In 1931, Henry Zimmerman of Lone Tree, Iowa traveled to Kuznetsk, Siberia, to oversee the building of steel mills in the Soviet Union. The University of Iowa Special Collections has been collaborating with Russian History doctoral student Irina Rezhapova (Kuzbass Institute of the Federal Penal Service) on a special digital project which tells the story of Zimmerman’s journey. Special Collections will be making available online Henry Zimmerman’s personal letters and scrapbooks of photographs, news clippings and ephemera about his time in Soviet Siberia – all part of our Records of the Zimmerman Steel Company (http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/spec-coll/MSC/ToMsC900/MsC850/zimmermansteelworks.html).

This is Entry 2 of 3 of the Zimmerman Steel Journey.

“Foreign Specialists” in the Soviet Union: Exchanges of Technology and Work Ethic

The kinds of exchanges that took place in Siberia between the “foreign specialists” – experts from the US, Germany, Italy, France, Austria and Romania – and the Soviet workers, servants and administrators involved much more than one-way technology transfer. Planning and working side by side, steel experts from these countries also exchanged ideas and attitudes about labor. Thus Henry Zimmerman, who probably brought with him a strong individualist American work ethic which he acquired from his father’s business and other US companies, was now exposed to a Soviet work ethic that emphasized labor as an achievement and sacrifice for the collective: the ruling Communist Party and the future of Communism in Russia. In this Soviet work ethic, the individual’s achievement was valued not in its own right, but as another example of the supremacy of the working class of the Soviet people, and of Communism as a political and economic system. Soviet mines, factories and steel plants organized “socialist competitions” between working brigades in making bricks, loading coal, completing buildings or molding steel in larger quantities or well ahead of their original deadlines. The winners of such competitions received awards such as the designation “foremost worker,” vacations, and appearances at national holidays, political parades and historical commemorations.

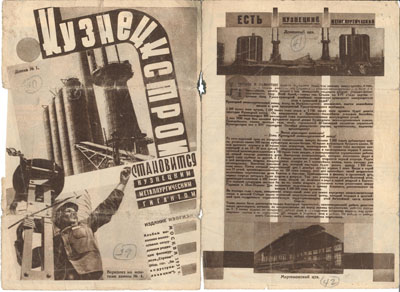

Even without being able to read Russian, we can see that the images in this 1932 article were posed to make Soviet workers appear heroic people who move mountains in building a robust new industry out of nothing for the glory of the Soviet Union.

Pages from a Russian magazine article about the construction of the steel mills in 1932

Was there harmony in the workplace between American engineers and Russian workers?

Hardly. In addition to the harsh weather and the differences in work ethic, Western specialists like Henry Zimmerman also faced professional rivalry from Soviet engineers and workers, who had strong national and occupational pride. “The Russian engineers insisted that they could do the various jobs themselves. They refused to follow our instructions. We pulled off of one job because of this, and they went ahead and caused an accident that killed 32 men. [….] We later organized our own bunch to keep the Russians out of our hair. All our recommendations were typewritten, and they stuck their necks out if they didn’t follow them. We got good cooperation from the [Soviet] government.” (“Personality Profile: Ageless Wizard is still Going Strong,” by Jim Arpy, Sunday Times-Democrat July 26, 1964)

Did the Soviets try to convert the Americans to Communism?

You bet! The Soviet leadership not only wanted to acquire technological expertise from the Western advisers, but they also wanted to educate their guests in the ideology of Marxism – hoping to convert them to the Soviet political and economic system. Accordingly, Russian officials included Communist propaganda in their briefings and lectures for Western advisers, as well as Russian language courses and group discussions of technology and life in the Soviet Union.

Were U.S. and other Western specialists successfully indoctrinated with Communist ideology? Even Russian researchers are doubtful about the outcome. “[Western experts] had a double attitude towards political messages: some were listened to, especially if reports were read in their native language, but others were ignored.” (O.A. Belousova, “Foreign Experts and the Soviet Reality: Life of the First Kuznetsk Builders.” 2003, translation by Irina Rezhapova) Do you think that they managed to convince Henry Zimmerman that Communism was the best political and economic system?

Please check our blog for the first and the third entry of the Zimmerman Steel Journey.

By Gyorgy “George” Toth, PhD Candidate in American Studies, Olson Fellow, The University of Iowa Special Collections & University Archives,

With

Irina Rezhapova, PhD Candidate, Russian History, Kuzbass Institute of the Federal Penal Service