Zachary Turpin, a PhD candidate in English at the University of Houston (who made international headlines in April 2016 with his discovery of a previously unknown journalistic series by the poet Walt Whitman entitled “Manly Health and Training”) has made another major find: a long-lost, secret novella, also authored by Whitman, entitled Life and Adventures of Jack Engle: an Auto-Biography (A Story of New York at the Present Time). Totaling about 36,000 words, Jack Engle, was published anonymously as a work of serial fiction in six installments in 1852 in the New York Sunday Dispatch, a weekly newspaper edited by Amor J. Williamson and William Burns that regularly published works of serial fiction. Turpin’s incredible find means that Jack Engle, a novella that Whitman never talked about and that no one knew he had written, can now be republished for the first time since 1852 and confidently attributed to Whitman for the first time ever. In the current issue of the online, open access Walt Whitman Quarterly Review (WWQR), Editor Ed Folsom and Managing Editor Stefan Schöberlein have published Jack Engle in full, and the 150-page journal issue also includes an essential and substantial scholarly introduction by Turpin. The University of Iowa Press collaborated with Turpin and the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review to publish a print edition of Jack Engle, including an introduction by Turpin. Hardback and paperback copies of the novel are now available for purchase on the University of Iowa Press website.

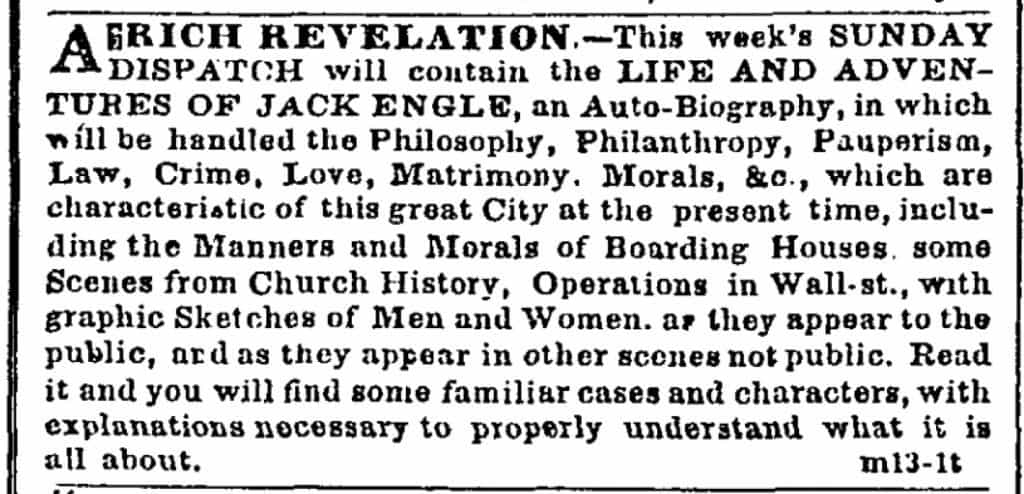

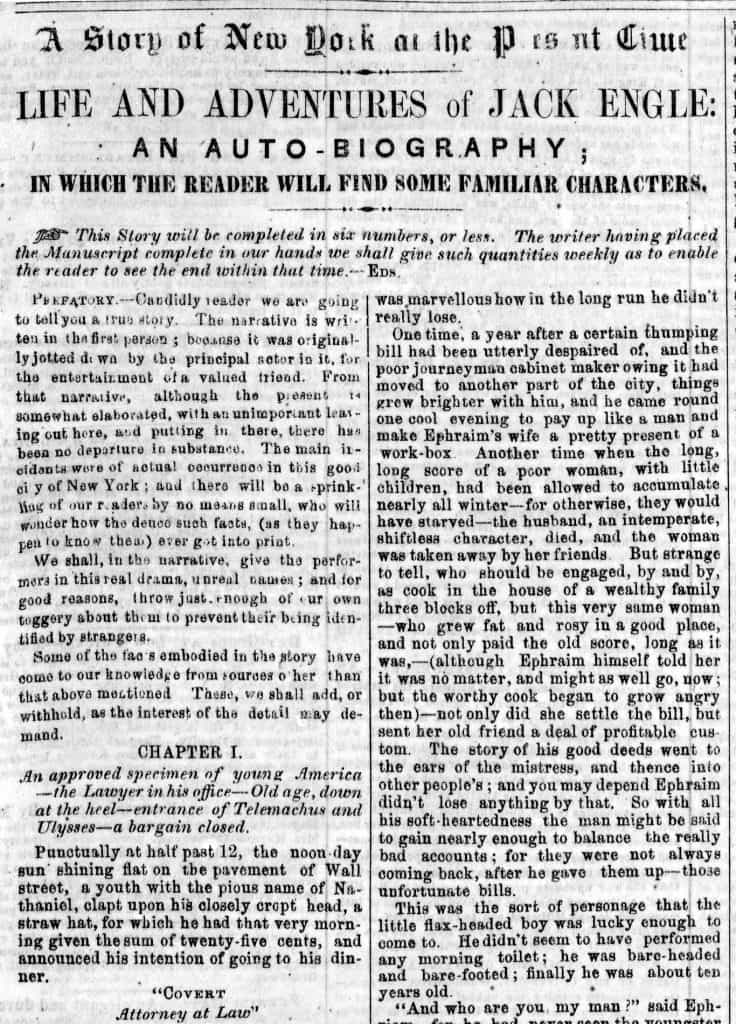

Although the publication of Jack Engle today will certainly receive national and international media attention, its appearance in 1852 was barely advertised, and, as far as we know, there were no reviews of the novella and no other responses from newspaper readers. On March 13, 1852, the day before Jack Engle began its run in the Dispatch, a brief and unremarkable literary notice for the novella was published in three New York newspapers: the Tribune, the Herald, and the Daily Times. The notice promised readers that the following day, the Dispatch would begin publishing the Life and Adventures of Jack Engle, an Auto-Biography, a novella praised in the notice as “A Rich Revelation,” that would deal with “the Philosophy, Philanthropy, Pauperism, Law, Crime, Love, Matrimony, Morals, &c., which are characteristic of this great city at the present time.”

