On February 12, 2016, the Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio hosted the second DH Salon event of the semester—a collaborative presentation highlighting the Walt Whitman Archive’s Correspondence project. Presenters included Ed Folsom (Roy J. Carver Professor of English and Co-Director, Walt Whitman Archive), Stephanie Blalock (Digital Humanities Librarian & Associate Editor, Walt Whitman Archive), Stefan Schoeberlein (Managing Editor, Walt Whitman Quarterly Review & Graduate Research Assistant, Walt Whitman Archive), Alex Ashland (Graduate Research Assistant, Walt Whitman Archive), and Ryan Furlong (Graduate Research Assistant, Walt Whitman Archive).

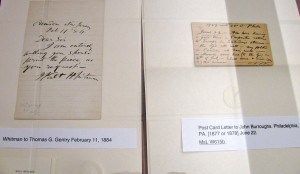

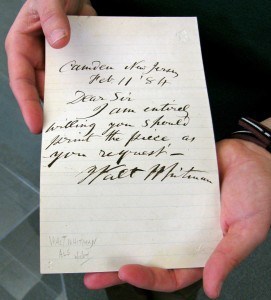

The presentation was accompanied by an exhibit featuring three letters written by Walt Whitman in the 1870s and 1880s. These letters are among the many books and Whitman-related items that are held by Special Collections at the University of Iowa Libraries.

During their presentation, the Whitman Archive Correspondence team shared the digital edition of Whitman’s incoming and outgoing correspondence that they are currently building and gave the audience a behind-the-scenes look at the faculty, staff and student collaborations that make this digital project possible. All of the Correspondence team members at Iowa had the opportunity to share their work and research with the audience. In keeping with the collaborative spirit of the DH Salon, this post, like the presentation itself, reveals the roles of each member of the Whitman Archive Correspondence project team and explains how we make Whitman’s letters available to Archive users.

Stephanie Blalock

During our talk, I discussed my role as the current project manager for the Correspondence project and my efforts to write our grant proposals, design our workflows, and train our staff, including three graduate assistants here at the University of Iowa and an additional graduate research assistant at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. I outlined the need for a digital edition of Whitman’s correspondence and the advantages our editions offers over earlier printed collections. I pointed out that our digital edition not only includes the outgoing and the incoming correspondence, but it is also integrated into the overall search functionality of the Whitman Archive. I also emphasized that our digital edition can easily accommodate newly discovered letters and that it is correctable; as a result, our users often become our collaborators by helping us to catch stray errors in transcription or by providing additional information on Whitman’s correspondents.

Stefan Schoeberlein

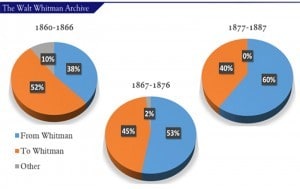

For my part of the presentation, I gave a numerical overview of Whitman’s two-way correspondence and gave some examples of how the Correspondence team is beginning to explore the letters through data visualization and topic modeling. With over 3,775 letters encoded (and most of them already published on our website), we can see some interesting trends emerge from this body of text(s) when we analyze them.

Besides noting an increase of extant Whitman-letters from the 1860s to the 1880s, we also find the ratio of surviving letters to and from Whitman shift (from the former to the latter), allowing us to trace the poet’s rise to celebrity and, hence, the collectability of his letters. I also presented some numerical visualizations of the correspondence and showed that Whitman’s letters address topics ranging from the publication of his various editions of Leaves of Grass to his declining health in his final years. I emphasized that the vast amount of information now available to us and our users makes it clear to us that we–the Walt Whitman Archive and the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review–want to engage (and encourage others to engage) with the two-way correspondence not just as individual texts and exchanges but as data.

Alex Ashland

I outlined some of the major challenges of the Correspondence project that I have encountered during the two years I have spent working with the letters. One of the most challenging aspects of creating a digital edition of the two-way correspondence is that the Archive staff must edit letters by a variety of authors writing from a variety of backgrounds, all with differing degrees of competency and literacy. Whitman received letters from doctors, university professors, book editors and publishers, but also from insane asylum patients, wounded soldiers, and the occasional obsessed fans. As a result, things like author style, syntax, and overall legibility vary drastically from one writer to the next, and the team has to work together to ensure that in the process of editing, things like words, punctuation, and paragraph divisions, remain consistent with the written letter.

I also pointed out that despite these challenges the Whitman Archive thrives precisely because of the unique opportunities it affords archivists and users alike. Because the digital platform and the infrastructure around which it is built is so adaptive and open to immediate revisions, users are always encouraged to contact and interact with members of the Correspondence Project team. And while the various personnel at Iowa have developed a rigorous process of transcribing, encoding, and checking letters, the archive allows for a level of user interactivity that is rarely seen in other digital archives.

Ryan Furlong

For my part of the presentation, I discussed the work I have done as a first-year graduate research assistant for the Walt Whitman Archive. My primary responsibilities have included transcribing, encoding, and verifying Walt Whitman’s incoming and outgoing correspondences for 1887 and 1888. I demonstrated how this three-step process ensures precise and legible transcriptions of manuscript images are displayed for Whitman Archive readers in a user-friendly format and how I work to include pertinent biographical information, annotations, references to other correspondences, as well as the actual content of the letter itself. Ultimately, I showed how my position as a transcriber and encoder serves as a critical first step in accurately recording the contents of Whitman’s (and others’) correspondences before other members of the Archive team process and review them for publication.

Ed Folsom

I reviewed the overall workflow for letters, starting with transcriptions and encoding and extending through first and second checks before coming to me for a final “blessing,” which often involves adding further annotations, clarifying information about correspondents, and correcting transcription errors and typos that have made it through the first checks. I emphasized how the “blessing” by one of the directors serves as the final confirmation of scholarly and editorial accuracy that we can stand behind and stake our reputations as Whitman scholars on. I commented on how there’s a long “workflow” that occurs before we begin the first transcribing work, and that’s the brainstorming at our annual Whitman Archive full staff meeting in Lincoln each summer, where we decide on which projects we want to focus on, strategize about grant applications, decide whether Iowa or UNL (or somewhere else) will take the lead, then work on a grant proposal, the preparation for which often involves the first real steps in the project (generating a list of letters, deciding how many we can promise to the granting agency, and so on).

What our presentation revealed, and what I would like to emphasize here is that the Whitman Archive correspondence project is growing in exciting new ways. We are expanding our research to include topic modeling and data visualization, and an undergraduate intern has recently joined our team. The Correspondence team would also like to become a site where graduate students enrolled in the Public Digital Humanities certificate can complete their Capstone experiences.

Finally, the Walt Whitman Archive, which turns twenty-one this year, is one of the oldest and most comprehensive digital projects in existence, and collaboration between faculty, staff, and students has been one of the keys to its success. As digital humanists often claim, the digital humanities is collaborative in theory and in practice. The Whitman Archive Correspondence project team is one of many living embodiments of that statement on our campus, as the creation of a digital edition of Whitman’s letters depends on the combined efforts of the faculty, staff, and students that were a part of the DH Salon presentation. The Correspondence team believes that when we do not collaborate and communicate with each other, the library, our institutional partners, and even our users, then the people that suffer most as a result of those actions are those who depend on our site for their research, teaching, and pleasure reading, as well as the graduate and undergraduate students we are supposed to be mentoring toward various career options. For us, these are the people that least deserve to bear those consequences. At the end of the day, the Correspondence team firmly believes that one of our greatest strengths is that we are a faculty, staff, and student collaboration.