Every researcher has likely seen Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) attached to the articles they read, cite, and publish. As unique codes that distinguish a specific research article, dataset, or other digital object, DOIs make it much easier to find and cite the work of other scholars. What you may not know, however, is that DOIs are just one type of persistent identifier (PID). PIDs make your research findable now and in the future, reusable for the long term, and offer new insights into your research.

PIDs, sometimes referred to as persistent digital identifiers (PDIs) or globally unique identifiers (GUIDs) take many different forms. You may have seen an Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) attached to someone’s email signature, or a Research Resource ID (RRID) in a journal article identifying a specific antibody used in the study, or even an International Standard Book Number (ISBN) in a book you’ve read. All of these are PIDs, but don’t let the alphabet soup of initials intimidate you. In essence, all persistent identifiers have two traits that make them powerful.

The first is the part you see and use: the string of letters and/or numbers that uniquely define an entity (like an article, researcher, dataset, or institution). These codes will not change, will not be reused, and are a major reason finding information is so easy with PIDs. The second part of a PID is behind the scenes: the service that locates the resource (or “resolves” it) if its URL changes, ensuring that people who use the PID can always access what they’re looking for. This means, for instance, that even if the URL for an article changes the DOI never will.

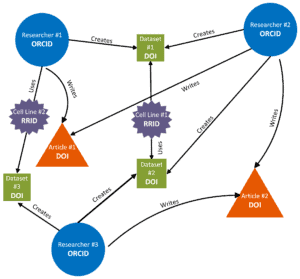

Here’s an example: When a researcher deposits their dataset in the University of Iowa’s institutional repository, Iowa Research Online (IRO), a DOI for the dataset is reserved. A data librarian at UI Libraries will then review and curate the data. When the creator of the dataset gives the green light, IRO will register the dataset, its corresponding metadata, and the DOI with an organization called DataCite, activating the DOI and telling DataCite the landing page for the dataset (i.e., the URL that describes the data and provides access to the files). If IRO reorganized its servers in the future and the URL of the landing page changed, IRO would update this “address change” with DataCite. This ensures that the DOI will still point people to the new, correct URL.

The image below demonstrates how the DOI for a dataset resolves to the specific URL in IRO.

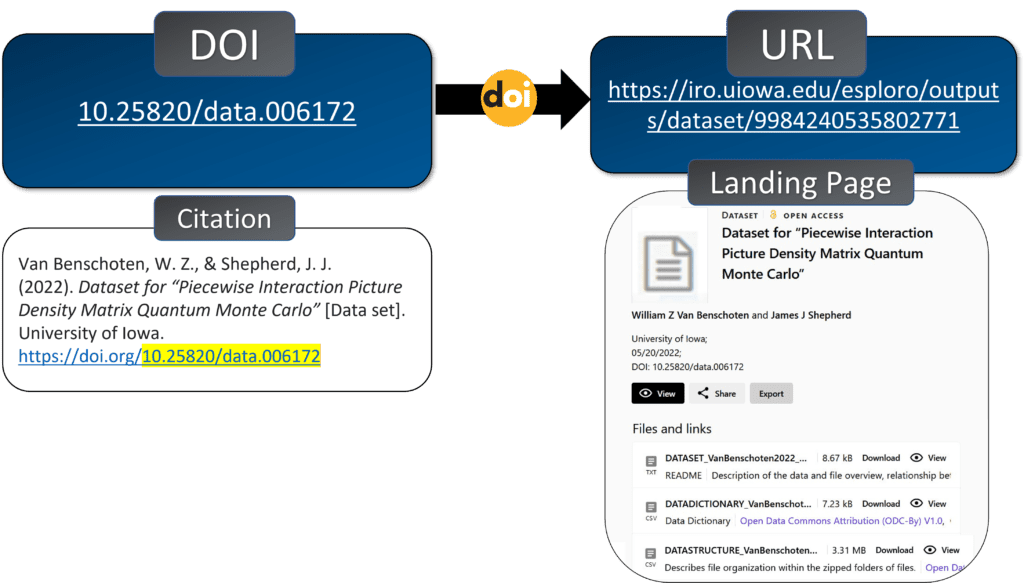

Another important benefit of using persistent identifiers is connection: linking the digital object to everything else that’s associated with it through PIDs, like the people who contributed to the work (through ORCIDs), the places they work (through Research Organization Registry IDs, or RORs), the cell lines they used in the research process (through RRIDs), and articles that use the data (through DOIs).

PIDs thus create a stable network of linked data that makes research outputs more FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), helping people find new connections between data, articles, researchers, institutions, and granting bodies. A researcher who finds your dataset might then be curious if you’re the same person who wrote an article on a similar topic they read in a journal. This might lead them to click your ORCID to discover other research you’ve done, pointing them to the DOI of another dataset you’ve published, which they discover they could use for their own project. This discovery was facilitated by PIDs.

The image below offers an example of how PIDs connect these different entities.

You can do a few things to make the most of PIDs and leverage these connections:

- Most importantly, deposit your data and code into repositories that support PIDs. This enables these vital connections between your dataset and the people, articles, institutions, and granting bodies associated with it. These valuable links are the reason the National Institutes of Health strongly encourage using PID-friendly repositories in their guidelines for Data Management and Sharing Plans.

- Register for an ORCID if you don’t already have one, and use it in your repository deposits, code documentation, CV, personal website, grant applications, and anywhere else you can. It connects others to your research and keeps people from confusing you with another researcher with a similar name. The ORCID system will harvest and connect your research outputs – meaning you don’t have to.

- Use RRIDs in your articles if the journal you’re submitting to supports them. The RRID website includes a list of journals that specifically ask for RRIDs (including Cell, Nature, and PLOS One) as well as a list of journals that will include them in articles if the authors add them.

Each of these steps is small and may not seem impactful on its own, but when all researchers do a few small things to enable FAIR data through PIDs, the entire research ecosystem benefits. If you’d like to learn more about repositories like IRO that support PIDs, reach out to Research Data Services in the Scholarly Impact Department of UI Libraries by email or through our website.