This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the third installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collection. The series will continue weekly during Black History Month, and monthly for the remainder of 2020.

If you’re looking for a local history of civil rights activism, look no further than The Iowa Women’s Archives, where our stacks are filled with the papers and records of remarkable individuals and organizations devoted to the ongoing struggle for civil rights and social justice – the Virginia Harper papers are one such collection. Harper was born in Fort Madison, Iowa in 1929. She studied at the State University of Iowa (now the University of Iowa) and was one of five African American women to integrate the first residence hall on campus (Currier Hall) in 1946. Harper worked as an x-ray technician and medical assistant in her family’s Fort Madison clinic and was actively engaged in her community, serving on the state Board of Public Instruction, the Iowa Board of Parole, and as Secretary and then President of the Fort Madison branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from the 1960s through the 1990s.

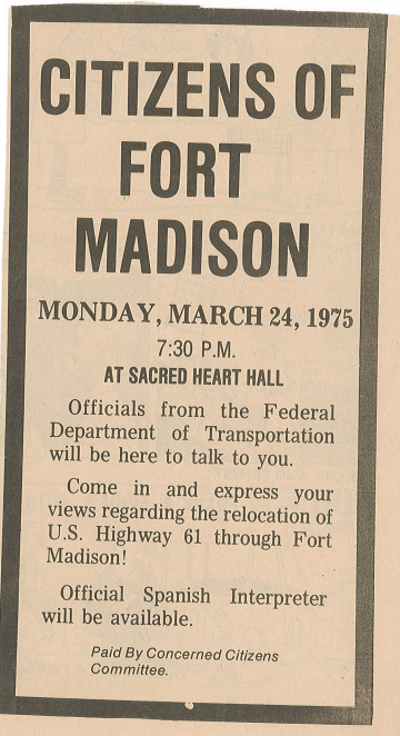

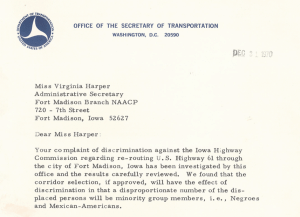

As NAACP Secretary, Virginia Harper took on local issues with national import. Beginning in 1967, the Iowa Department of Transportation (DOT) and Iowa State Highway Commission endorsed a plan to improve U.S. 61 in Fort Madison by re-routing the highway through the southwest corner of the city. These plans were meant to improve traffic conditions and ease of access to the city, but at the expense of the effected neighborhood, whose residents would be forced to relocate. The area in question represented what Virginia Harper called “the only truly multi-ethnic area in the city,” home to a significant number of African Americans, Mexican Americans, and low-income whites. Acting as Secretary of the Fort Madison branch of the NAACP, Harper filed a legal complaint against the project, alleging that it violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act because a disproportionate number of those who would be displaced were members of the minority population. This was the beginning of a struggle that went on for several years as Harper and others joined forces with leaders of the Mexican-American community to protest the plan, gather signatures for multiple petition campaigns, and correspond with various government agencies and national civil rights groups.

At the heart of Harper’s analysis was a critique of the racist and classist views which deemed this area of the city worth sacrificing. In a letter to the Department of Transportation on June 30, 1970, Harper outlined fourteen reasons why the relocation plan was objectionable. She wrote, “The corridor which has been chosen for the Highway relocation, follows the tradition of disrupting minority group neighborhoods. … Chosen because it is the ‘cheapest’ area of the town, it is this way because the citizens of this area have been systematically denied the privilege of living in other areas of the community.” In a letter to the editor of the Evening Democrat, Harper added, “This is not quite the time for sitting back and telling minority group members and lower income whites that they must sacrifice for the good of society. They’ve been sacrificing all their lives and are accustomed to being used.”

Part of a larger series on “Iowa Racial Issues,” the Highway 61 material in Virginia Harper’s papers provides insight into historic patterns and practices of redlining and defacto segregation in Iowa. Come to the archives to learn more about Harper and civil rights struggles in the state.

For more information on this topic, check out Kara Mollano’s article about Highway 61 in the Annals of Iowa: “Race, Roads, and Right-of-Way: A Campaign to Block Highway Construction in Fort Madison, 1967-1976.” The Annals of Iowa, Vol. 68, No. 3 (Summer 2009): 255-297.