The following is written by Erik Henderson, Graduate Assistant for Iowa Women’s Archives

As we have moved into the digital age, the value of handwritten letters has seemingly faded. Archival repositories nationwide are composed of letters because they once encompassed the most influential and sometimes most intimate moments experienced by their authors. Preserving history allows for people in the 21st century to understand the values, norms, and perspectives of life before them. In an era of prompt communication through smartphones and social media, could we imagine what it would be like waiting weeks, or even months, to hear from loved ones?

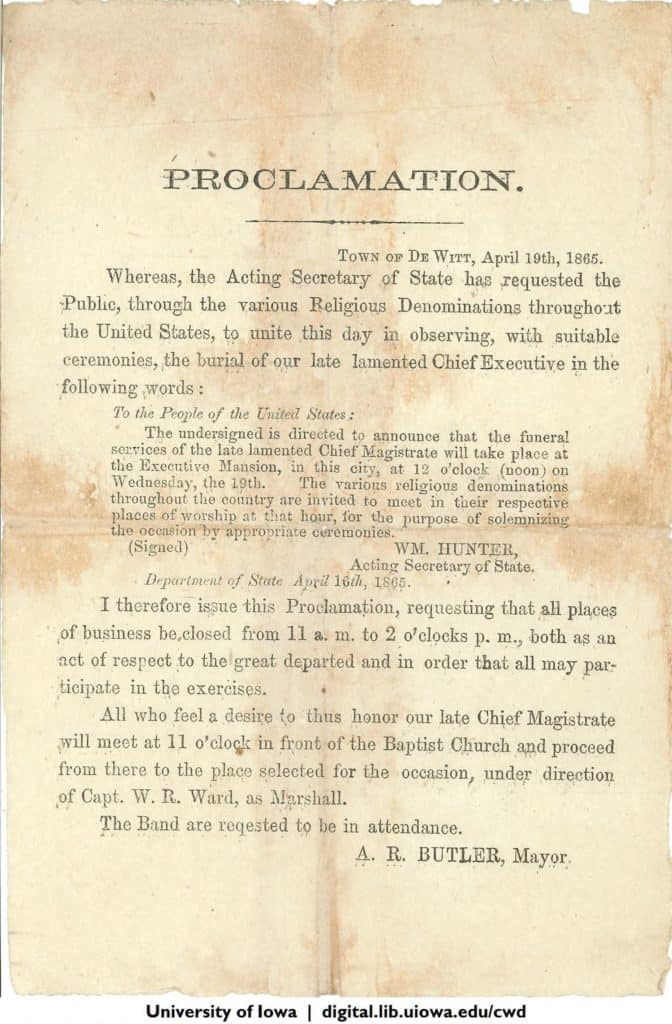

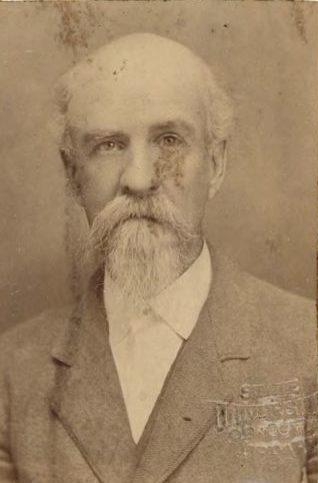

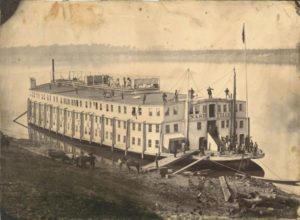

Within the UI Special Collections are the letters of Anson Rood Butler, which transport readers to the Civil War era. Consisting of items dating from 1862 to 1900, this collection is primarily correspondence between Butler and his wife, Harriet Saunders. The letters, all transcribed on Iowa Digital Library and DIY History, describe his time aboard the Nashville, a “floating hospital,” traveling through the south: where he served as the third sergeant of the 26th Iowa Infantry Regiment. The 26th Iowa Infantry, organized in Clinton, Iowa, consisted of Black and White soldiers that mustered in three years of Federal service and were a part of the 3rd brigade, 1st division, XV Corps.

