The following is written by Kathryn Reuter, Academic Outreach Coordinator for Special Collections & Archives and for Stanley Museum of Art

In 1938, Chester Carlson invented the process of electrophotographic printing. Later rebranded as xerography, this process is what fuels photocopy machines around the world. Carlson’s invention forever changed the nature of office work and schoolwork, but it also sparked creativity for artists around the globe. While many of us associate the Xerox machine with the monotony of paper pushing and working nine to five under office florescent lights, members of the International Society of Copier Artists (I.S.C.A.) saw the copy machine as an artist’s medium and eagerly embraced the possibilities of this tool.

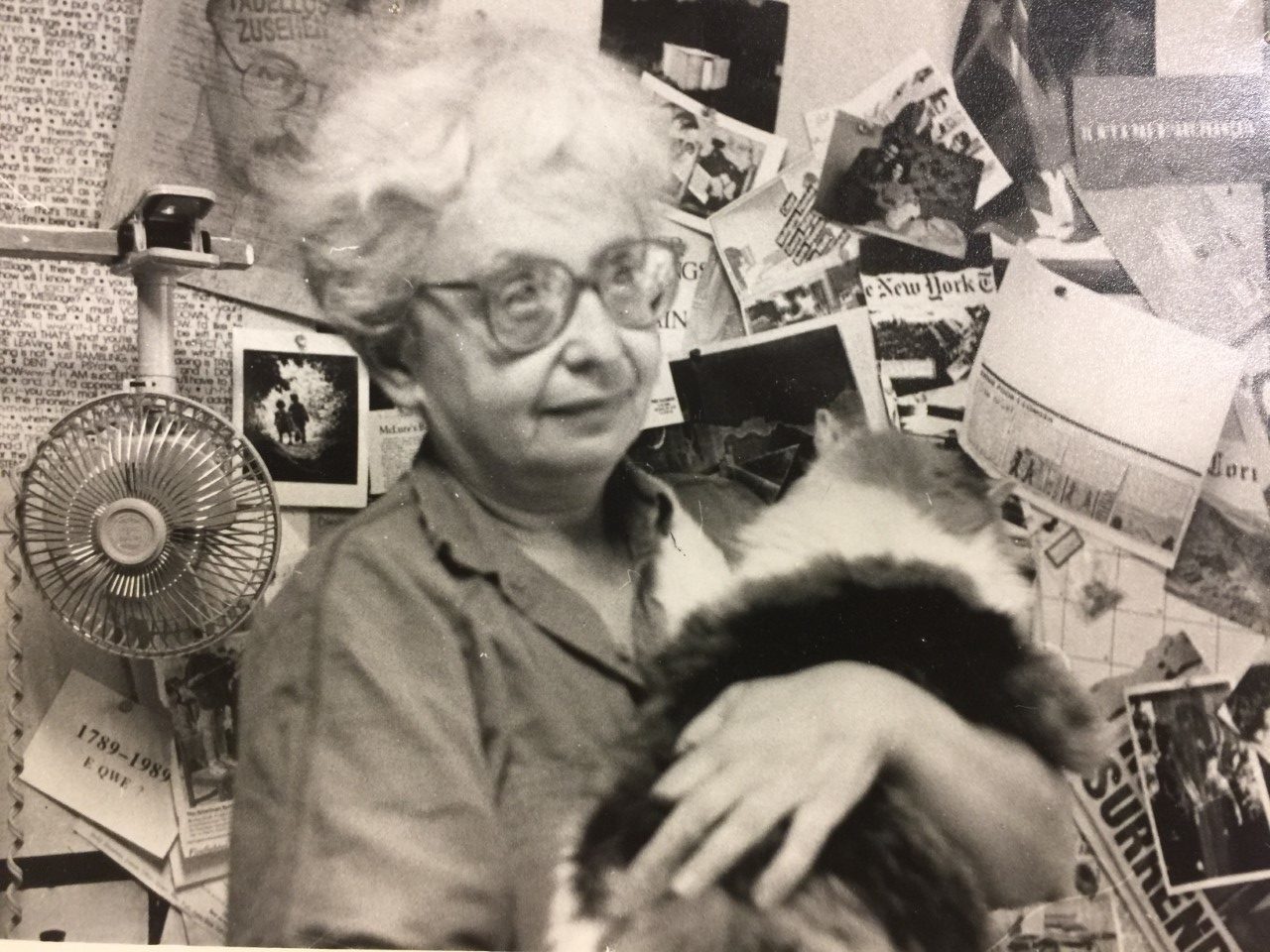

Louise Neaderland founded the I.S.C.A. in 1981 as “a non-profit professional organization composed of artists who use the copier both alone and in conjunction with other medium to create prints, murals, billboards, postcards and an innovative array of bookworks.” (I.S.C.A. Quarterly vol. 1 no.1, 1982) Neaderland is a printmaker, book artist, and alum of Bard College and the University of Iowa. Beginning in the early 1980s, her New York City studio became a hub of copier artist activity. Rather than gathering and sharing their work in person, artists corresponded with Neaderland primarily through the postal system. In addition to artists, membership in the I.S.C.A. was open to art collectors and institutions like libraries and archives.

