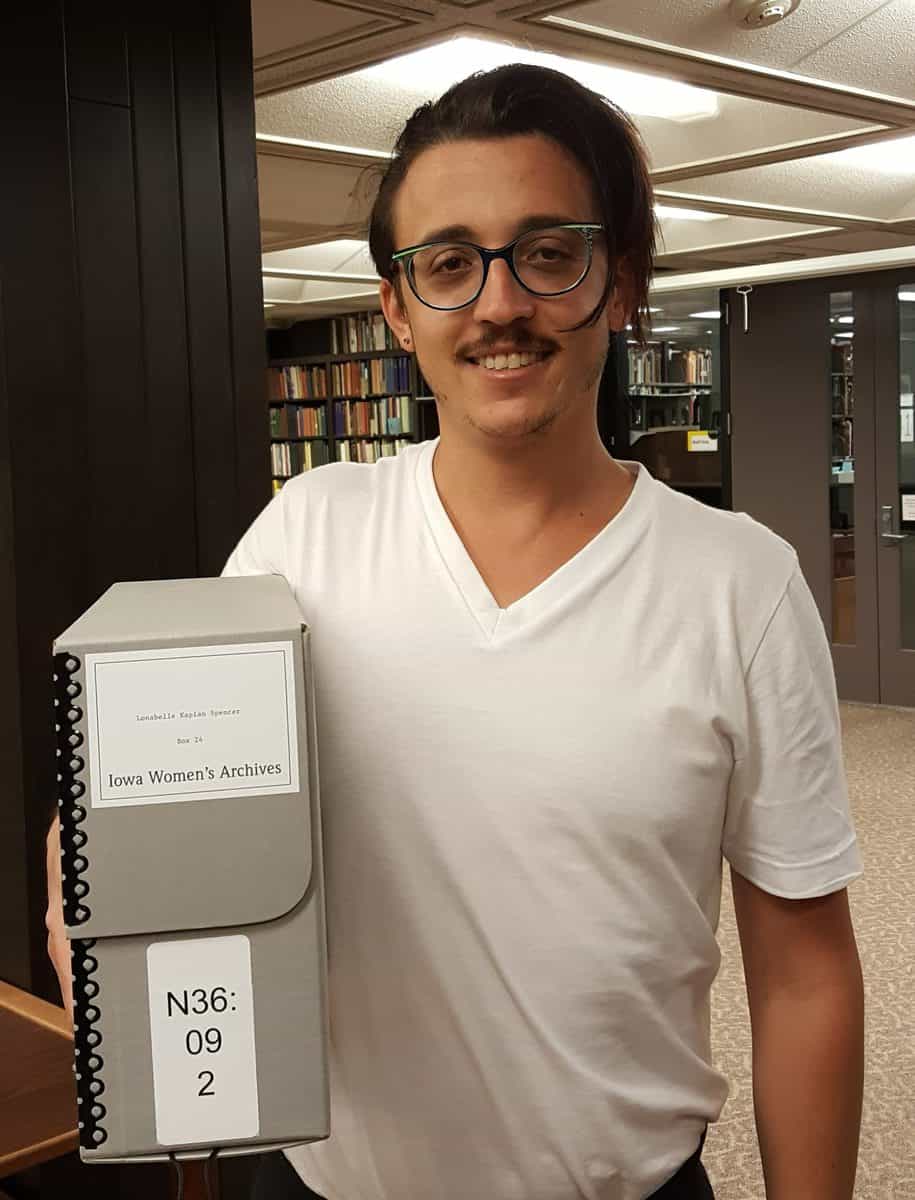

In Box 24 of the Lonabelle Kaplan Spencer papers, Andrew Seber finally found exactly what he was looking for: personal testimonies by rural citizens whose lives were turned upside down by the development of hog confinements near their Iowa homes. Seber’s dissertation, Neither Factory nor Farm: the Other Environmental Movement, will focus on industrial animal agriculture in Iowa, one of the world’s largest hog producers. As 2021’s Linda and Richard Kerber Travel Grant recipient, Seber was able to travel from the University of Chicago, where he is a doctoral student, to Iowa City and spend a week researching at the Iowa Women’s Archives.

Seber traces his interest in meat production back to high school, when an AP environmental science course first made him aware of meat as an environmental problem. He took this interest to college where he developed a scholarly interest in agriculture, ecology, and cultural studies. He believes that historically, the environmental movement has marginalized animal agriculture as a focus, in favor of fossil fuels and conservation. While recognizing that these are important issues, Seber says the irony is that animal agriculture is inextricably linked to both of them as it uses tremendous amounts of fossil fuel and causes air and water pollution. In his opinion, it cannot afford to be neglected, and he sees his work as a critique of the liberal environmental movement that became predominant in the 1970s and which informed the environmental social sciences.

For his research in IWA, Seber is relying heavily on the Lonabelle Kaplan Spencer papers to help him situate his work geographically. Spencer became an activist against Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) in the 1970s when she learned that a hog lot was being built near a Girl Scout camp. Through her work, she discovered that hog confinement was more than an odor problem. It affected property values, poisoned ground water, polluted air, and overall amounted to a new health hazard for rural residents. This is where Seber’s favorite box 24 of the collection comes into play. Spencer built a network of Iowans experiencing this pollution and a network of scientists studying it. She lobbied for regulations that would limit hog odor and animal waste; her efforts were mostly unsuccessful.

Seber says Spencer’s 1970s activism is part of a larger pattern that tends to go in cycles. In the 1970s and 1990s there were movements that really pushed for regulations on CAFOS. He’s found similar headlines in both eras and similar outcomes. He posits that this is partly due to neoliberal businesses that capture the process when activists try to use, as Spencer did, government hearings and studies to build their cases. But this isn’t the only problem, in some cases hog manure storage needs increase more quickly than regulations can keep up with, and some people still don’t view agriculture as an industry, which thwarts regulatory efforts.

After his fruitful research in Iowa, Seber will work on writing his next chapter, tentatively called “A Plain Old Cesspool: Concentrating Animal Life in Neoliberal Iowa,” and then turn his focus to North Carolina, another state with large scale hog operations. He hopes to complete his dissertation and degree in 2023.

Are you interested in applying for the Linda and Richard Kerber Fund for Research in the Iowa Women’s Archives? We will be accepting applications again next spring. You can keep tabs on the deadline and learn more on our website.