For the Black soldiers of the 26th Iowa Infantry, they battled against their white peers in efforts for them to recognize their worth regardless of their status or the obstacles they faced such as deteriorating weapons. Butler writes to his wife, “I want the people to know that Gov Baker of Iowa armed us with old muskets not worth a cuss & he knew it & then reported us as fully armed to General Curtis, who as soon as he found out the matter, gave us good ones & no thanks to Baker”(Butler papers, 10-28-1862, pg 2). Although this integrated brigade was ill-equipped for victory, they prevailed. Black soldiers fought with a sense of pride for their country, for their freedom and for the dignity of basic liberties that had been denied them for too long.

The American Battlefield Trust, a charitable organization that primarily focuses on the preservation of battlefields from the American Civil War, the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, details events leading up to and resulting from the Battle of Milliken’s Bend. Included is an excerpt from their description of the battle, which works to give setting to Butler’s letters:

In late May, 1863, as his Army of the Tennessee encircled the strategic Mississippi River town of Vicksburg, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant established advanced supply bases on the Yazoo River north of the city to feed his army…At the latter, several newly-recruited black regiments were posted to defend the facilities. Confederates, seeking to disrupt Grant’s supply lines, developed plans to attack the bases on the west side of the river. On June 7, the Texas Division under Maj. Gen. John G. Walker attacked the garrison at Milliken’s Bend…Lieb’s former slaves, with little training, fought valiantly against their attackers…Although a small battle, the result proved that Black Union soldiers would fight hard for their freedom.

In historiography, this battle is often overlooked because of the large presence of Black Union soldiers. However, this battle, fought by Butler and his comrades, proved to be a significant victory for the Union army, revealing the resilient nature of disparately supported Black soldiers. Throughout his letters, Butler delivers detailed play by play of what was happening around him; he was observing and living history, then sharing it with his wife through his letters home. In some instances, he was not able to write back to his wife for weeks in between. The uncertainty of the status of his life and the patience to wait for these letters, brings value to them and their inside knowledge of the battles. As he gets closer to the Battle of Milliken’s Bend, Butler shares specific tasks he and others had to do in order to survive:

Every team from 4 to 6 Infantry riding in the wagon in full shooting and [livery] as a part of the guard for them, which opposite our camp they halted and waited a few moments when some 200 cavalry came thundering down the road and past all the teams till out ahead (they were the rest of the guard) then the command “forward march” came. Whips cracked and all started off on a gallop… They came back the next day with 90 loads of corn, potatoes (sweet) etc. gathered from the Secesh. Such is war. Killing and robbing go hand in hand and can’t be helped.

War can often highlight the corruption within governments and military officials. Butler creates a space to reflect on humanity’s values through his letters to his wife and remember those who cared for him before taking on his military duties. Within one of his letters, he reflects on the times he once enjoyed with his own wife and children:

The Chaplain’s wife was along with a baby. I heard it cry one night after I lay down & up I jumped and got after the baby I tell you it made me think of home & when I left I dreamed of you & our baby what may become of me I can’t say but I’ll keep you & the children stowed away in a snug corner of my heart, till I wake (if I do) in the unknown hereafter.

In this intimate moment, Butler gives us a full view of the isolation from and nostalgia for his family that occurs within the military and during war. In a later letter to his daughter and wife, Butler expresses deep emotions that often contradict the killing and robbing mentality needed for survival during war. Instead, he shows a more sensitive and intimate side, pleading, “write again Ida, Pa reads your little letters with tears in his Eyes & you know it does me good to cry once in a while.”

Digging into the letters of the Anson Butler papers, one uncovers the world of a soldier who depicts firsthand accounts of the brutality of the Civil War. He retraces the difficult journeys, both mental and physical, that coincide with surviving in a deadly war. Through personal letters we can observe day-to-day life during wartime, reading the thoughts and wishes soldiers felt most critical to impart on loved ones waiting back home. On the other hand, sharing experiences through letters can ease pressure off soldiers, knowing that someone is listening to what you are going through. Having the ability to personally share through letters about one’s experience, whether in war, during a transition into higher education, or after one’s first day on the job, is not only refreshing, heart breaking, and stress relieving, but it allows for in depth and personal conversations between you and the recipient, wherever you are.

Information about Anson Butler and Milliken’s Bend come from these resources:

Overview of Milliken’s Bend on American Battlefield Trust

University of Iowa’s DIY History, Anson R. Butler Letters 1861-1900

Images from Iowa Digital Library