“Schöner Bruder,” “Ma Chère Petite,” “Sonny Boy,” Honey Child,” these are just a few of the salutations used by Dorothy and Warren “Jack” Wirtz in their letters to each other. Although their greetings may have been somewhat tongue in cheek, Dorothy and Jack’s correspondence reveals a relationship full of common interests, good humor, and affection. What helps make this so immediately apparent is that Wirtz kept her family correspondence separate from the rest. Additionally, she transcribed over 1000 pages of it, ensuring its legibility. In fact, the order of and attention Dorothy paid to her correspondence gives insight into how she prioritized her relationships and organized her life.

When I began to process this collection, I conducted a quick survey of its boxes and determined that Wirtz’s correspondence and diaries comprised over half of it. Normally, processing these portions of collections for use would involve a straightforward, chronological order. But, Wirtz was a little more complicated than that. She kept letters from her parents and her brother separate from her letters from friends and colleagues, and kept correspondence with students in a box on its own. Additionally, she kept postcards from her family distinct from all other correspondence.

Although the original letters remained, Wirtz also transcribed many of them, occasionally editorializing. After Jack’s “Hello. Hawaii?” she explained, “This must have been a greeting heard frequently on radio.” In a 1934 letter she had written to her brother about the notorious bank robber Pretty Boy Floyd, “At last you are in no immediate danger. ‘Pretty

Boy’ Floyd has been killed.” Next to her transcription of that letter she wrote in red pen “Mother worried about him being at large while Jack hitchhiked to various places.”

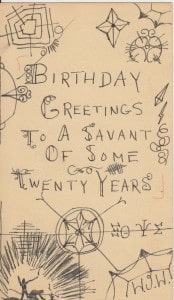

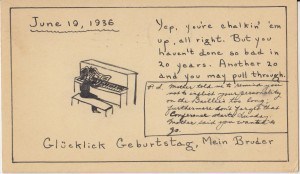

Recognizing Wirtz’s arrangement of her letters as intentional, I chose not reorganize them, but instead followed the archival principle of original order. Except in cases where letters are misfiled, I maintained Wirtz’s order rather than imposing an artificial one. Not only is this simpler for me as a processor, but it gives future researchers the benefit of seeing Wirtz’s correspondence as she did, with the spheres of her life distinct from each other. Dr. Wirtz, professor of French is stern, incisive, and businesslike. But the letters of “Dot” to her family are more playful. It’s a delight to see her brother play right along without interruption. The siblings sprinkled their letters with French and German, closed them with phrases like “all agog” and “d’amour,” and generally infused their prose with a mock formality.

“Would it derange you at all if we drop in on Sunday?” Dorothy asked her brother one September while he was living in Grinnell.

“Derange me?” he responded the next day, “Why I should say not. I’ll be tickled to have you come.”

Born one year apart, the siblings were as close in age as they were in everything else. Both pursued higher education, wrote poetry, spoke multiple languages, and traveled abroad. Dorothy outlived her brother by over 40 years. But you can conjure up parts of their relationship by traversing their correspondence, just as Dorothy might have each time she sat down to transcribe one of their letters.