Zachary Turpin, a PhD candidate in English at the University of Houston (who made international headlines in April 2016 with his discovery of a previously unknown journalistic series by the poet Walt Whitman entitled “Manly Health and Training”) has made another major find: a long-lost, secret novella, also authored by Whitman, entitled Life and AdventuresContinue reading “Announcing “A Rich Revelation”: Zachary Turpin Discovers Lost Novella by Walt Whitman”

Author Archives: sblalock

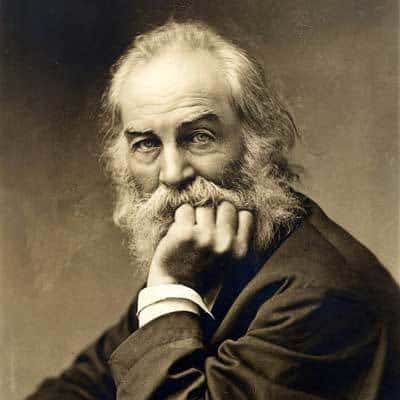

The Discovery of “Manly Health and Training”: Walt Whitman’s Long-Lost Guide to Getting the Body You’ve Always Wanted

In the third open-access issue of the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review (WWQR) Editor Ed Folsom and Managing Editor Stefan Schöberlein publish in full a newly discovered book-length work by the poet Walt Whitman entitled “Manly Health and Training.” Zachary Turpin, a PhD candidate in English at the University of Houston, recently discovered “Manly Health and Training,”Continue reading “The Discovery of “Manly Health and Training”: Walt Whitman’s Long-Lost Guide to Getting the Body You’ve Always Wanted”

DH Salon Recap: “Whitman’s Letters—The Collaboration of the Walt Whitman Archive Correspondence team”

On February 12, 2016, the Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio hosted the second DH Salon event of the semester—a collaborative presentation highlighting the Walt Whitman Archive’s Correspondence project. Presenters included Ed Folsom (Roy J. Carver Professor of English and Co-Director, Walt Whitman Archive), Stephanie Blalock (Digital Humanities Librarian & Associate Editor, Walt Whitman Archive), StefanContinue reading “DH Salon Recap: “Whitman’s Letters—The Collaboration of the Walt Whitman Archive Correspondence team””

Workshop Wrap-Up: An Introduction to TEI/XML

On Saturday, November 7, 2015, I taught an introductory TEI/XML workshop for fourteen attendees, including graduate students from several disciplines and staff members at the University of Iowa Libraries. The workshop was primarily dedicated to providing an overview of text encoding or adding code to a text in order to create a machine-readable version. TextContinue reading “Workshop Wrap-Up: An Introduction to TEI/XML”

DH Salon Recap: The Walt Whitman Archive’s pre-Leaves of Grass Fiction Project

On Friday, Oct. 23rd, the Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio hosted the fourth DH Salon of the semester. I was very glad to welcome an enthusiastic group of faculty, staff, and graduate students to the Studio for my presentation, “From Periodical Page to Digital Edition: The Walt Whitman Archive’s pre-Leaves of Grass Fiction Project.” The goal ofContinue reading “DH Salon Recap: The Walt Whitman Archive’s pre-Leaves of Grass Fiction Project”