This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the fourth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series has run weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020.

The Martha Ann Furgerson Nash papers are filled with information about her activism as part of the National Council of Catholic Women (NCCW) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), plus insight related to the legacy of Furgerson and her family. Furgerson was born September 26, 1925 in Sedalia, Missouri. She later attended school in Waterloo, Iowa, graduating from East High School in 1943. While earning a BA in history with honors from Talladega College in 1947, Furgerson found love and married Warren Nash. While raising all of their seven children, Nash focused on community engagement, on the local, national, and international level.

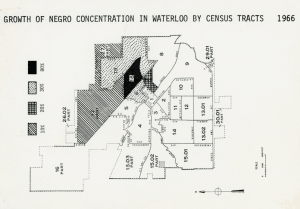

For over a decade, beginning in 1962, Nash served as the director of the Black Hawk County Chapter of the NAACP. Throughout her time with the NAACP, Nash was a part of the Cities Task Force for Community Relations with the League of Iowa Municipalities, which emphasized housing, employment, education, and community relations with law enforcement as pressing issues for Iowa’s Black community. As director of the Black Hawk County Chapter of the NAACP, Nash had the opportunities to display her research and the work of the League of Iowa Municipalities. Within this collection there are a series of six editorials addressing issues of civil rights in metropolitan Black Hawk County on the KWWL television station. KWWL went on air in 1947 as Ralph J. McElroy, founder of KWWL, “realized that Waterloo needed more radio stations.” KWWL-TV aired in November of 1953.

The scripts for the KWWL editorial series, preserved in Martha Nash papers, aired between February 12-17, 1968. They addressed topics such as housing, education, employment and community relations which were areas of concern for the task force that Nash was a part of. After the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, the program returned for a final address and call to action on April 8, 1968.

The first report provided the audience with an overview of recurring issues that the Black community encountered. The second report pressured members of the Waterloo, Cedar Falls and Evansdale communities to lend formal support in dismantling discrimination against non-white people seeking to buy a home or rent, by writing their city council in favor of an open housing ordinance. The third report detailed a “crash, saturation program” on appropriate techniques for police communication with Black residents. Not to be one sided, the report pushed the Black community to invite police officers to as many functions as possible to alleviate tensions between the two groups. The remaining reports encouraged businesses and labor organizations to “adopt resolutions supporting the elimination of racial discrimination in employment” and highlighted the disadvantages of segregation in schools.

These issues raised by the NAACP and the League of Iowa Municipalities are still being fought over today. Nash envisioned, that, as she stated “if our determination lags, if we become petulant, if we delay in facing up to the tough decisions immediately ahead, we will pay a huge price in the future.” While young Black and Brown people across the world continue to be targets of racial injustices, mass incarceration and murder, we all need to act now before it is too late. In the wake of Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination, the final report stated:

“We ask that Americans everywhere dedicate themselves to this proposition and work together toward the fulfillment of the dream of Martin Luther King. If we can’t, the future of this noble experiment in government by the people looks bleak. If we can, America has a chance to really be the land of the free and home of the brave.”

Sentiments such as the one above spoke to the need for societal change. Nash challenged Black people to advocate for themselves, while challenging non-Black community members to join the movement. Martha Nash will forever be an example of an individual who was optimistic for the future.