Every year, the Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA) awards the Linda and Richard Kerber Travel Grant to a researcher whose work would benefit from using collections in the Archive and who resides outside a 100-mile radius of Iowa City, Iowa, with preference given to graduate students. The grant’s 2024 recipient was Lillian Nagengast.

Lillian Nagengast experienced a Midwestern upbringing in Bloomfield, Nebraska, a town with a population that over around just 1,000. For college she headed east and attained a BA from Boston College and then an MA in English from Georgetown University. Nagengast is now pursuing a PhD in American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, and her scholarship has led her back to her roots. Her dissertation prospectus will focus on the Midwest, particularly woman and LGBTQ individuals who forged community, belonging, and progressive coalitions in the region from the 1960s to the present day.

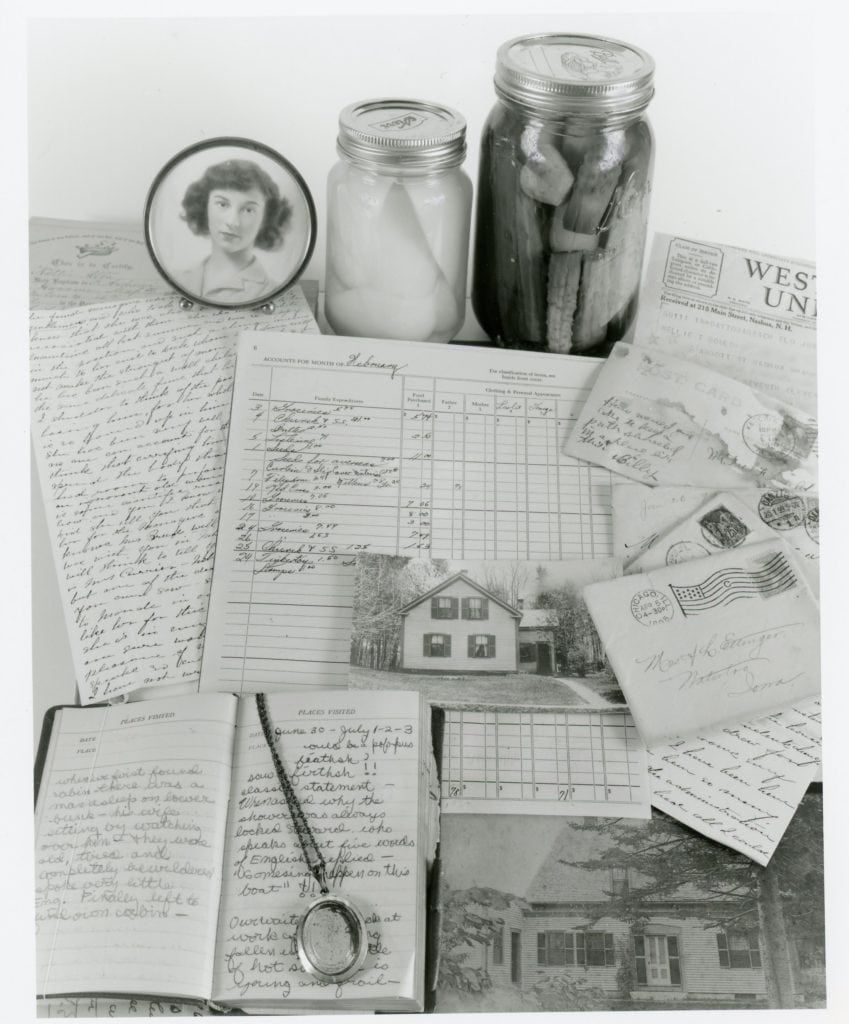

While researching the rural Midwest, Nagengast encountered works including On Behalf of the Family Farm: Iowa Farm Women’s Activism since 1945 by Jenny Barker Devine and When a Dream Dies: Agriculture, Iowa and the Farm Crisis of the 1980s by Pamela Riney-Kehrberg. Both built their arguments using the voices of rural women as recorded in diaries, letters, and oral histories. Nagengast found herself wondering where these academics gathered this wealth of primary sources. The search led her to the IWA, which both historians had visited, and its rich collections documenting everyday rural life in 20th century Iowa. Thanks to the Linda and Richard Kerber Travel Grant, Nagengast was able to visit the IWA and see some of these sources for herself.

While perusing the Archives, Nagengast searched for evidence of grassroots organizing by women and queer people in rural Iowa by consulting collections including the Voices from the Land Oral History Project, the Mujeres Latinas Oral History Project, and the Anita Crawford papers, among others. These collections, she believes, speak to each other in surprising ways across time periods, locations and ethnic backgrounds.

