Are comic books a good vehicle for social critique? Is Superman’s romance with Lois Lane trying to tell us something about our own relationships? Can comics promote racial inclusion?

As a spinoff of the recent symposium on graphic language, Special Collections and University Archives presents The Comics Continuum, an exhibit from our collections available for perusal, research and teaching to the university community and beyond. The exhibit is open on the 3rd floor of the Main Library through the end of November 2011. While viewing the exhibit, please see the labels for any collection numbers (MsCs) that you may be interested in browsing. Once you are done with the exhibit, we encourage you to move beyond the glass cases, come in Special Collections, and request to look at some of our comics collections in the Reading Room.

For more on our specific collections of comics and graphic narrative art, see

http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/spec-coll/resources/guides/ComicBookCollections.html

Here are some of the items you can see in our exhibit.

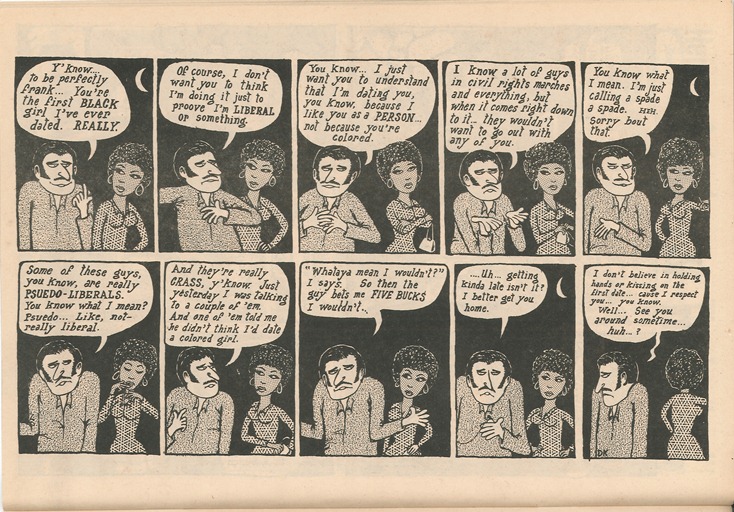

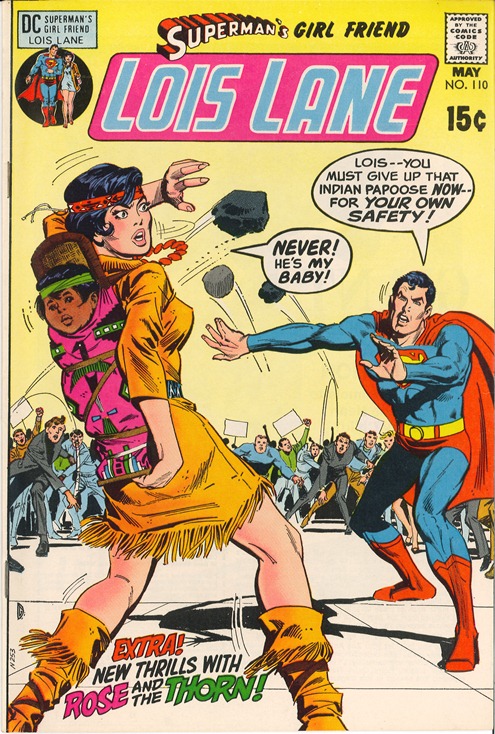

As a genre, comics have the potential to treat political and social issues in ways that promote free and open discussion. The realization of this potential has been shaped by factors such as the contemporary social movements, the vision of the graphic artist, the imperative for business profit, and the expectations of fan communities of entertainment value or social commitment. One of the most important issues of the post-World War Two United States, race relations were treated by comic books with varying degrees of seriousness and sophistication.

Some, like this 1969 issue of the underground Mom’s Homemade Comics, poked fun at liberals for their ambiguous openness to racial inclusion and relationships.

![]()

More mainstream comics such as this May 1971 issue of [Lois Lane] Superman’s Girl Friend used the events of the radical American Indian sovereignty movement to explore issues of motherhood and interracial solidarity.

One of the first African American characters to become a superhero was Dr. William Barrett Foster, who, according to his origin blurb, “pulled himself up out of the Los Angeles slums,” to earn several doctorates and work as director of one of the nation’s most prestigious research labs before becoming a 15-foot tall crime-fighting giant. As in this February 1976 issue of Black Goliath, Dr. Foster’s transformation into a superhero potentially resonated with American anxieties about urban “race riots,” and with the problems of social mobility and the black middle class.

Mom’s Homemade Comics No. 1, 1969 (ATCA Comics, MsC 780) – http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/spec-coll/MSC/ToMsC800/MsC780/ATCA%20Comics.htm

[Lois Lane] Superman’s Girl Friend No. 110, May 1971 (Comic Books of the Bronze Age, MsC 883, Gift of Ken Friedman) – http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/spec-coll/msc/ToMsC900/MsC883/msc883_comicbooks.html

Black Goliath 16 No. 1, February 1976 (Comic Books of the Bronze Age, MsC 883, Gift of Ken Friedman)