By Hannah Hacker

Dracula has been a name that has instilled fear and fascination in the imaginations of readers and viewers since its original publication by Bram Stoker in 1897. There have been many adaptations and remakes of the novel since then, including F.W. Murnau’s silent film Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Graunens, the 1931 Universal Studios version of Dracula starring Bela Lugosi, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula starring Gary Oldman and directed by Francis Ford Coppola in 1992.

There was even a play adaptation about the captivating vampire. In 1924, Hamilton Deane adapted Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula into a stage play with the permission of Stoker’s widow. The play toured in England and was brought to Broadway in 1927.

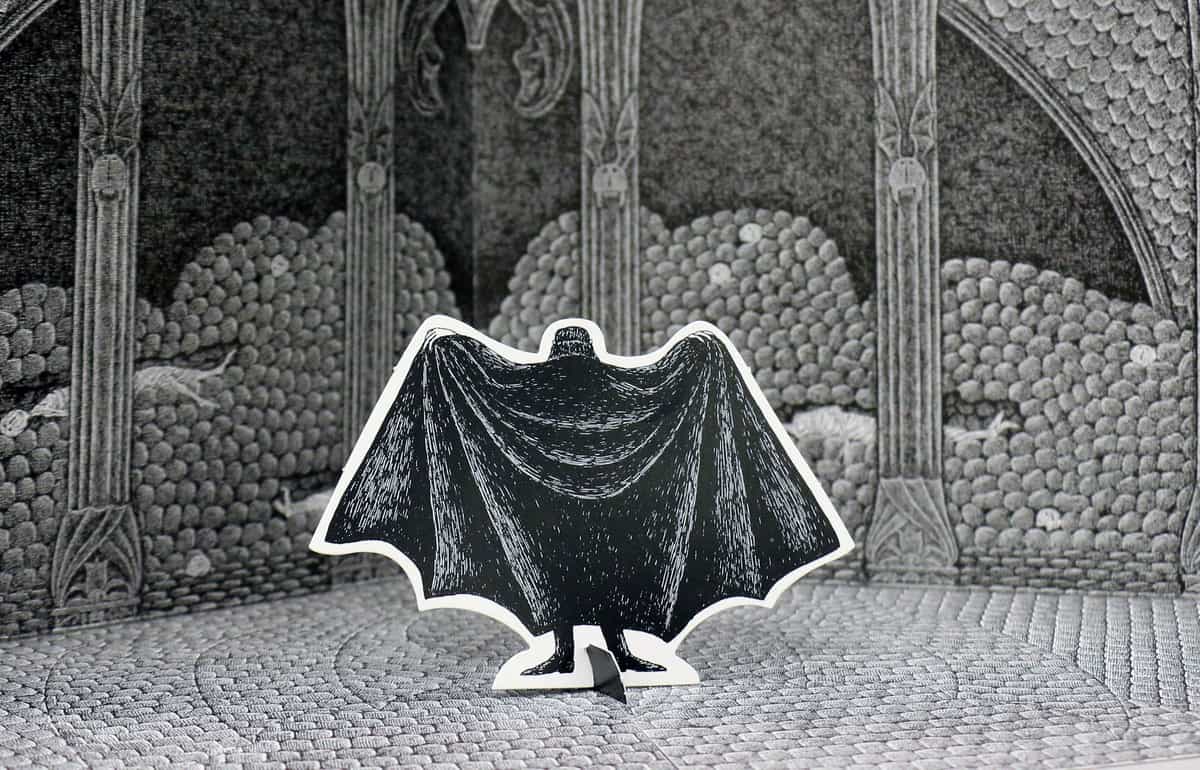

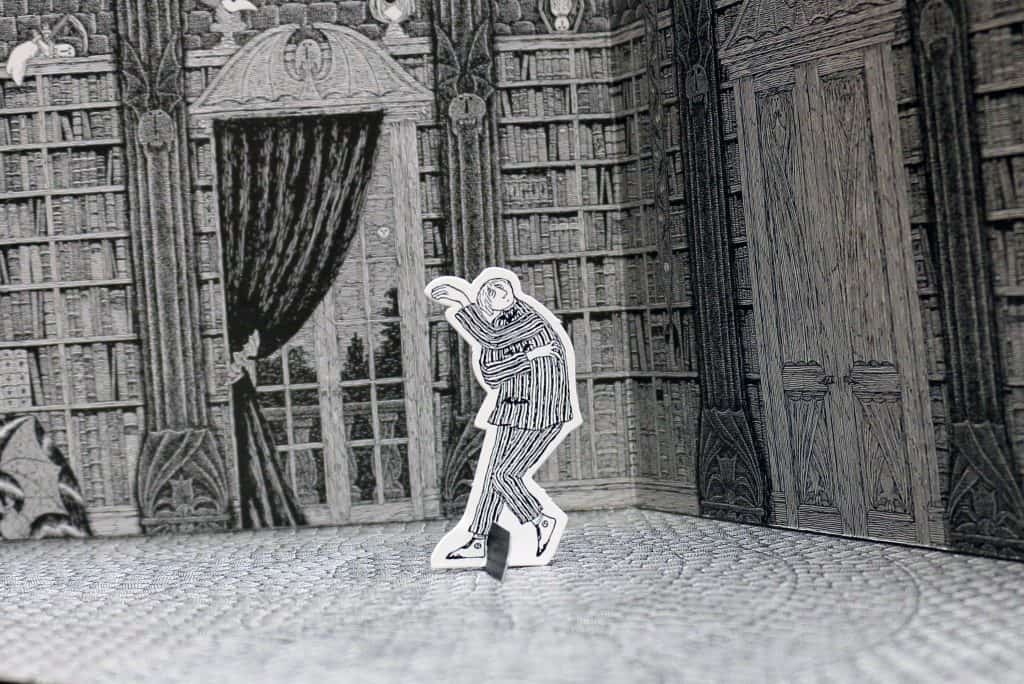

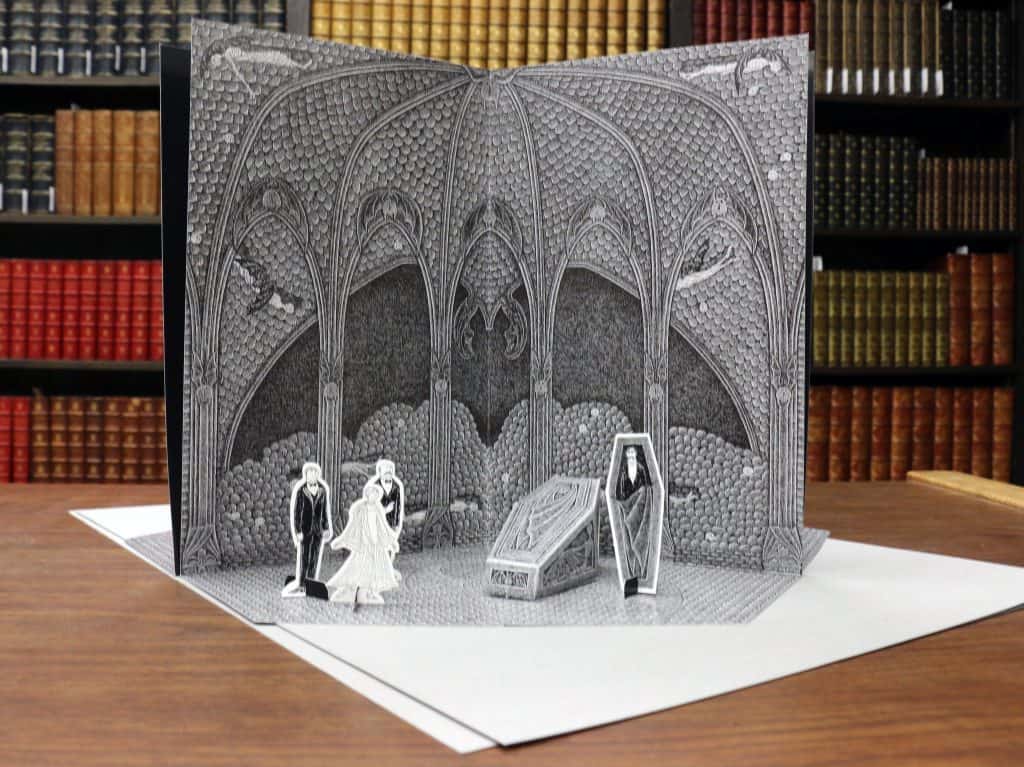

Dracula was revived in 1977 under the direction of Dennis Rosa. Sets and costumes were designed by Edward Gorey, who is well-known for his quirky cat drawings on T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats and other Gothic illustrations that have graced the covers of numerous classics, poetry books, and various other publications. With the set and costume design for Dracula, Gorey channeled his obsession with bats. Bats can be found in the walls, in the cobblestone, in the furniture – there are even bats incorporated into the characters’ clothing, like Renfield’s bat-buttoned pajamas.

The set and costumes were so enthralling that the play soon became known as “Edward Gorey’s production of Dracula,” instead of being fully credited to the director. Gorey’s designs were nominated for Tony Awards, and the production received a Tony in 1977 for the best revival of a play.

Dracula closed in 1980 after a strong run of 925 performances.

