Damien Ihrig, MA, MLIS

Curator, John Martin Rare Book Room

Over time, books can start to show their age. All kinds of things take their toll on a book – fire, pollution, pests, and acidic inks, to name a few. Mostly, though – and this makes me very happy – books just get used. And that use adds up.

Thankfully, we have a crack team of folks who specialize in making sure our books are preserved for as long as possible and continue to be available for our users. Our book this month represents one of the many items that make their way through the gentle and skilled hands of our Conservation and Collections Care staff.

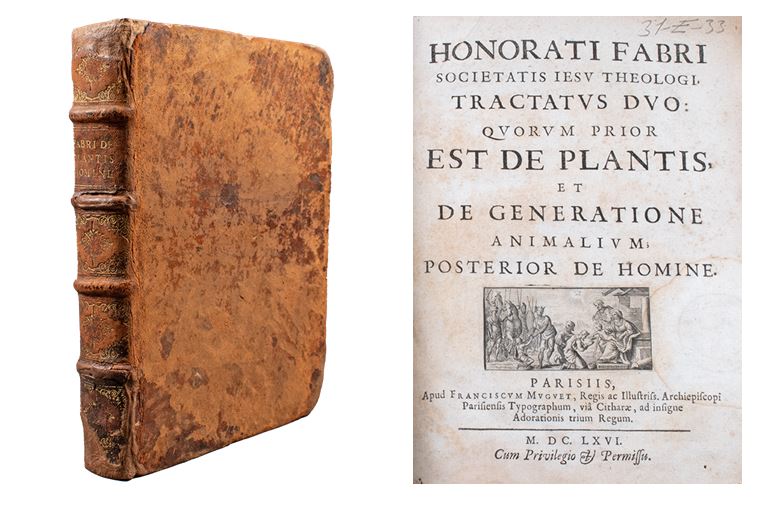

The French scientist and Jesuit priest Honoré Fabri (1608-1688) wrote his Tractatus duo: quorum prior est de plantis, et de generatione animalium; posterior de homine [Two treatises: the first of which is about plants and about the generation of animals; the latter of man] in 1666. It recently spent some time in Conservation for care.

As for Fabri, he was a prominent scientific figure during the 17th century. Jesuit priest was his day job, but he showed an early aptitude and genuine passion for math and science. That passion would eventually get him in trouble with both the Catholic Church and the scientific community, including a short stint in prison and an argument with the famous Dutch polymath Christiaan Huygens that clocked in at five years!

FABRI, HONORÉ (1608-1688). Tractatus duo: quorum prior est de plantis, et de generatione animalium; posterior de homine [Two treatises: the first of which is about plants and about the generation of animals; the latter of man]. Printed in Paris by François Muguet, 1666. 25 cm tall.

Fabri was born April 8, 1608, in Le Grand Abergement. His education started at the Catholic Institute in Belley, where he developed a strong interest in math and science and exhibited a quick wit. He entered the Jesuit Order on October 18, 1626, spending time in Avignon and Lyon for his studies.

Fabri showed a knack for teaching during his tenure as a professor of philosophy in Arles from 1636 to 1638, where he covered subjects like logic, philosophy, and natural philosophy. Fabri’s enthusiasm for teaching and exploring various disciplines led him to hold positions in several Jesuit colleges. He taught logic and mathematics in Aix-en-Provence and later returned to Lyon, where he had a remarkable and productive period as a professor. During this time, he covered a wide range of subjects such as logic, mathematics, natural philosophy, metaphysics, and astronomy. Many of his works were derived from his lectures during this phase.

While Fabri’s teachings were respected, his writings did not sit well within the Jesuit Order for reasons that are not entirely clear. What is clear is that Fabri investigated scientific and philosophical “novelties,” which seem to have irked his conservative colleagues. This led to his removal from teaching in 1646 and a series of reassignments.

He was eventually accused of adhering to the religious and scientific philosophy of Descartes (banned by the church in 1663) and imprisoned.

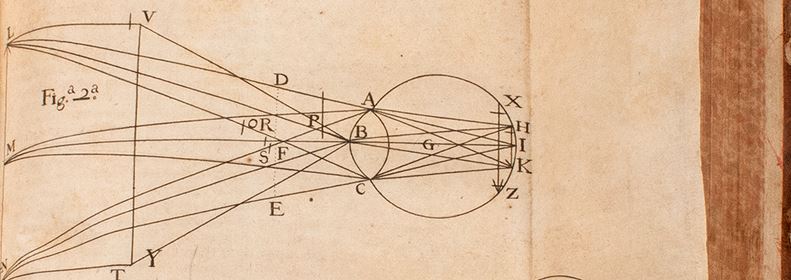

Fabri also engaged in significant scientific debates during his lifetime. His dispute with Christiaan Huygens about Saturn’s rings is especially notable. Initially, Fabri proposed an alternative theory to Huygens’ ring concept, but after a brief five years of debate, he conceded and adopted Huygens’ theory. Fabri also contributed to astronomy by discovering the Andromeda nebula and working on the theory of tides influenced by lunar action.

In the realm of mathematics, Fabri’s work on calculus is noteworthy. He collaborated with Michelangelo Ricci (the “other Michelangelo”) and significantly impacted the development of calculus, particularly influencing Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. In fact, Leibniz placed Fabri with Galileo, Torricelli, Steno, and Borelli for his work on elasticity, vibrations, and the study of motion.

Not content with making his mark solely in mathematics, physics, and astronomy, Fabri made waves in medicine, too, although not without controversy, of course. Some tried to foster a blood feud between Fabri and William Harvey, claiming that Fabri’s lectures indicate he discovered the circulation of blood prior to Harvey. Thankfully, Fabri staunched the flow of discord by stating definitively that “at no time did I ever say that the circulation of the blood had been first discovered by me.”

Contact curator Damien Ihrig to take a look at this book: damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154.