This new work of fiction would be printed over the next month from March 14 to April 18, 1852, with a few chapters appearing each week. As Turpin points out in his beautifully written and informative introduction, the novella ran without a byline, and there were no additional advertisements or notices. This is especially striking because Whitman had been a successful fiction writer throughout much of the 1840s. In fact, by 1852 he had published at least 26 short stories, and several of them had appeared in the Democratic Review, one of the era’s most prestigious magazines. He had also written a temperance novel, Franklin Evans, or the Inebriate, a Tale of the Times that had sold 20,000 copies–more than anything else Whitman would publish in his lifetime, including Leaves of Grass. It was only later that Whitman, then known primarily as a novelist and popular fiction writer, would become one of the nation’s favorite poets, and it took nearly 165 years after the original publication of Jack Engle for Turpin to discover the novella and prove conclusively that Whitman authored it.

Jack Engle, which Turpin describes as “a story of coincidence, adventure, and the incompatibility of love and greed” stands as a historic and incredibly important new find. According to University of Iowa Professor and Walt Whitman expert Ed Folsom, Jack Engle is a “momentous” find that “makes us rethink everything we thought we knew about Whitman’s fiction.” After all, it has long been believed that Whitman’s fiction career spanned only seven years–from the publication of his first short story “Death in the School-Room” in the Democratic Review in August 1841 until the printing of “The Shadow and the Light of a Young Man’s Soul” in the Union Magazine in June 1848. After this, Whitman was thought to have given up fiction writing for good and turned to composing poems–a puzzling career move given the success and widespread circulation of his earlier fiction. The publication of “Jack Engle” in 1852 offers evidence that Whitman did not make such a definitive transition from writing short stories to crafting poems with long, prose-like lines. Instead, he continued writing fiction at least into the early 1850s, which nearly coincides with the time he began working on the poems that would later appear in the first edition of Leaves of Grass, published in 1855. As Turpin puts it in his introduction, “Whitman did not give up but began again,” seemingly returning to novel-writing, while also drafting plot outlines and prose fragments. Because of Jack Engle, therefore, instead of seeing Whitman as a fiction writer abruptly shifting to poetry, scholars and readers alike must now imagine him as a writer of poetry and fiction for newspapers and magazines who was not yet sure what shape Leaves of Grass or even the next few years of his writing career would or should take.

