…evelli penitus dicant nec posse nec opus esse et in omnibus fere rebus mediocritatem esse optimam existiment.

“They say that complete eradication is neither possible nor necessary, and they consider that in nearly all situations that the ‘moderation’ is best” (Cicero, Tusc. 4.46).

In my last few weeks here at the Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio, this thought kept racing back into my mind: mediocritas. My translation for it, “moderation,” is quite poor. In this context, it refers back to the Peripatetic (and generally Greek) concept of the middle state, the mean between two extremes, or the right amount or degree of anything. Today, we know this concept as the “The Golden Mean,” the balance between an extreme of excess and another of deficiency, especially when it comes to virtues and emotions. A soldier must be moderately angry when he runs towards the battlefield. An orator can only effectively argue for his client in court if he’s impassioned by genuine (and moderate) anger and not feigning it.

At this point, I feel obligated to point out that the speaker in Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations was a Stoic and therefore believed that the complete eradication of emotions was possible. He was arguing against The Golden Mean. Unlike the Peripatetic soldier and orator, the Stoic sage chooses not to feel anger at all. He chooses to feel very little.

I am not a Stoic sage. I am far from it. Within these past few weeks, I’ve felt (probably too much) anger and frustration as well as elation and tranquility. Even though I have been rather emotionally immoderate this past summer, I keep thinking over and over again about The Golden Mean, not in the context of my feelings but of my errors.

“They say that complete eradication is neither possible nor necessary.” Whether it is truly possible to eradicate all emotions, it is truly impossible to get rid of error entirely in my project. But is it necessary to do so? As Humanists, we are already comfortable with disagreement, with having multiple competing theories at once that are all possible. We may side with one theory over another, mix a few together, or not care for them at all. All of this makes finding the “truth” and validating results impossible.

I wasn’t the only one to ask this question. Andrew Piper, in his blog post commenting on the Syuzhet R package debate between Matthew Jockers and Annie Swafford, wrote: “What I’m suggesting is that while validation has a role to play, we need a particularly humanistic form of it… We can’t import the standard model of validation from computer science because we start from the fundamental premise that our objects of study are inherently unstable and dissensual. But we also need some sort of process to arrive at interpretive consensus about the validity of our analysis. We can’t not validate either” (4–5).

There’s still a need for lessening the margin for error as much as possible. There’s still a need to approach the “truth” as closely as we can and to validate results. We need a Golden Mean.

For me, finding this balance was (and currently is) a struggle. I had to especially keep in mind the idea of “finding the right proportion for everything.”

Earlier this year, I encountered this problem for the first time. I was trying to record the lexical richness of Cicero’s speeches over his career. I tried doing this by finding the Mean Word Use and Type-Token Ratio for all of the speeches. However, these methods did not suit my corpus. Cicero’s orations ranges from less than 1,000 words to over 20,000. It’s a very imbalanced corpus, and the results reflected that. The speeches with the most words had a low lexical richness because the longer the speech is, the more Cicero repeats words. That was essentially what the results showed.

In this case, my “Golden Mean” was the Yule’s K function available through the langaugeR package in R. This function tries to account for length when calculating the lexical richness of a work. And in this way, I was able to get more accurate results.

