When I meet someone, our introduction typically goes something like this:

What do you do?

I teach college literature and I’m a graduate student.

Oh, what do you study?

Victorian Literature

Oh, like Jane Austen, and stuff?

…sure.

There is always more we can say about ourselves, our interests, and our work. If I decide that I want to go into greater depth, I might specify to this person that—while I love Austen’s novels—the literature I study typically comes later in the century than Austen’s. In fact, I am currently writing a dissertation that examines late-nineteenth century British literature that deal with issues of social reform and resistance. And if I’m feeling really chatty, I might add that my dissertation uses literary cartography and geocriticism to look at places where particular communities lived, where they were forced to move, and how literary accounts correspond with these maps.

… but I digress.

The point is, in many circles of academia, we’re asked to clearly define our disciplines or areas of expertise: late-nineteenth-century British literature, twentieth-century American history of baseball, biochemical engineering, etc. We often have titles, categories, or topics that delineate our “areas” into nice and neat sound bites. I’ve quickly found that is less true of our work in the digital humanities (DH). What are the digital humanities? Or, better yet, how am I defining DH? When Clifford A. Lynch, Executive Director of the Coalition for Networked Information (CNI), was asked how he would define “digital scholarship?” his response was seemingly evasive, but honest:

“Digital scholarship is an incredibly awkward term that people have come up with to describe a complex group of developments. The phrase is really, at some basic level, nonsensical. After all, scholarship is scholarship” (10).

Even though I know this—that scholarship is scholarship—I’ve still struggled with my relationship with the digital humanities as I work within “the field,” but still feel outside of it. I turn back to the continuous question that many before me have posed: What does it mean to work in the digital humanities?¹

As I look around this morning, sitting at one computer of many in the Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio (DSPS), I assume that behind many of the screens my summer fellowship colleagues are busy coding or revising code that they’ve been working on this summer. This seems like the obvious addition to make something digital… get to coding. (Keep in mind I say this with about the same amount of “coding knowledge” as my pet terrier.) I’ve sat in on conversations about “coding concerns,” like: when to write new code, and when to use what’s available; when to take a coding break and focus on thematic and theoretical concerns; and which types of coding are sustainable and transferable across platforms. And yet, the truth is, I don’t code! Sure, I was exhilarated when I figured out how to create a hanging indent in html (as demonstrated in my earlier post); I wanted my bibliographic entries appear in correct MLA format in Omeka.² However, I don’t code and I don’t program; I read, I research, and I analyze.

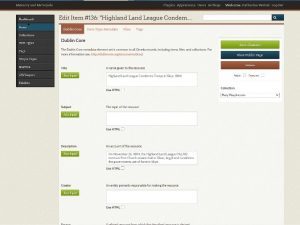

Fig. 1, Screen shot of record entry in Omeka

My work became “digital” when I applied for assistance to create a map of where characters lived and traveled in William Morris’s utopian romance, News from Nowhere. Then when several of my colleagues assisted with this endeavor,³ my project expanded to analyze the literary cartography and geography of several authors and their work in my dissertation. Most of my time on the “digital” side of things has been simple data entry. I’m working with Neatline (as a plug-in for Omeka), and after I finished importing my first batch of records from an excel spreadsheet (in csv format), I’ve simply been revising records in Omeka and adding new ones (fig. 1).

For a while, I felt self-conscious about this perceived gap between my assumptions about DH and my own skills and my project. I wondered if my records and maps would reveal anything useful and hoped that this wasn’t all a waste of time. I shared my concerns with White, my point person in DSPS, embarrassed to admit my uncertainty and expose my potential for failure. However, she reassured me that almost everyone feels this way at some point, regardless of their expertise: “Working in the digital humanities is about figuring out how to ask the right questions and who to ask.” Basically, it means asking questions all the time to everyone who will listen and being ready to learn.

How is this different from “non-digital” scholarship? It isn’t, really. As a DH project, my work this summer has demanded my attention to process (how and why I enter certain records) and my desperate reliance on others.4 Now these demands have been digital-specific—in that I am working with online platforms and plug-ins, and working with a digital librarian (shout out, Nikki!)—but they are not specific to digital work generally. All scholarship requires diligent consideration of process and—although many of us in the humanities try to deny it—scholarship is a collaborative endeavor. As Lynch says, “scholarship is scholarship,” and the tools we use don’t change that. To say that I work in the digital humanities, doesn’t mean that I am a computer guru or can code with the best of ‘em. All it means (for me), is that I have found useful digital tools (created by someone else and used by many others) to address a research question.

As I study the work of Mathilde Blind and Mary Macpherson, I am thrilled to see that my data reveals a distinction in the Neatline map between the places these authors lived (London and Glasgow) and the northern Highlands they portrayed in their poetry and political discourse (see figures 2 & 3). I am continuing my research in additional Neatline exhibits to address similar discrepancies between how a place is portrayed and how it is experienced. Neatline allows me to demonstrate these points of interest, but it is only one part of my scholarship puzzle. Similarly, the digital humanities can be useful and impactful, but—as I have found—DH is not a helpful or neat category to describe scholarship; it’s messy and ambiguous. Instead, I adopt Lynch’s statement as an adage for our generation of scholars, remembering that while digital tools and techniques can help us answer our questions: “scholarship is scholarship.”

Notes

¹ For additional discourse on what it means to work in the digital humanities see: Edward Ayers, “Does Digital Scholarship Have a Future?” Educause Review, July/August 2013, pp. 24-34.

² K.E. Wetzel, “When to Work Alone, and When to Ask for Help.” University of Iowa Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio Blog, 13 July 2017.

³ Laura Hayes and Caitlin Simmons are currently working on a larger and more in-depth mapping project on William Morris’s News from Nowhere, for the William Morris Archive (WMA). They are working with Professor Florence Boos, the general editor for WMA; Robert Shepard, GIS specialist with the Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio; and additional graduate students at the University of Iowa, including Kyle Barton.

4 I am gratefully reliant on my project “point-person,” Nikki White, Digital Humanities Research & Instruction Librarian at the University of Iowa DSPS. She assists with the coding and programing side of things, but more importantly she has been a mentor through the “how and why?” issues of my project (e.g. which platform to use, how to structure my archive, the limitations of any given visualization, etc.), so that I can be intentional with how I enter and store my data—and how I use it in my writing and teaching.

Works Cited

Lynch, Clifford A. “The ‘Digital’ Scholarship Disconnect.” Educause Review, May/June 2014, pp. 10-15.

Boos, Florence, editor. The William Morris Archive, url: morrisedition.lib.uiowa.edu/.