Whitman has not traditionally been praised among scholars for his fiction writing ability. Thomas Brasher, editor of The Early Poems and the Fiction, a volume of the Collected Writings of Walt Whitman, said of the early stories that “Whitman had no talent for fiction,” while Emory Holloway, an early Whitman biographer, wrote that many of the poet’s early and melodramatic stories “deserved to die in the age of sighs that gave them birth.” Jack Engle stands in sharp contrast to Whitman’s early fiction even though it clearly drew from some of that writing. As Turpin points out in his introduction, Jack Engle is “some of the better fiction Whitman produced.” The plot and characters in this novella were clearly composed and sketched by a more mature Whitman; he was a far more experienced writer of newspaper fiction by 1852 than he had been when he wrote his short stories a decade earlier. According to Turpin, Whitman drew on several genres of popular fiction while writing Jack Engle, including “sentimentalism, sensationalism, adventure fiction, [and] reform literature,” among other genres. To this list, I would add detective and mystery fiction, as well as epistolary fiction given the number of texts–ranging from letters and wills to gravestones and prison narratives–that advance the central plot. By drawing on all of these genres, Whitman creates a novella that Turpin has called “Dickens Light” and that might also be described as a tale of corruption, misogyny, class division, religion, romance, and male friendship.

Jack Engle follows the adventures of a young orphan in New York who is adopted by Ephraim Foster, a milkman and “purveyor of pork and sausage” near the Bowery and his wife Violet, a woman Whitman describes as having the “breadth of a good sized man” and no knowledge of “what are now called Women’s Rights.” Ephraim urges young Jack to pursue the study of law, which Jack undertakes largely for the sake of pleasing his adoptive father. Soon Jack finds himself employed by “Mr. Covert,” a corrupt and greedy lawyer who “had among the forms of his selfishness, some political ambition.” Covert is also the guardian of a young woman named Martha, and he is constantly scheming to cheat Martha and other beneficiaries out of the inheritance left for them by her imprisoned and dying father. When Jack and Martha meet, they realize they are actually old acquaintances; they become fast friends once again, and Jack longs to help the unhappy young woman. Can Jack and Martha thwart Covert’s attempts to steal her inheritance? Even more importantly, will they be able to keep Martha from falling victim to the lawyer’s sinister and “licentious passions”? Will the identity of Jack Engle’s parents and his family history ever be revealed? The answers to these key questions and many more can only be found by reading the novella in full. Along the way, readers will meet numerous other odd and eccentric characters, including a dancing girl, several individuals of the Quaker faith, some law clerks (one of whom doubles as a detective), a series of night watchmen policing the boundaries of the city, and a dog that, oddly enough, is also called “Jack.” In order to learn the fate of Jack Engle and Martha, readers must follow the action of the story as it moves from a sausage vendor’s shop to the law offices and from the dancing girl’s home to the boat docks under the cover of darkness. The tale’s numerous mysteries are finally resolved and, at the end, the characters can begin to look forward to the future rather than back on their respective pasts.

Even though the air of mystery, the humor, and the impressive cast of characters set Jack Engle apart from Whitman’s earlier fiction, it is hard not to see some similarities between it and his previous writings. Much like the novella’s protagonist Jack Engle, the main characters of Whitman’s short story “The Love of the Four Students” are studying law under the guidance of a lawyer. The character of Violet Foster, Jack’s adoptive mother, is actually taken from “The Fireman’s Dream,” an unfinished piece of fiction that Whitman published in 1844 in the New York Sunday Times and Noah’s Weekly Messenger. Only two chapters of “The Fireman’s Dream” were ever published,” but the description of Violet in Jack Engle is taken, nearly verbatim, from the characterization of Violet Boanes in the earlier work. As Turpin also points out, the villainous lawyer “Mr. Covert” shares his name with an earlier character, “Adam Covert,” another evil lawyer who is murdered as a result of his scheming in “Revenge and Requital,” a tale that was published in 1845, seven years before Jack Engle.

