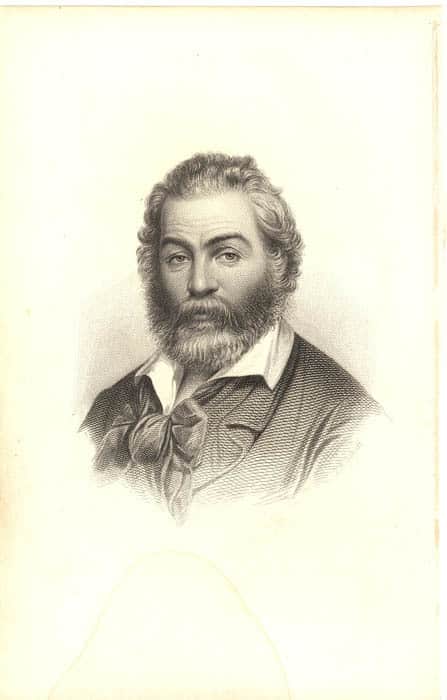

In the third open-access issue of the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review (WWQR) Editor Ed Folsom and Managing Editor Stefan Schöberlein publish in full a newly discovered book-length work by the poet Walt Whitman entitled “Manly Health and Training.” Zachary Turpin, a PhD candidate in English at the University of Houston, recently discovered “Manly Health and Training,” a previously unknown thirteen-part journalistic series of 47,000 words that originally appeared in the New York Atlas in 1858. Turpin’s important find means that “Manly Health and Training” can now be republished and confidently attributed to Whitman for the first time since 1858. As Turpin points out in the detailed introduction that accompanies “Manly Health and Training” in WWQR, surviving issues of the Atlas are rare today, even on microfilm, and he used one of the few remaining reels containing the newspaper, currently held by the American Antiquarian Society, to find “Manly Health and Training.” The byline for each of the installments lists the author as “Mose Velsor of Brooklyn,” a pen name that Whitman was known to have used occasionally for newspaper articles, and some of the articles from the “Manly Health” series also correspond in subject matter and/or wording with selections from Whitman’s notes on health and the body.

