Our collections continue to grow through the generosity of our donors, who have made it possible for impressive new resources to become available to our community.

Our collections continue to grow through the generosity of our donors, who have made it possible for impressive new resources to become available to our community.

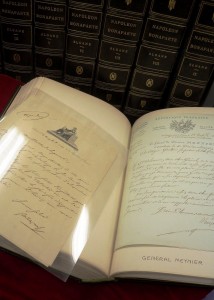

Recently acquired is an extra-illustrated copy of The Life of Napoleon Bonapart by William Sloane, which joins an extra-illustrated set of the same biography that has been part of our collection for over 100 years, and thought to be the only one of its kind. The original set is Monastery Hill bookbinder Ernst Hertzberg’s own extra-illustrated copy of The Life of Napoleon. Hertzberg transformed the set from four to twelve volumes with the addition of portraits, engravings, maps, original letters and more. The set, completed with his own beautiful fine bindings, earned him a gold medal for binding at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. It was purchased by Martha Ranney and donated to the University in 1907. A descendant of the Hertzberg family, Fritz James, CEO of LBS in Des Moines, has now purchased for the UI Libraries another extra-illustrated Life of Napoleon, which was also bound by Monastery Hill. This copy, from Michigan supreme court judge and Napoleon scholar Thomas Weadlock, is bound in 10 volumes and with its numerous illustrations are not only more than a dozen letters from generals and historic figures but also three handwritten and signed letters from Napoleon himself. The two copies together open up countless avenues for scholarship and admiration through their beauty and historic context, through the documents and artifacts bound inside, but also through the study of the collectors and binders responsible for such unique pieces of art and history.

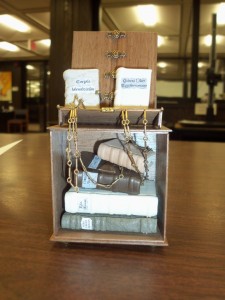

A generous donation from the Angora Ridge Foundation has made it possible for us to complete our collection of works from Vincent Fizgerald & Co., a New York based publisher founded in 1980 that produces limited edition artist’s books. Most of the works from this publisher are hand-printed with handset type, using handmade paper and images created through linocut, itaglio, lithography, silkscreen and photogravure. Several of the new aquisitions are available on our browseable new aquisitions shelf for artist’s books in the reading room. Stop by and unfold the layers of this (remarkably difficult to photograph) sculptural book called Fragments of Light 5 by Linda Schrank that features the poetry of Rumi translated by Partovi.

A generous donation from the Angora Ridge Foundation has made it possible for us to complete our collection of works from Vincent Fizgerald & Co., a New York based publisher founded in 1980 that produces limited edition artist’s books. Most of the works from this publisher are hand-printed with handset type, using handmade paper and images created through linocut, itaglio, lithography, silkscreen and photogravure. Several of the new aquisitions are available on our browseable new aquisitions shelf for artist’s books in the reading room. Stop by and unfold the layers of this (remarkably difficult to photograph) sculptural book called Fragments of Light 5 by Linda Schrank that features the poetry of Rumi translated by Partovi.