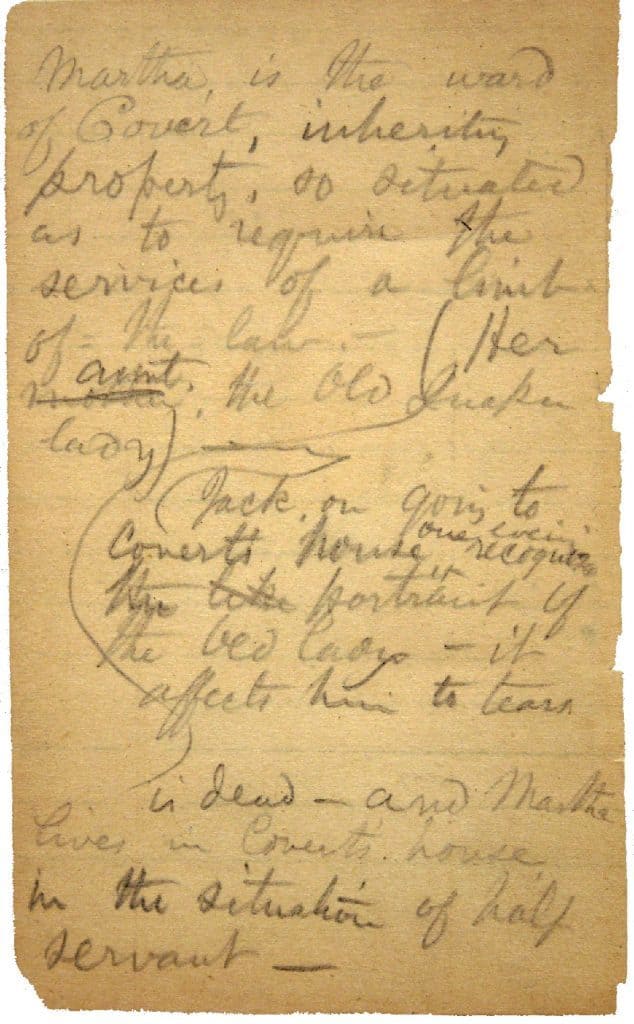

These connections to Whitman’s earlier fiction, combined with both the improved quality of the writing in Jack Engle and the previous success of Franklin Evans, make Whitman’s decision to publish the novella anonymously seem especially perplexing. It would have made sense, after all, for Whitman to attempt to capitalize on the sales figures of Franklin Evans by including his name in a byline with Jack Engle. At the same time, Whitman was not typically silent about the success of his fiction. He once bragged to the editor of the Boston Miscellany that his short stories had been reprinted frequently by newspapers and magazines all over the country, and he was right in his assessment of the widespread circulation of those stories. Even when Whitman attempted to distance himself from his novel and the short stories late in his life, he was particularly vocal in his dismissals of those early works. In 1882, Whitman wrote that he sincerely wished “all those crude and boyish pieces” of fiction he wrote in his youth would drop into “oblivion,” and in 1888 he reportedly referred to Franklin Evans as “damned rot.” But as far as we know he never mentioned Jack Engle at all. There is no known evidence that Whitman ever claimed it or disavowed it. He does not seem to have spoken about it–not even to his family or closest friends–and the only time he wrote about it might well have been the plot outline, including character names that he recorded in his schoolmaster notebook, the document that led Turpin to this amazing find.

Whitman’s silence on the subject of Jack Engle–save for the notes about the plot–certainly made Turpin’s work more challenging. But Turpin’s research methodology is worthy of note here because he was able to utilize and move between digital and archival (print) collections to make the find. While prose fragments are not necessarily unusual in Whitman Studies, long lists of plot events and the actions of individual characters are rare. Scholars have long been aware of the schoolmaster notebook and a plot outline that includes the name “Jack Engle,” among others from the novella. Turpin followed the sparse evidence from digitized images of the notebook pages to newspaper databases, where he encountered an announcement for the publication of a novella that promised to detail the life and adventures of “Jack Engle.” Turpin was able to confirm his discovery–matching the plot Whitman outlines to the events of the full novella–with the support of the English Department at the University of Houston and research assistance from the Library of Congress, which holds one of the only–if not the only–series of extant issues of the Sunday Dispatch that printed the installments of Jack Engle. In collaboration with the staff of the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, Turpin then transcribed and edited the novella for the journal and for the University of Iowa Press’s newly released print edition. With an open access (free) digital edition and a print edition of Jack Engle now available for purchase, the novella will certainly have a new life as readers and fans of Whitman examine this secret, long-lost novella for the first time. The very existence of Jack Engle also suggests that there may be more works of fiction by Whitman waiting to be discovered, and it is my sincere hope that many more rich revelations about the novella and about all of Whitman’s fiction will soon follow.

Stephanie M. Blalock

Digital Humanities Librarian &

Associate Editor, Walt Whitman Archive

(http://www.whitmanarchive.org/)

University of Iowa Libraries