The University of Iowa Libraries Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio (DSPS) has launched a unique digital resource for educators, students, and community members. Health Story Hub is an open access website that offers a searchable database of stories about health, illness, and healing for teachers to use in classrooms, community groups and clinics. Kristine Muñoz,Continue reading “UI Libraries Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio launches Health Story Hub, NEH-awarded digital project collaboration”

Tag Archives: digital humanities

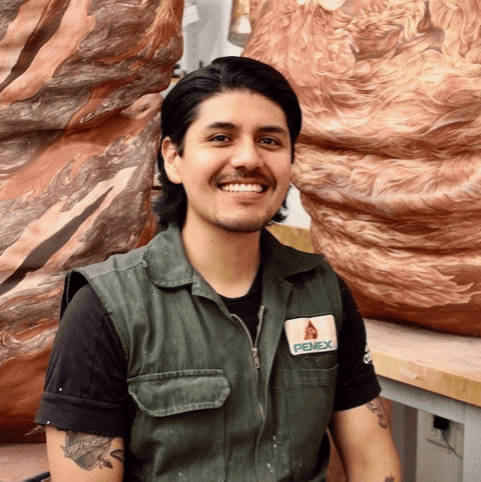

Javier Espinosa Momox’s summer fellowship blog

I have been working on my digital archive, you can view it here. HERENCIA MEANS HERITAGE HERENCIA MEANS HERITAGE IS A DIGITAL ARCHIVE THAT SEEKS TO HELP GIVE REPRESENTATION TO MARGINALIZED AND INVISIVILIZED ARTISAN COMMUNITIES AS WELL AS INCIPIENT CRAFT PROPOSALS.MISSIONHERENCIA MEANS HERITAGE AIMS TO CELEBRATE AND PRESERVE THE RICH TRADITION OF TRADITIONAL HANDCRAFTED POTTERY THROUGH COMMUNITY-BASEDContinue reading “Javier Espinosa Momox’s summer fellowship blog”

Introducing the Studio’s 2024 Summer Fellows

The University of Iowa Graduate College and the UI Libraries Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio are excited to announce that 10 graduate students have been selected for the 2024 Studio Summer Fellowship program. These individuals will soon take part in an eight week course that provides mentored digital scholarship experience, as well as trainingContinue reading “Introducing the Studio’s 2024 Summer Fellows”

The Literary Heritage of Cornell College: Creating Digital Resources to Support Our Community

By Miranda Donnellan Archives are not infallible. As a librarian, this is a fact of life. But as a digital humanist, I am empowered to solve this problem. For my Public Digital Humanities Certificate capstone, under the guidance of Cornell College’s Professor Kirilka Stavreva, I created a digital archive highlighting the works of Jewel BothwellContinue reading “The Literary Heritage of Cornell College: Creating Digital Resources to Support Our Community”

“Scholarship is Scholarship”: Identity Crisis in the Digital Humanities

When I meet someone, our introduction typically goes something like this: What do you do? I teach college literature and I’m a graduate student. Oh, what do you study? Victorian Literature Oh, like Jane Austen, and stuff? …sure. There is always more we can say about ourselves, our interests, and our work. If I decideContinue reading ““Scholarship is Scholarship”: Identity Crisis in the Digital Humanities”

Mediocritas in the Digital Humanities (and in My Life)

…evelli penitus dicant nec posse nec opus esse et in omnibus fere rebus mediocritatem esse optimam existiment. “They say that complete eradication is neither possible nor necessary, and they consider that in nearly all situations that the ‘moderation’ is best” (Cicero, Tusc. 4.46). In my last few weeks here at the Digital Scholarship & PublishingContinue reading “Mediocritas in the Digital Humanities (and in My Life)”

When to Work Alone, and When to Ask for Help

I’m not a “tech” person. Naturally, computers (amongst other software and gadgets) make up a normal part of my day-to-day routines, and while I feel perfectly comfortable “tinkering” around with new gadgets and programs, the language of code and other seemingly mysterious components of the “digital” in academia elude me. No, I study stories; IContinue reading “When to Work Alone, and When to Ask for Help”

The Journey through the Realm of Process

“Process is the new god…Digital Humanities mean iterative scholarship…It honors the quality of results; but it also honors the steps by mean of which results are obtained as a form of publication of comparable value. Untapped gold mines of knowledge are to be found in the realm of process” (The Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0, 5).Continue reading “The Journey through the Realm of Process”

DH Salon Recap: “Whitman’s Letters—The Collaboration of the Walt Whitman Archive Correspondence team”

On February 12, 2016, the Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio hosted the second DH Salon event of the semester—a collaborative presentation highlighting the Walt Whitman Archive’s Correspondence project. Presenters included Ed Folsom (Roy J. Carver Professor of English and Co-Director, Walt Whitman Archive), Stephanie Blalock (Digital Humanities Librarian & Associate Editor, Walt Whitman Archive), StefanContinue reading “DH Salon Recap: “Whitman’s Letters—The Collaboration of the Walt Whitman Archive Correspondence team””