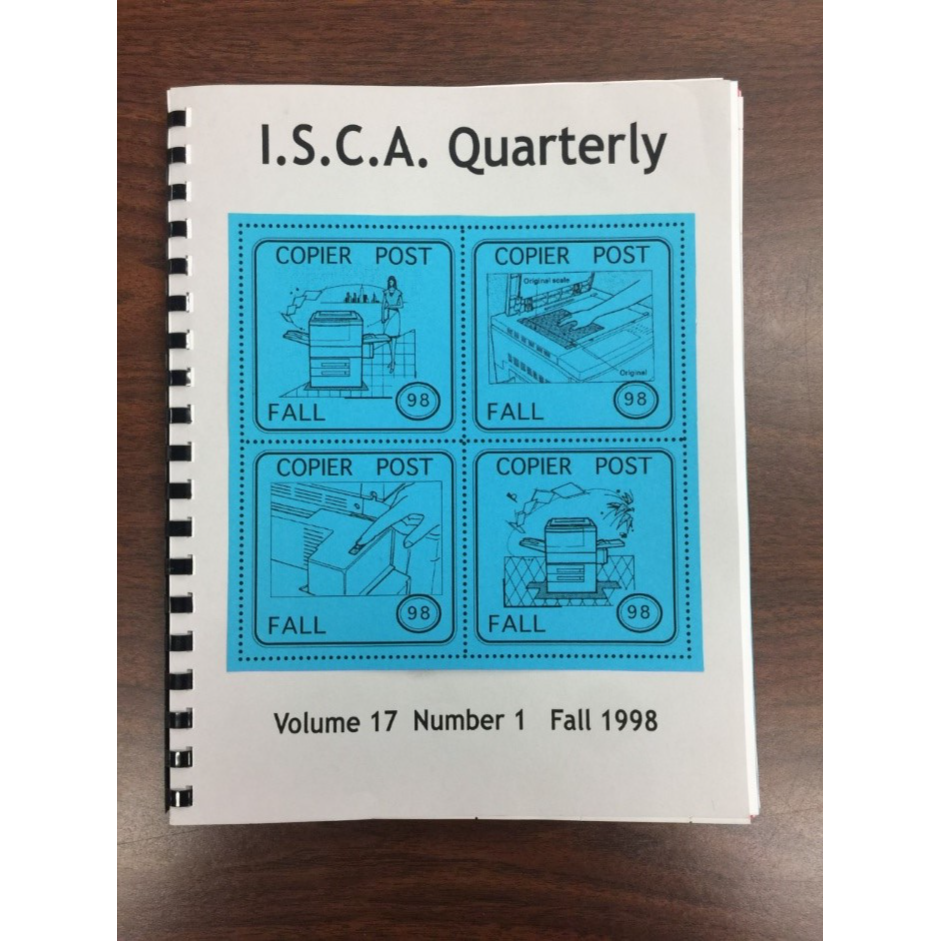

At the core of the I.S.C.A. was the I.S.C.A. Quarterly, a publication of work by member artists. Neaderland published the first volume of the I.S.C.A. Quarterly in April of 1982, and aside from the occasional guest editor, it appears that the operation was largely a one-woman show. Artists would mail copies of their work to Neaderland, who would organize the submissions and publish the pieces in the Quarterly. Then she would package and mail each issue to I.S.C.A. members and subscribers.

The first issue of the Quarterly contained the work of all 48 copier artist members and was released as a file of loose papers in a flat folder. By the third issue, the Quarterly had grown to over 120 members and had found its form as a plastic comb bound volume of pages, a format it would (mostly) maintain until the final issue in June of 2004.

