DIY History began as an online experiment in Spring 2011 with the Civil War Diaries and Letters Transcription Project, and quickly became a trove of local, national, and international artifacts made available and searchable online. As we celebrate 100,000 pages transcribed, let’s look back on some of DIY History’s history! After its initial success andContinue reading “DIY History Reaches 100K Pages Transcribed!”

Category Archives: DIY History

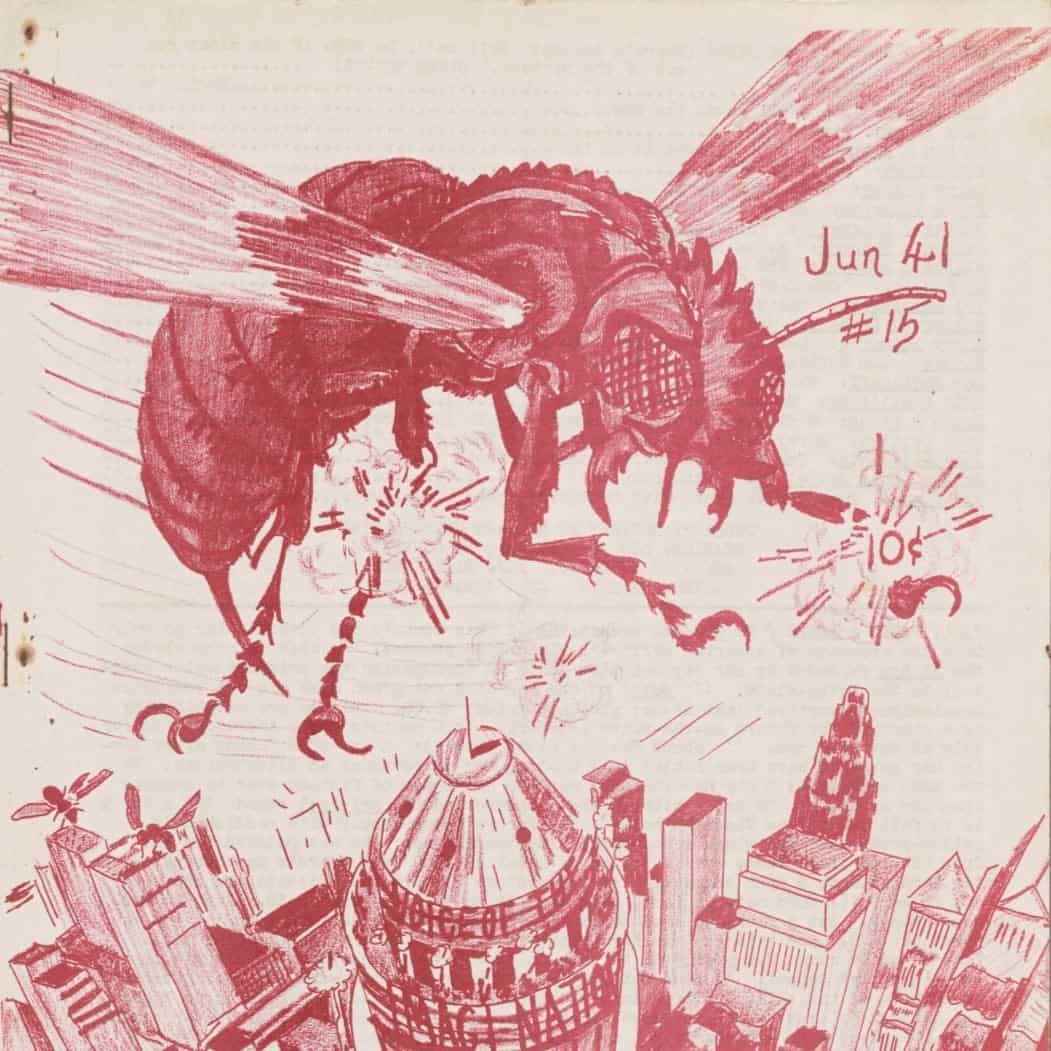

Fanzines, the Roots of SF, and the Dual Enrollment Classroom

The Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio proudly shares this guest blog post from Russell Aaronson of Coral Springs High School, Coral Springs, Florida, detailing his and his students use of the Hevelin Fanzine Collection in DIY History. * * * Clicking through The University of Iowa’s DIY History Hevelin Fanzines archive sent me back toContinue reading “Fanzines, the Roots of SF, and the Dual Enrollment Classroom”

Celebrating Women in Iowa’s Past

Today, in celebration of International Women’s Day, we reflect on the progress and many achievements that women, past and present, have made around the world. The origins of this day can be traced back to the early 1900s, marked by a strike for better working conditions for women in the garment industry. While the strike didn’t takeContinue reading “Celebrating Women in Iowa’s Past”

Another Milestone for DIY History!

It was just over two years ago that DIY History reached its amazing 50,000-page transcription benchmark! This past week we achieved 75,000, and we’d like to take the opportunity to talk a little bit about the elements that have led to this amazing growth. Available Collections Since reaching 50,000 pages, six new collections have been added including ScholarshipContinue reading “Another Milestone for DIY History!”

Women, Scholarship, & DIY History

Earlier this week, the Studio launched Scholarship@Iowa, a curated set of pages promoting scholarly archives related to historically underrepresented groups. To introduce that initiative I wrote a blog post touting the merits of these archives and their ability to help us see ourselves as a part of longstanding tradition of excellence and discovery at theContinue reading “Women, Scholarship, & DIY History”

Scholarship@Iowa: celebrating diversity in the archives

We in the Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio are reminded – daily – of the incredible digitized material held in our archives. Letters, dissertations, scrapbooks, newspapers, photographs spanning hundreds of years can be found in places like the Iowa Digital Library and Iowa Research Online. These collections and this scholarship remind us of who has passed throughContinue reading “Scholarship@Iowa: celebrating diversity in the archives”

The DIY History transcription API

Since the launch of the Civil War Diaries & Transcription Project, the goal of DIY History has been to promote the University of Iowa Libraries digital collections. Part of this mission includes making the trove of transcriptions from handwritten diaries, manuscripts, and letters widely available to researchers for use in their work. At the timeContinue reading “The DIY History transcription API”

DIY Natural History

Together with the University of Iowa Museum of Natural History, the UI Libraries launched a new DIY History collection, the Egg Cards, a little over a month ago. These field note cards were collected by amateur ornithologists during the late 1800s/early 1900s in Iowa and elsewhere, for the purposes of identifying egg specimens in nests. Continue reading “DIY Natural History”

Contributing in code

For librarians, particularly those in academic settings, an important part of the job is contributing to the development of the profession; traditionally, this has included tasks such as giving presentations at conferences and publishing articles in scholarly journals. But thanks to the evolving nature of our work and to innovations on the part of our developers, the University of IowaContinue reading “Contributing in code”

DIY History celebrates 50,000th transcription!

As DIY History, the University of Iowa’s transcription crowdsourcing site, has inched toward its 50,000th submission, we’ve been looking forward to reaching such an amazing milestonetemp — hence the queued-up cake gif. But as it turned out, we weren’t quite prepared for how it went down today. On the heels of some high-profile attention from BuzzFeedContinue reading “DIY History celebrates 50,000th transcription!”