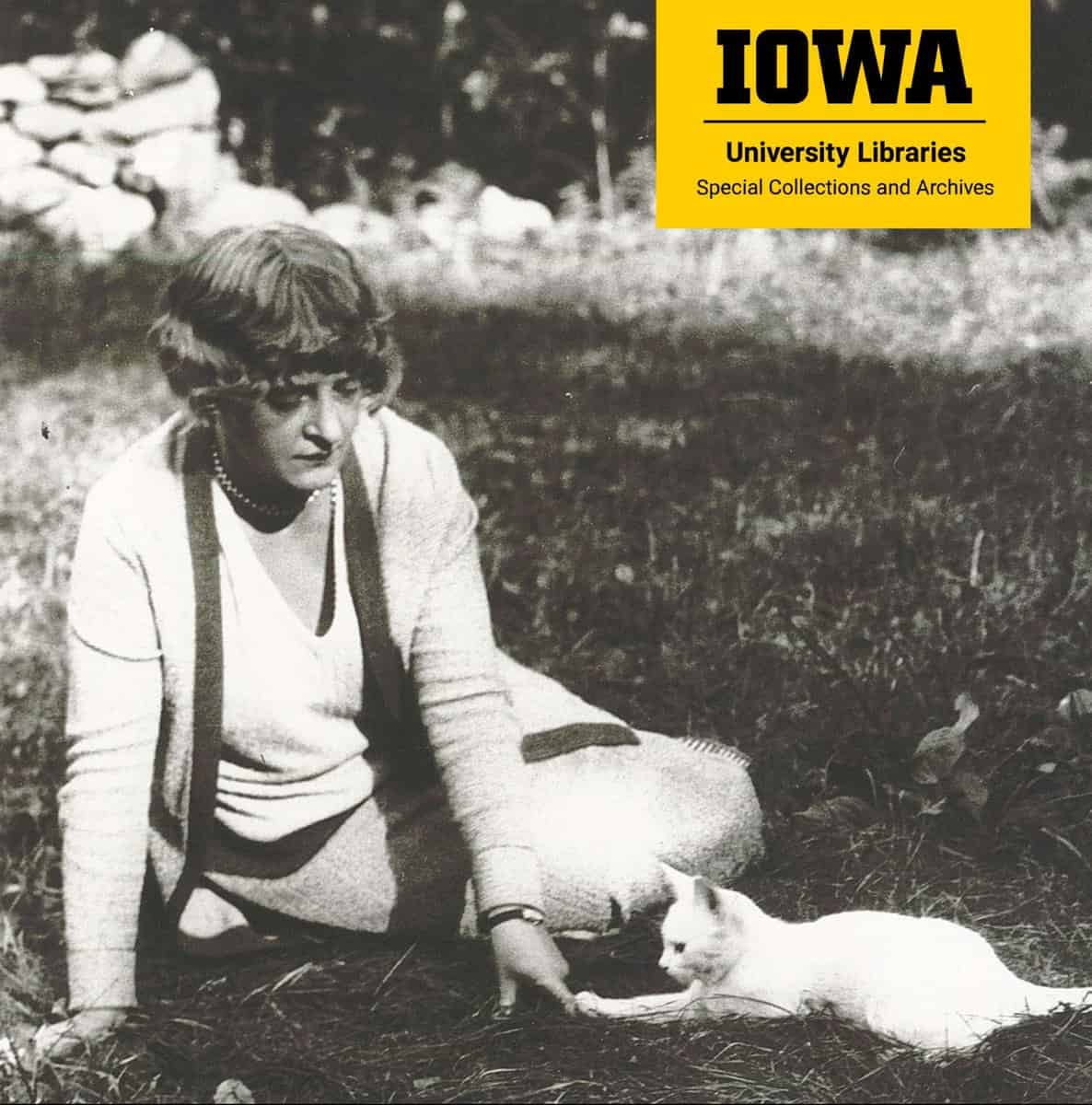

A Tale of Tails: Pets in the Archives

A new exhibit bound to make you feel warm and fuzzy is up in the Special Collections & Archives reading room. Curated by lead outreach and instruction librarian Elizabeth Riordan and academic outreach coordinator Kathryn Reuter, the exhibit A Tale of Tails: Pets in the Archives explores the pets found in Special Collections & Archives,Continue reading “A Tale of Tails: Pets in the Archives”

Welcome Rich Dana

We are pleased to announce Rich Dana as Special Collections and Archives’ Sackner Archive Project coordinator librarian. Rich Dana earned his MFA from the University of Iowa Center for the Book in 2021 and his MA from the School of Library and Information Science in 2020. He has worked as an art mover, art fabricator andContinue reading “Welcome Rich Dana”

Welcome Sarah Keen, our new university archivist

We are pleased to welcome Sarah Keen as our new university archivist in Special Collections & Archives. Sarah joined the Libraries at the start of the fall semester. She comes to Iowa from upstate New York, where she served as Colgate University Libraries’ university archivist and head of Special Collections and University Archives. Previously, sheContinue reading “Welcome Sarah Keen, our new university archivist”