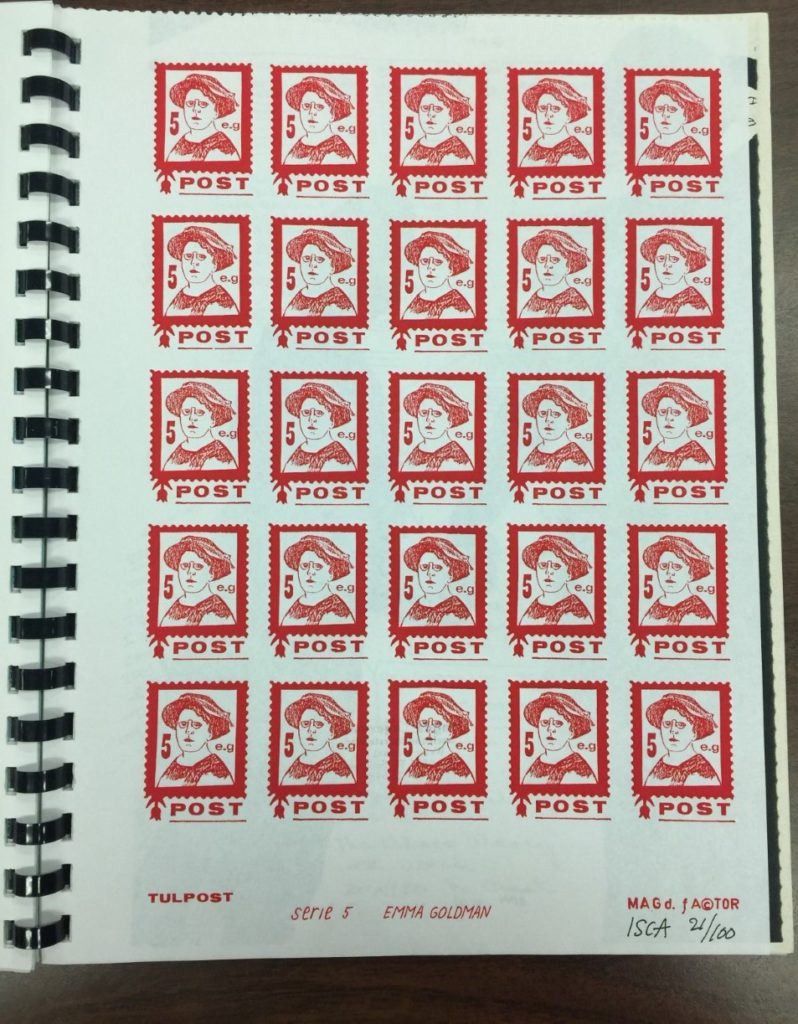

Copier artists creatively stretch the expectations of photocopies by using different colors, sizes, and textures of paper. In issues of the I.S.C.A. Quarterly there are works that have pasted on collages, unique paper cut-outs, applied paint, ink, and sewed on appliques. So long as an artist was using a photocopier as a component of their work, their pieces were fair game for submission to the Quarterly. While some issues were a hodgepodge of works with vastly different subject matter, Neaderland frequently issued calls for work based on a theme, resulting in I.S.C.A. Quarterly issues on “Statues of Liberty”, “Walls”, “The Artist’s Studio”, and “Charles Dickens”, just as a few examples.

In the summer of 1986, Neaderland published the first of what would become an annual issue of the I.S.C.A. Quarterly: the Bookworks edition. The Bookworks issues featured xerographic artists books and book objects and were packaged in cardboard box mailers. Printed on the back of the catalogue for the first Bookworks edition are the opening lines of Ulises Carrion’s essay “What A Book Is”:

A book is a sequence of spaces. Each of these spaces is perceived at a different moment—a book is also a sequence of moments. A book is not a case of words, nor a bag of words, nor a bearer of words. A writer, contrary to popular opinion, does not write books. A writer writes texts.

This series of statements makes clear that the Bookworks editions of the I.S.C.A. Quarterly were meant to challenge our notions of what makes a book.

Because they corresponded and submitted art through the mail, the I.S.C.A. was undoubtedly embedded in the “Eternal Network”. Dating back to the 1950s and still active today, the Network is an informal, global network of artists who communicate by exchanging their mail art via the postal system. Postage stamps, envelopes, and other postal themes frequently appeared in the work of I.S.C.A. members.

Like the Network, the I.S.C.A. was truly international in scope, in Neaderland’s files of correspondence with other artists, there is mail from Japan, Greece, Panama, Spain, Uruguay, and what was formally Czechoslovakia and West Germany. Neaderlander must have gotten quite a lot of mail; in her Editorial Letter from December 1995, Neaderland urges fellow I.S.C.A. members to send packages to a separate mailing address instead of to her Brooklyn address because she had “a small mailbox here in Brooklyn, and a very angry postman.”

Sitting at the intersection of book works and mail art, the work of the I.S.C.A. attracted the attention of Ruth and Marvin Sackner: a Miami based couple who became leading collectors of concrete poetry, artist books, and book objects. When the Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry arrived at the University of Iowa in 2019, their issues of the I.S.C.A. Bookworks editions, which Neaderland had mailed out to Miami over the course of over two decades, were shelved just five rows away from Neaderland’s own personal copies of the I.S.C.A. Quarterly, which had never left New York City until she gifted her records to Special Collections and Archives in 2003.

The records of the International Society of Copier Artists are in good company here in Iowa City with the thousands of pieces of mail art in the ATCA, Fluxus, and Sackner collections. The I.S.C.A. Quarterlies and Bookworks editions are truly delightful to page though. They serve as records of how copier artists responded to major political, environmental, and social issues of their time. In addition, they are reflections of the rapidly changing technology of the 90s and early aughts. For instance, in 1995 Neaderland wrote in her editorial letter that she would soon be purchasing her first personal computer and was excited to not have to literally cut and paste her letters from typewritten pages. Two years later, she had established an email address for the I.S.C.A. and was working on a web site. At their core, though, the I.S.C.A. Quarterlies are a testament to artist’s abilities to find creativity and inspiration within the drudgery of the ordinary, like copy machines – and the twenty-one-year run of the Quarterly serves as a shining example of the radical power of self-publishing.