BLEULAND, JAN (1756-1838) Otium academicum : continens descriptionem speciminum nonnullarum partium corporis humani et animalium subtilioris anatomiae ope in physiologicum usum praeparatarum, aliarumque, quibus morborum organicorum natura illustratur. [Academic leisure: containing a description of several specimens of the human body and of exact animal anatomy prepared for use in physiology, and containing a description of other items with which the nature of organic diseases is illustrated]. Printed in Utrecht by Johannes Altheer in 1828. 168 pages. 37 color illustrations and 35 black and white illustrations. 29 cm tall.

BLEULAND, JAN (1756-1838) Otium academicum : continens descriptionem speciminum nonnullarum partium corporis humani et animalium subtilioris anatomiae ope in physiologicum usum praeparatarum, aliarumque, quibus morborum organicorum natura illustratur. [Academic leisure: containing a description of several specimens of the human body and of exact animal anatomy prepared for use in physiology, and containing a description of other items with which the nature of organic diseases is illustrated]. Printed in Utrecht by Johannes Altheer in 1828. 168 pages. 37 color illustrations and 35 black and white illustrations. 29 cm tall.

Otium academicum is Bleuland’s catalog for his extensive anatomical collection that was purchased for the University of Utrecht in 1826. It includes descriptions for over 2,000 specimens and 72 beautifully printed illustrations. Domenico Bertolini Meli’s 2017 book, Visualizing Disease is an exceptional book with a thorough investigation into Bleuland’s process, both pathologically and illustratively. Bertolini also provides a good description of the differences between intaglio printing (e.g., engraving or etching lines onto a metal plate) and lithography (ink on a stone surface).

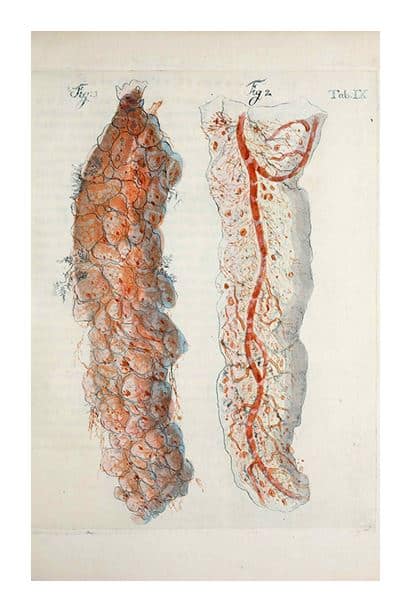

“Otium academicum consists of three parts dealing with anatomy and physiology, comparative anatomy, and pathological anatomy, respectively; they appeared in twelve installments between 1826 and 1828. The illustrations of the first two parts include thirty-six copper engravings printed in color and finished by hand; those of the third part consists of thirty-five black-and-white lithographs and one color engraving; the exceptional pathological plate in color will be discussed below.

The separation between physiological and pathological sections, with his distinction between color engravings versus black-and-white lithographs, is quite striking; all his plates, though, relied on preparations…While striking for the preparation and printing techniques, the overall impression of Bleuland’s colored plates is affected by the artificial look of the images: although Bleuland often rejoiced at the beauty of his colored injections, his colors look like implausible renderings of what an anatomist may find in the morgue, though they were possibly true to his preparations.

The separation between physiological and pathological sections, with his distinction between color engravings versus black-and-white lithographs, is quite striking; all his plates, though, relied on preparations…While striking for the preparation and printing techniques, the overall impression of Bleuland’s colored plates is affected by the artificial look of the images: although Bleuland often rejoiced at the beauty of his colored injections, his colors look like implausible renderings of what an anatomist may find in the morgue, though they were possibly true to his preparations.

The scope of his physiological and comparative sections, as in previous publications, was to highlight the physiological significance of his structural findings; in this respect, by highlighting the fine vascular structure, or what he called the anatomia subtiliore, in the tunics and membranes of his preparations, his presentation was perfectly suitable…

Lithography was the preferred medium for pathology presumably for reasons of cost, because most preparations were not colored through injections, and because the versatility of lithography enabled the artist effectively to capture the key features, such as changes in structure and especially texture. A notable feature of Bleuland’s work is that he often tells us how his preparations were made, which vessels he injected, which colors he used, how slowly he injected them, and at times which substance he used, such as mercury.”(p. 90)

“…lithography: by drawing with an oily crayon on the [stone] slab, wetting it, and then applying a sponge dipped in ink, only the portions drawn by the crayon turned black, because the ink was repelled by the water but had an affinity to oily substances. In this way the stone could be used for printing by repeating the same process as many times as one wished.

Whereas in a woodcut the inked image was in relief and in an intaglio print it was recessed, in lithography it was on the surface or at the same level as the plate, hence the technical term of”planographic prints”; unlike intaglio prints, lithographs left virtually no mark of the stone on the paper….eventually lithography allowed for considerable subtleness in tone and effectiveness in representing textures. In addition, the process was simpler, cheaper, and more direct than producing intaglio prints, corrections were easier, and more copies could be printed without wear…” (p. 21) Bertoli, Visualizing Disease, 2017.

The book is in great condition. The paper has very little staining and the images are stunning. It is bound with a leather spine covering and marbled paper. It is an excellent example of a medical scientist maximizing the printing technology of the day to present their work and visual arguments as effectively, and beautifully, as possible.

If you are interested in seeing these or any other rare materials, please contact Damien Ihrig at damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154 to arrange a visit in person or over Zoom.