This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the ninth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020.

In honor of Latinx Heritage Month (September 15 – October 15), this post draws attention to an individual and family history that sheds light on the intersection of Black and Latinx experience and activism in Iowa.

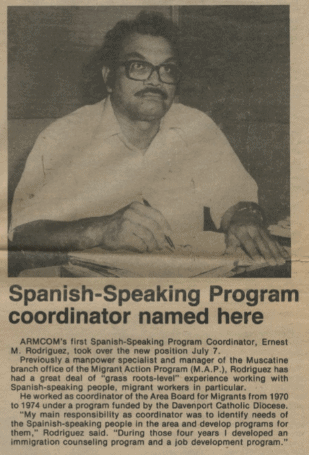

In recognition of his lifelong activism for the causes of labor, education, and civil and human rights, Ernest Rodriguez was inducted into the second Iowa Latino Hall of Fame in 2018. Beginning in the 1950s, Rodriguez helped to organize the Davenport council of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). In the 1960s and 70s, he served on the Davenport Human Relations Commission, served as director of the Area Board for Migrants, and as coordinator of the Spanish Speaking Peoples Commission. As a union organizer and advocate for workers’ rights, he co-chaired the Quad City Grape Boycott Committee to support the nationwide boycott of California table grapes led by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. Although Rodriguez identifies strongly with his Chicano heritage, his own experience growing up in an interracial family undoubtedly informs his broader commitment to fighting against the racism, discrimination, and inequality shared by Latinos, African Americans, and other minorities in Iowa and the U.S.

The Ernest Rodriguez papers are part of a rich set of collections in the Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA) that include letters, speeches, diaries, photographs, and over eighty oral histories documenting the experience of Latina women and their families and communities in Iowa. A large selection of that material is available in the Iowa Digital Library. These collections also inform the IWA website, Migration is Beautiful, a digital humanities project that “highlights the journeys Latinas and Latinos made to Iowa and situates the contributions of Latino communities within a broader understanding of Iowa’s history of migration and civil rights.” IWA also holds the papers of Ernest Rodriguez’s older sister, Estefania Joyce Rodriguez, who was also a member of the Davenport LULAC council and a great chronicler of her family’s history through the preservation of photographs.

Ernest Rodriguez was born in 1928 in the predominately Mexican settlement known as “Holy City” in Bettendorf, Iowa. His father, Norberto Rodriguez, was raised on a small ranch in the State of Jalisco, Mexico; his mother, Muggie Belva Adams Rodriguez, was an African American woman born in Balls Play, Alabama. Both migrated north and, eventually, to Iowa in pursuit of new opportunities in the 1910s. Following the death of her first husband, Muggie Adams ran a boardinghouse in the predominately African American town of Buxton, Iowa, catering primarily to “miners and Mexican laborers who worked as section hands on the railroad.” It was there that she met Norberto Rodriguez, who she married in 1920. The couple and their growing family settled in Bettendorf, Iowa in 1923.

Ernest Rodriguez was part of an extended interracial family that included his mother and father, eight siblings, relatives in Mexico, and the families of his maternal aunt and uncle, Monroe Milton Adams, Jr. and Adaline Adams (known as “Aunt Tiny”). Rodriguez described his mother as being “of a very light complexion with mixed African American, White, and Native American Indian bloods.” Growing up in Iowa, Rodriguez recalled the way his mother’s cooking blended all of these cultures. She made Mexican rice and fideo, cornbread and cobblers, chitterlings, posole, and “fried Indian bread.” This she fed to her family, as well as to the needy men and women that came their way during the Great Depression. Both Ernest and Estefania Rodriguez recalled their mother’s generosity and the fact that “She never looked down on anybody.” Witnessing her struggles with poverty and racism, they both saw her as a model of independence, determination, and perseverance.

The Holy City barrio where Ernest Rodriguez was born was a working-class, mostly Mexican community which offered sparse accommodations to workers in the Bettendorf Company’s foundries. Although most of Holy City’s residents were Mexican immigrants by the 1920s, a few Greeks and African Americans also lived there. Latinos and African Americans shared many experiences in Iowa, including racial stereotyping; limited employment opportunities that often relegated men to the most dangerous, low-paying work and women to domestic service; housing discrimination; and segregation in churches, movie theaters, barbershops, and schools. When the Rodriguez family moved to Davenport, Iowa in the late 1930s, they immediately faced a petition campaign organized by white residents who wanted to drive them out of the neighborhood. Rodriguez recalled,

I remember that it was then I began to really know what prejudice and discrimination meant, because I felt it all around me. The kids in the neighborhood were all white and when they got mad at you, they [hurled racial insults]. As I grew older I found out that there were certain places you couldn’t get a job because of employment discrimination. Certain taverns and restaurants you avoided for the same reason. You were more likely to be stopped for questioning by the police. It seemed that a disproportionate number of minorities were arrested and convicted for crimes than whites. This is true today.

Although much of Ernest Rodriguez’s activism has focused on issues that impact Chicano communities in particular, he has also operated from an understanding of the shared oppression faced by all minorities living under systemic racism. Rodriguez was a Chairman and leading member of the Minority Coalition, which he described as “a banding together of organizations such as NAACP and LULAC whose aims are to work for the betterment of the black and Chicano (Mexican-American) Communities.” He challenged the racism and classism that undergirded the education system, not only for ESL students, but for all “Children of minority groups [who] are victims of discriminatory middle-class thinking.” As a leader in LULAC Council 10, he nurtured a strong relationship with Davenport’s League for Social Justice and the Catholic Interracial Council as they worked to combat racism and demand equal access to housing and employment. And as a member of the Davenport Human Relations Commission he worked to address “race discrimination in housing, employment, and education” and developed a police-community relations program meant to challenge the racist treatment of Chicano and African American citizens by police in the Quad Cities. Rodriguez was also an early feminist, noting in a 1970s radio broadcast that Chicano women, like African American women, faced “the double discrimination of race and gender.”

Even after he retired from his position as Equal Employment Manager at the Rock Island Arsenal in the 1990s, Ernest Rodriguez remained active in the Davenport LULAC council and regularly wrote opinion pieces published in local newspapers about racial justice. He stands as an example of the power of community activism and the impact of local leaders who relentlessly work to promote social justice at the local, state, and national level. Ernest Rodriguez’s life and activism also illuminate the longstanding presence and contributions of Latinos and African Americans to the Hawkeye state, as well as our long history of racism.

Latinx history is Iowa history.

Black history is Iowa history.

The ongoing fight for racial justice is Iowa history.

References:

Omar Valerio-Jimenez, “Racializing Mexican Immigrants in Iowa’s Early Mexican Communities,” Annals of Iowa, vol. 75, no. 1 (Winter 2016): 1-46.

Janet Weaver, “From Barrio to ¡Boicoteo!: The Emergence of Mexican American Activism in Davenport, 1917-1970,” Annals of Iowa, vol. 68, no. 3 (Summer 2009): 215-254.

Iowa Women’s Archives, Migration is Beautiful, http://migration.lib.uiowa.edu/, October 14, 2020.