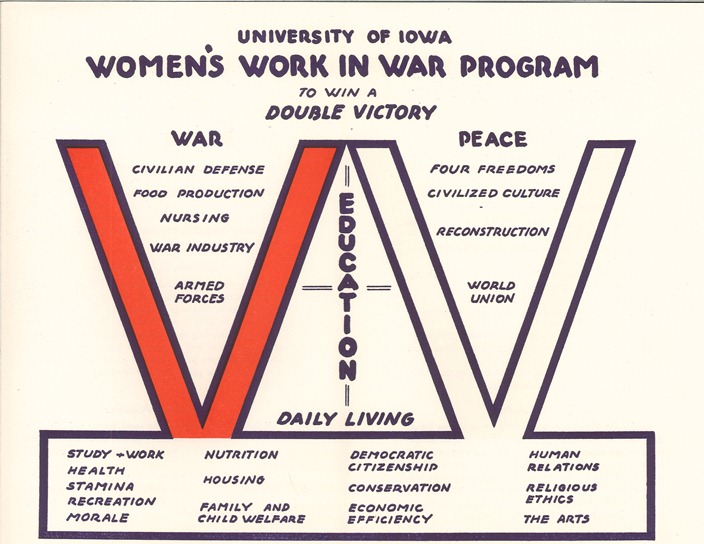

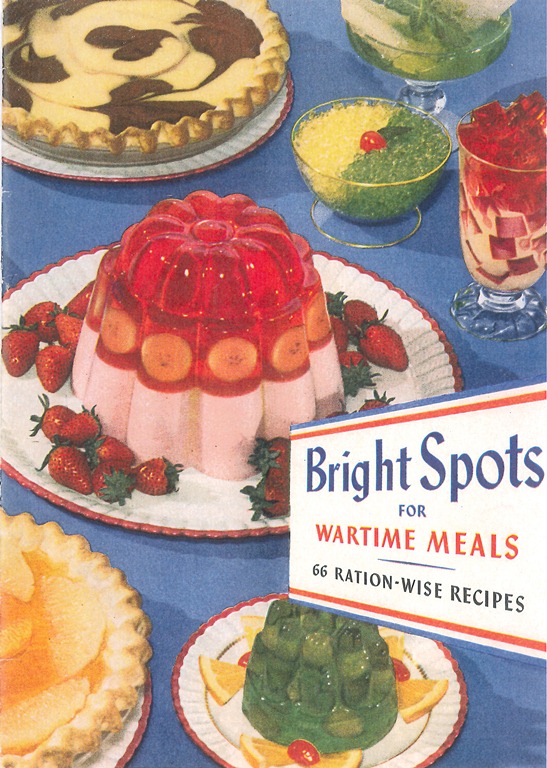

On April 14th Special Collections & University Archives staff visited the International Students’ Cooking Club. György Tóth, a PhD candidate in American Studies and the senior Olson Fellow, prepared some dishes from his native Hungary. Besides the dinner, the evening also featured an introduction to the Chef Louis Szathmáry II Collection of Culinary Arts, with an assortment of pamphlets on hand to browse and a discussion on culture as seen through cooking ephemera led by Outreach and Instruction Librarian Colleen Theisen. Since many of the international students in attendance were from China, the biggest hit of the evening was “The Art and Secrets of Chinese Cooking,” a pamphlet from the Beatrice Foods Company (including the La Choy line of products) from 1949.

Louis Szathmáry was a Hungarian émigré chef, teacher, writer, philanthrophist, an avid book collector, and is considered by many to be the first “celebrity-chef”. The Szathmáry Collection is made up of his extensive collection of books, pamphlets, and manuscripts relating to cooking. You can see digitized versions of many of the pamphlets from the Szathmáry collection here: http://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/szathmary/ and the finding aid to the entire collection is here: http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/spec-coll/MSC/ToMsc550/MsC533/MsC533.htm