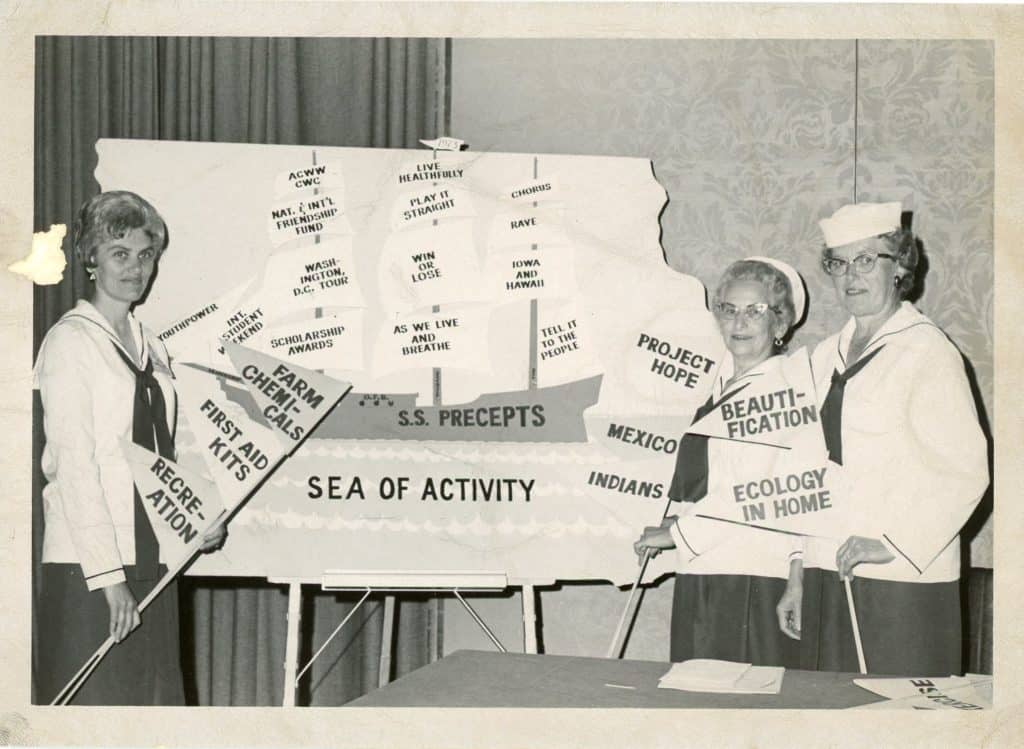

For instance, while the second wave feminist movement was blooming in more urban areas, the women in these oral histories worked outside of mainstream feminist organizations. Women like Anita Crawford, a farmer and volunteer for the Buchanan County Farm Bureau, engaged with the Iowa Women’s Political Caucus over the issue of inheritance taxes, which affected women farmers, rather than over the social issues more commonly associated with the feminist movement of her time. One woman who stuck out to Nagengast was Barbara Grabner, who worked with PrairieFire Rural Action, a non-profit focused on grass-roots efforts to address the 1980s Farm Crisis, in which many Iowans lost their family farms. Grabner was a leader in advocating for women on family farms, but noted in her oral history that “You don’t use the word feminist around a lot of these people, which they really were, but you wouldn’t call them that.” Nagengast hopes that these archival insights into how women did objectively feminist work outside of the feminist label will make up the bulk of her first chapter.

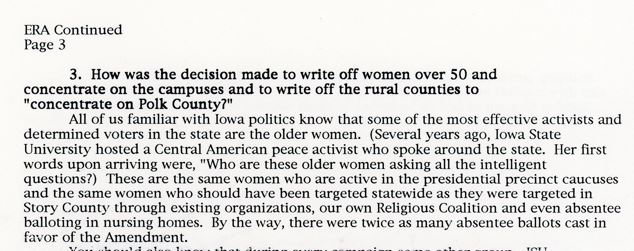

Again and again Nagengast found evidence of fractures in feminist coalition building, particularly among national (often urban) and local (particularly rural) organizations. This was typified by her favorite document in the Archives, a four-page letter from the Story County Equal Rights Amendment Coalition, a local organization, to the national Fund for the Feminist Majority, written in the aftermath of the ERA’s 1992 defeat in Iowa. The letter enumerated the ways in which the Coalition believed the Fund’s tactics contributed to the loss, claiming the Fund’s representatives refused to collaborate with locals, made rude comments about them, and decided to “write off women over 50 and concentrate on the campuses and to write off the rural counties to ‘concentrate on Polk County.'” The letter is detailed and unsparing, and was copied to feminist luminaries at Ms Magazine and Iowa NOW. Nagengast thought she had struck gold. “I’d like it framed in my office,” she joked.

Now that she’s back home, Nagengast plans to write her prospectus and then begin writing her dissertation itself. She has high hopes for the project, including drafting a conference paper, writing a book, and hopefully coming back to IWA for future research.