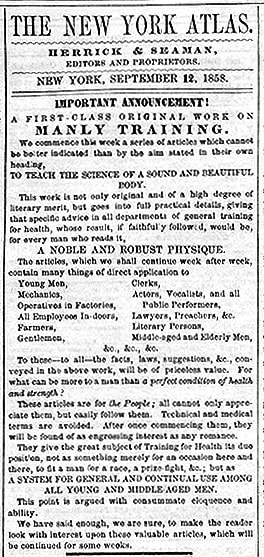

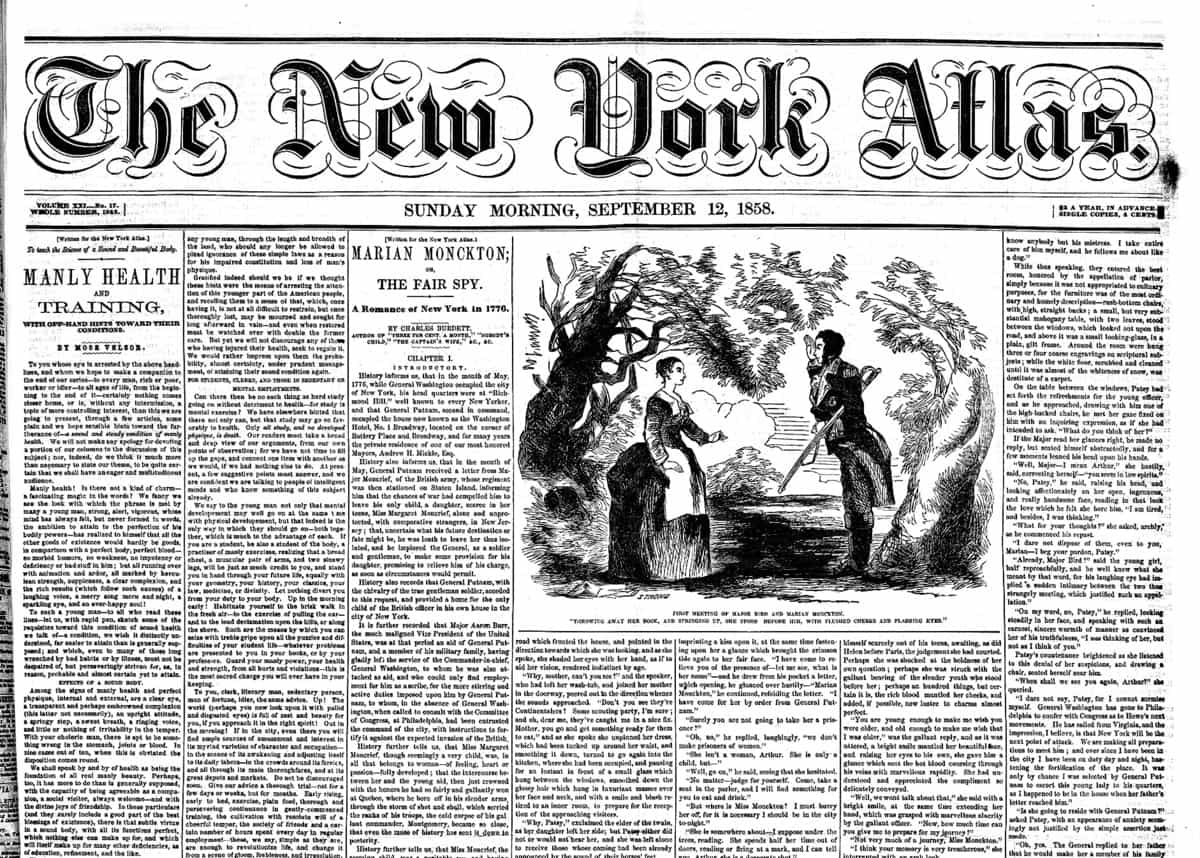

“Manly Health and Training,” which Turpin describes as a long lost “guide to living healthily in America,” stands as a remarkably significant new find. The articles promise to help fill in substantial gaps in the poet’s biography and to change the way we understand Whitman’s writings from this period. “Manly Health and Training” ran in the Atlas beginning on September 12, 1858, and ending the day after Christmas, December 26, 1858. This is approximately two years after the publication of the second edition of Leaves of Grass (1856) by Fowler and Wells—a Brooklyn publishing firm known for their texts on phrenology and physiognomy—and two years before the much-expanded third edition of Leaves of Grass (1860) that saw the addition of the “Calamus” and “Enfans d’Adam” (“Children of Adam”) poems on homoerotic and heterosexual love, respectively. In addition to being published between these two volumes of Leaves of Grass, “Manly Health and Training” (1858) was printed at nearly the same time as Whitman is believed to have been working on a twelve-poem sequence about love between men that he titled “Live Oak, with Moss,” which would become the core of “Calamus.”

In order to create “Manly Love and Training,” according to Turpin, Whitman drew on a number of sources ranging from temperance periodicals to works on science and pseudoscience of the period. The series of articles are shaped by many identifiable aspects of nineteenth-century culture including such topics as phrenology, eugenics, male friendship, sports and sports figures, lecture and oratory, vegetarianism, and other social reform and self-help literature. The articles are remarkable, then, for their wide array of content, but they are equally surprising for what is largely absent: the topics of women’s bodies, health, and training. Such an absence, while perhaps not entirely unexpected, merits further investigation given that on September 16, 1888, Whitman told his friend Horace Traubel that women were among his “sturdiest defenders, upholders” and that Leaves of Grass was “essentially a woman’s book.”

Turpin’s discovery of Whitman’s “Manly Health and Training” will certainly shed new light on the poet’s activities in the years following the publication of the articles and leading up to and continuing through the Civil War. If, for example, Whitman advocated a training program that involved exercise and a healthy diet, then why did he choose to spend so much of his time in 1859 and the early 1860s at Pfaff’s, a New York beer cellar and popular American Bohemian hangout, known for its coffee, lager beer, and wine selection, as well as its substantial food offerings? How does Whitman’s interest in leading American men toward sound, muscular, and virile bodies change the way we view Whitman’s seeming need to volunteer in the hospitals of the Civil War, where he would have seen first-hand the devastating injuries—the gaping wounds—in those very bodies he was seeking to guide toward a state of “perfect health”? And what does Whitman’s insistence that the very act of reading is not a “half-sleep” but rather a “gymnast’s struggle” mean for us, as readers of his works, in light of “Manly Health and Training,” with its assessment of prize-fighting and advocacy of exercise?

With the publication of “Manly Health and Training” in WWQR, we can begin to answer these questions and, no doubt, to formulate many others. But Turpin’s find, 158 years after the original publication of Whitman’s articles, should also draw our attention to the fact that even when it comes to well-known authors like Whitman, much remains to be discovered. This is likely true, not just of Whitman, but of many other nineteenth-century writers when our research includes newspapers and magazines. Examining periodicals in print and digital forms, as well as archival research in general, has yielded significant finds in the field of Whitman Studies over the past several years. A new Whitman poem, as well as numerous reprints of his short fiction and reprints of his poetry in periodicals have come to light, and, recently, a letter Whitman wrote for a Civil War Soldier was discovered in the National Archives. Turpin’s find also serves to remind researchers that not all newspapers and magazines from the past are digitized, available, and easily searchable online. In fact, many periodicals are still available only on microfilm and/or in print form. The discoveries we make in the future, then, will depend a great deal on where we look and how we preserve and use archival material in all formats.

Finally, the publication of “Manly Health and Training” in its entirety in the current WWQR is a noteworthy feat in itself. In October 2015, during open-access week, WWQR, a University of Iowa journal and the international journal of record in Whitman Studies, made the transition from a print journal to an online only, open-access publication with the help and support of the Digital Scholarship and Publishing Studio at the University of Iowa Libraries. This online format, as the editors of the journal make clear in their foreword to the issue, has made possible the publication in full of Whitman’s “Manly Health and Training.” In the journal’s previous print version, printing costs and page limits would have necessitated the careful selection of only a few excerpts from this previously unknown text. One of the many benefits of offering a scholarly journal as an online and open-access resource is that this digital format opens up a range of publishing options and formats not possible in print alone. As a result, the editors can share this newly discovered piece of the poet’s writing with an ever-growing international body of Whitman readers who access his writings via an internet connection. In the future, “Manly Health and Training” will also be available on the Walt Whitman Archive. If, as Whitman wrote in his advertisement for “Manly Health and Training,” he intended this text “for the People,” he almost certainly would have approved. It is my hope that all readers of “Manly Health and Training” will actively engage and even struggle with this piece as Whitman recommended, since it remains for us–the readers–to investigate how Whitman came to write this piece, to trace the origins of these ideas, and to determine how we, in coming to this text some 158 years after its first publication, might make use of it in our own time and in our own ways.

Stephanie M. Blalock

Digital Humanities Librarian &

Associate Editor, Walt Whitman Archive

University of Iowa Libraries