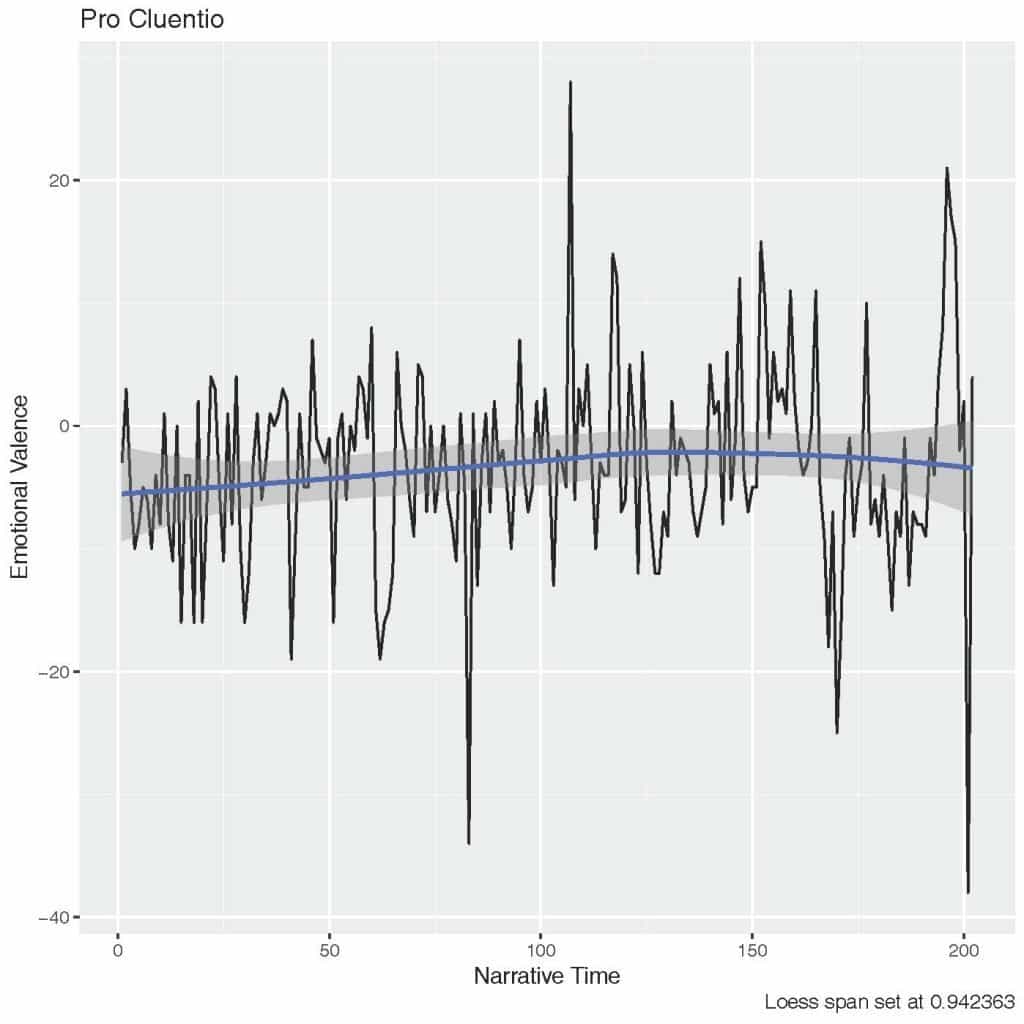

More recently, my struggle had been trying to find the “Golden Mean” for the span of the Loess filter. The same problem came up again: my corpus was imbalanced. This time, it wasn’t only imbalanced in regards to length but in sentiment as well. I’m conducting a sentiment analysis of Cicero’s orations and am trying to find regular patterns in his use of sentiment. So finding the right setting for the filter is crucial. And as you can see from the graph below, changing the span for the filter makes a huge difference:

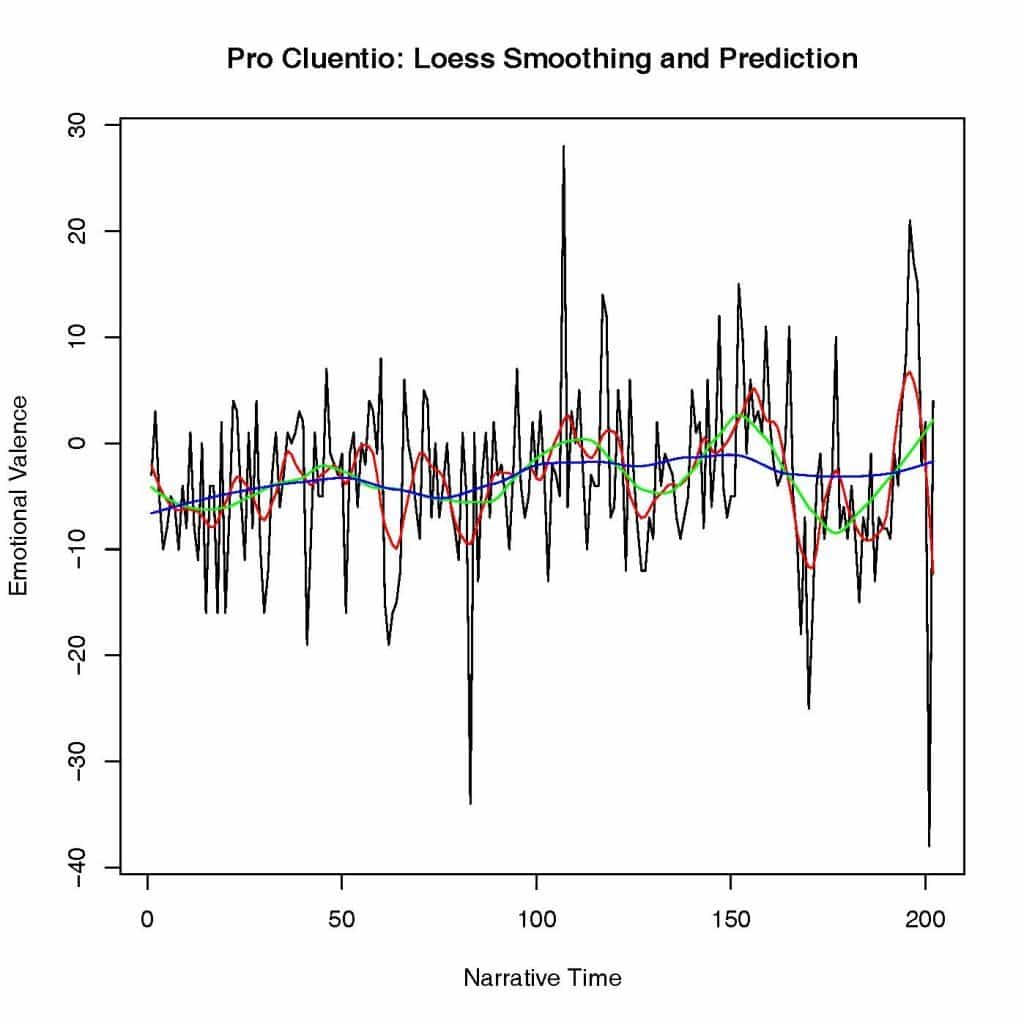

Since all of the speeches vary in length and emotional valence, I was very uncomfortable with the idea of having only one setting for all of them. Luckily, I was able to find a Golden Mean for this too. This time it came in the form of the fanCOVA package for R, which can calculate the optimal span of a vector.

And the following graph is the result of that test:

Hopefully now all of my graphs have the “right proportion.” They might not be wholly accurate, but accurate just enough to stimulate good and productive scholarly work and discussion.

But looking down the line, at the future of my project, I am realizing all of the forms that my Golden Mean can take. I need to find a balance between text mining and traditional scholarship, time spent writing scripts and fiddling with my data sets versus time spent writing my dissertation. I will also need to find a better balance between negotium and otium, work and leisure. And I need to learn to tear myself away from the computer to save my eyes from constantly twitching, which they are doing right now as I’m writing this final blog post.

So while the Stoics may not believe in the Golden Mean, I believe that finding the Golden Mean is critical in my work in the Digital Humanities and life in general. Like Plato once wrote:

…μετριότης γὰρ καὶ συμμετρία κάλλος δήπου καὶ ἀρετὴ πανταχοῦ συμβαίνει γίγνεσθαι.

“For moderation and due proportion are everywhere defined with beauty and virtue” (Plato, Phileb. 64e).

***Finally I would like to extend my gratitude towards everyone at the UIowa Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio for their great help and for being so welcoming. Thank you, Nikki White, for helping me with Gephi and for teaching me about servers. Thank you, Matthew Butler, for aiding me with my R struggles and for introducing me to Python. Thank you, Stephanie Blalock, for being my “point person” and for helping me to stay on task. Thank you, Leah Gehlsen Morlan, for organizing more things for us fellows than I am even aware of. And finally, thank you, Thomas Keegan, for giving all of us this opportunity. I appreciate all of this immensely.

If you are interested in learning more about the debate over the Syuzhet R package, Eileen Clancey has a storified version of it which is available here.

Piper, Andrew (2015, March 25). Validation and Subjective Computing (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site.[Blog Post]. Retrieved from https://txtlab.org/2015/03/validation-and-subjective-computing/ (Links to an external site.)