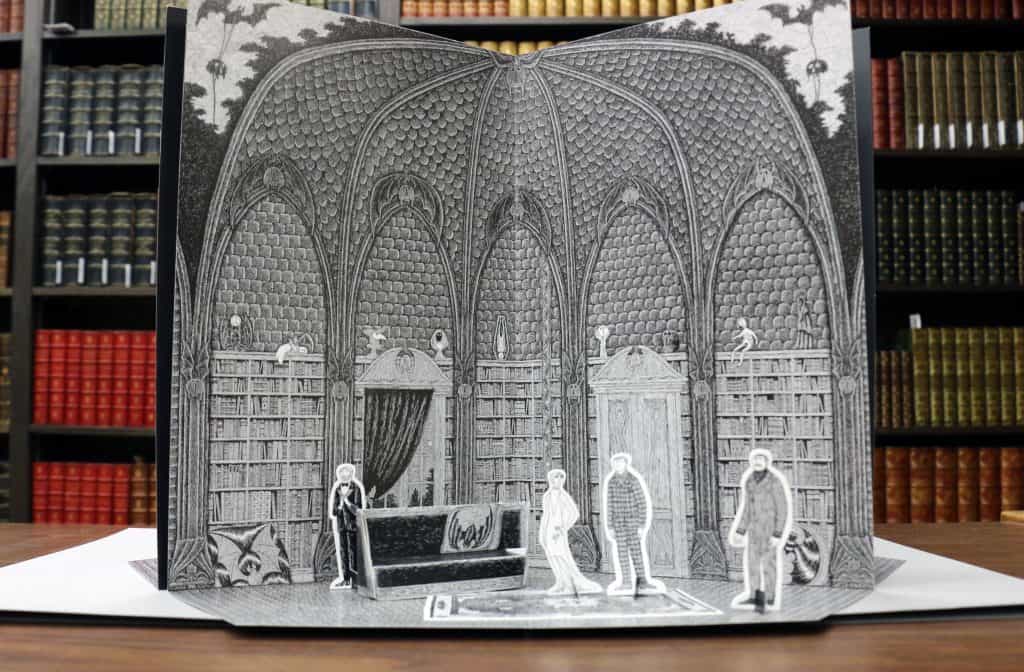

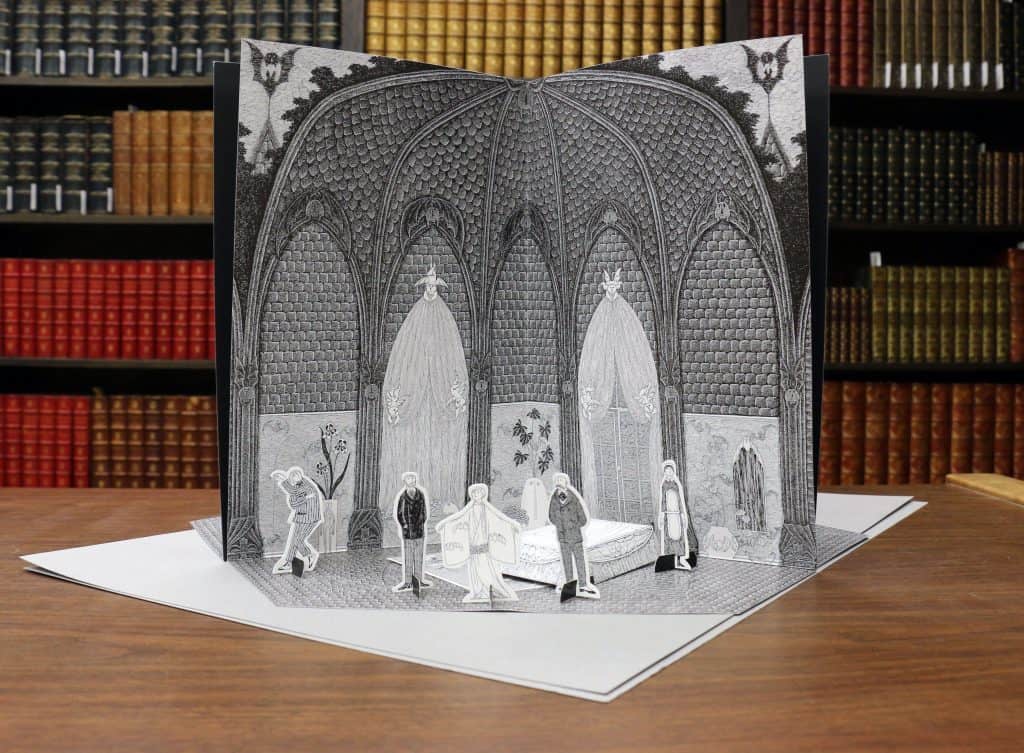

Edward Gorey’s vision of Dracula did not die with the close of the play. The designs rose once again in 1979 when Scribner’s published them as a spiral-bound book called Dracula: A Toy Theatre. The book contains Gorey’s original designs of the sets and characters, as well as a synopsis of the characters, scenes, and acts. The images of the characters, furniture, and set could be cut out from the pages and taped together so the reader could create their own interactive version of the original stage.

More recently, Pomegranate Communications picked up the book and made it into a box set of the toy theater with loose leaves of die-cut fold-ups and fold-outs. Once the theatre is constructed, the reader can have a full 3-D model of all three acts of the play.

Here at the University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections, we not only have a copy of Scribner’s publication of Dracula: A Toy Theatre, but two copies of the Pomegranate publication as well.

If you want to see them in person, you can swing on by to the Special Collections on the third floor of the Main Library. Otherwise, on October 28th, 11:00am – 3:00pm, we will be hosting a Halloween Pop-Up Exhibit on the first floor of the Main Library, where the complete construction of Dracula: A Toy Theatre will be the star of the exhibit, along with a showcase of some of our spookiest comics and fanzines.

Read more about the event at the link below, and we hope to see you there!

A ‘Gorey’ Good Time: Pop Up Exhibit

Works Cited

“Dracula (1924 Play).” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2016.

“Dracula (1977 Play).” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2016.

“Dracula.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 19 Oct. 2016.

Miller, Patrice. “Bat Ambassador: Edward Gorey.” The Edward Gorey House. Edward Gorey House, n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2016.

Popova, Maria. “When Edward Gorey Illustrated Dracula: Two Masters of the Macabre, Together.” Brain Pickings. Brain Pickings, 17 Sept. 2015. Web. 19 Oct. 2016.