All Women Welcome: Summer 2022 Reading Room Exhibit

The following is written by Rachel Miller-Haughton, former Olson Graduate Research Assistant and curator of All Women Welcome exhibit All Women Welcome: Voices of Activist Iowa Women is the summer 2022 exhibit in the Special Collections Reading Room. The culmination of my time as the 2020-2022 Olson Graduate Research Assistant, the exhibit features images, documents,Continue reading “All Women Welcome: Summer 2022 Reading Room Exhibit”

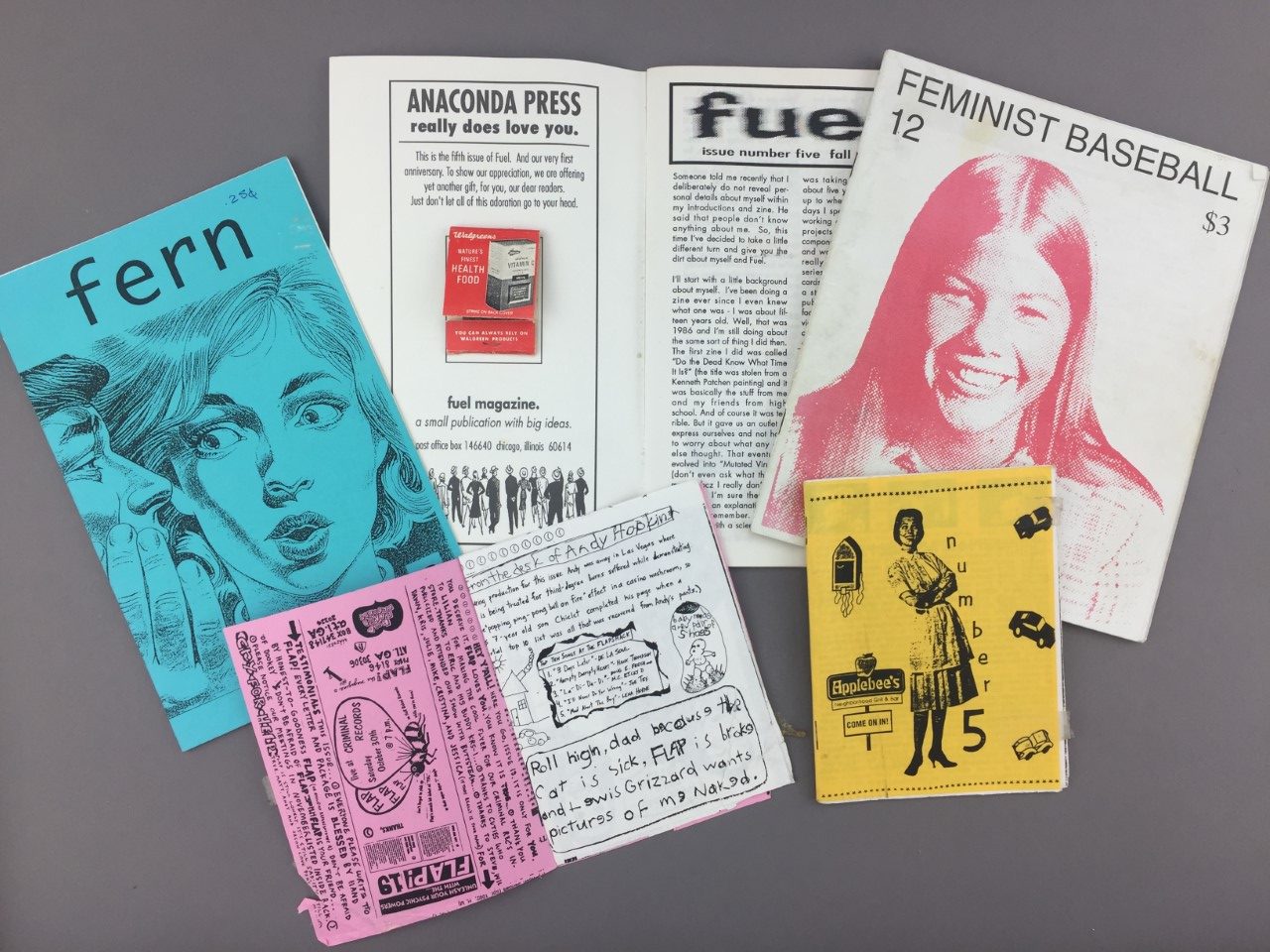

Telling Their Stories: LGBTQ+ Zine History

The following is written by Academic Outreach Coordinator Kathryn Reuter In honor of Pride month, we are highlighting some queer zines in our collections. A zine is a hand-made and self-published pamphlet that can contain writings, collages, comics, illustrations, and other artwork. Zines are made in a variety of styles and cover endless types ofContinue reading “Telling Their Stories: LGBTQ+ Zine History”