The following is written by graduate student worker Sydnee Brown

It is usually a shock when we realize that famous historical figures and celebrities struggle with everyday things like chores or math and language homework. Well, what if we told you that the iconic Mary Shelley also struggled with learning a new language?

Mary Shelley, “The Mother of Sci-Fi” and renowned author of Frankenstein, was born in 1797 to Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, who were both known political philosophers in the latter half of the 18th century and early 19th century (de Bruin-Molé). Shelley, unfortunately, did not get to know her mother, as Wollstonecraft died of puerperal fever merely eleven days after giving birth. Godwin then took up the task of raising his and Wollstonecraft’s daughter, as well as Shelley’s five other siblings—all of whom were either illegitimate or siblings through marriage (Bennett).

Shelley was educated early on at both a dame-school as well as a short spell with Miss Caroline Petman at her school for daughters of dissenters. However, her primary educator was her father who prioritized his children’s education highly. Godwin nurtured the imaginative minds of his children, and he gave Shelley the skillset and conviction to be able to instigate change as an activist. He provided Shelley a well-rounded education in history, mythology, and literature—including the Bible. Not only was Shelley educated in English literature, but she was also tutored in several other languages, being fluent in both Italian and French, as well as Latin, Greek, and some Spanish. It has been said that, when she married Percy Bysshe Shelley, he tutored her in both Latin and Greek as well (Bennett).

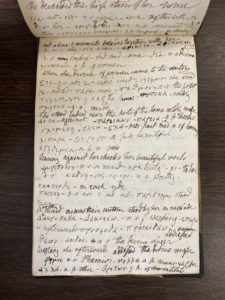

As a scholar in classical languages and mythology, it is no surprise that Shelley would have read from classical authors such as Homer. In the Leigh Hunt collection where we have an assortment of books and manuscripts by and about English writer James Henry Leigh Hunt, we have one of Shelley’s notebooks where she is working through translations in Ancient Greek (Leigh Hunt Collection, Ms S54G). In this notebook, Shelley is reading Homer’s Odyssey and working through a translation. She wrote down names of significant characters early on—Odysseus, Penelope, and Telemachus—and other line translations indicate that she was working through Book I, lines 114-387 (Bowers 514). This manuscript of Shelley’s has received very little critical attention—Will Bowers’ 2017 article appears to be the only comprehensive study done about the notebook.

While the majority of this notebook is dedicated to Shelley’s translations of Homer, there are also two pages containing an Italian transcription of Marco Lastri’s L’osservatore fiorentino sugli edifizi della sua patria (3rd edition 1821), specifically the section where he quotes Bendetto Varchi’s Storia fiorentino (Bowers 515). Though these transcriptions are interesting, Shelley’s Homer deserves a bit more scrutiny.

According to Bowers’ research, this notebook can be dated back to Shelley’s stay at Pisa from 1820-1822, where one of her primary tasks was to learn Greek. If she was dedicating two years of her life to the study of Ancient Greek, we can assume that she might not have been proficient in the language at this time.

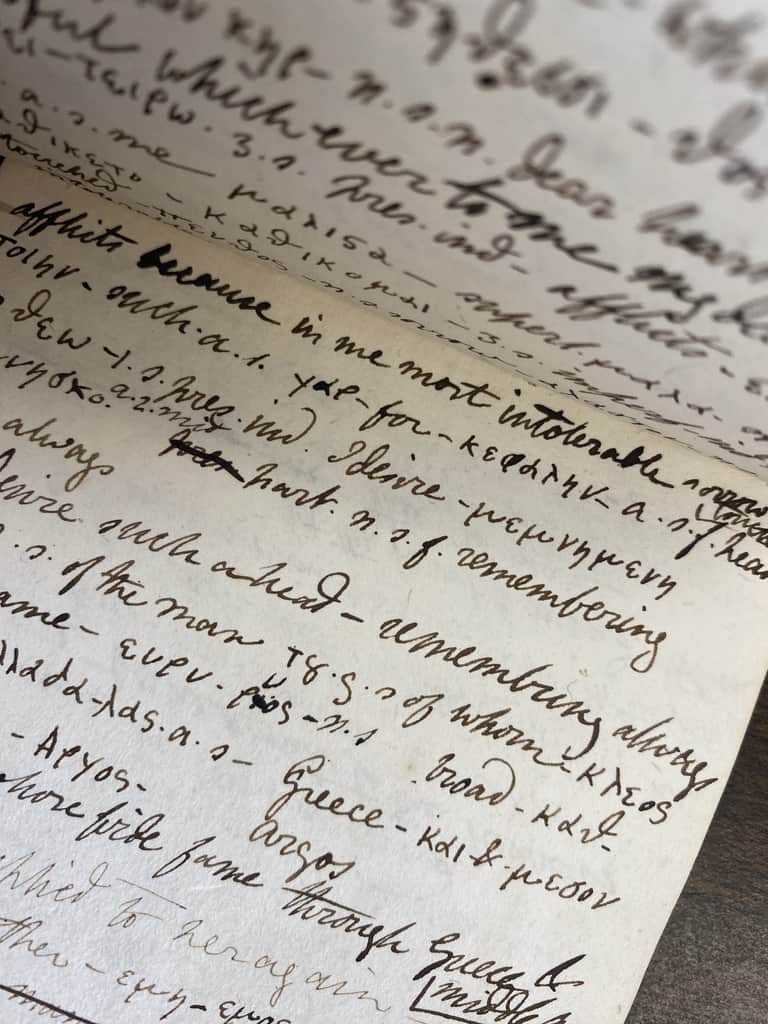

Looking at her notebook, she is working her way through the text as though she is either a beginner or, at the very least, she is struggling with Homer’s dialect. The pages of this notebook are filled with basic Greek words such as ουκ (not), παντας (all), γαρ (for), and διος (god/godlike). This vocabulary is taught to beginner Greek students early on, so it would not be a stretch to assume that Shelley was either a novice or struggling. However, it appears that she becomes more comfortable as she moves through the translations, only writing down difficult vocabulary or working through their grammatical peculiarities.

Along with her vocabulary glosses, Shelley also works through sentence structure in order to translate both full and partial lines of the Greek. She parses verbs and nouns to see how they grammatically work together in the sentence, such as “μεμνησκο a.2.mid part. n.s.f. remembering” in order to fully translate the sentence, “for I desire such ahead – remembring always.” From this moment, it is clear that she is attempting to reinforce grammatical concepts and better understand Homer’s Greek.

Shelley’s translation process throughout the notebook remains much the same, and it is intriguing to watch her learn and grow from a language-learning perspective. From her notes, she seems to be reinforcing her vocabulary and grammar knowledge, and she is consistent with her methods. While Mary Shelley might have been the master and mother of sci-fi, it doesn’t look like she was a master of Greek—at least, not yet.

Works Cited:

Bennett, Betty T. “Shelley [née Godwin], Mary Wollstonecraft (1797–1851), writer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 29. Oxford University Press. Date of access 4 Mar. 2023, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-25311

Bowers, Will. “On First Looking into Mary Shelley’s Homer.” The Review of English Studies, vol. 69, no. 290, 2017, pp. 510-531.

de Bruin-Molé, Megen. “‘Hail, Mary, the Mother of Science Fiction’: Popular Fictionalisations of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley in Film and Television, 1935–2018.” Science Fiction Film & Television, vol. 11, no. 2, June 2018, pp. 233–55. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.3828/sfftv.2018.17.