This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the seventh installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of Iowa Women’s Archives and other local repositories. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020.

The State Historical Society of Iowa holds rich collections on the history of Black women in Iowa, notably the records of the Iowa Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. A small fraction of those materials were digitized in 2010 to include in the Women’s Suffrage in Iowa Digital Collection. This blog post highlights that digitized material, but we hope that once the pandemic has subsided, you will be inspired to visit the State Historical Society to see what else makes up this remarkable collection. The physical records contain material related to over sixty years of club business, including two scrapbooks filled with meeting programs, photographs, newspaper clippings, and correspondence. You can read more about these records here.

2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, granting women the right to vote. It also marks the 150th anniversary of the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment (1870), which granted universal suffrage to African American men, but not women, following emancipation and the Civil War. In the years between 1870 and 1920, women across the nation continued to fight for the right to vote and worked to actively demonstrate their fitness for the full rights of citizenship. This post considers the ways that African American women in Iowa contributed to that struggle through their participation and activism in the Iowa State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, founded in 1902. When this group became affiliated with the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACW) in 1910, African American women in Iowa joined a nationwide network of over 10,000 Black clubwomen, committed to “Lifting as we climb” and demonstrating to “an ignorant and suspicious world that our aims and interests are identical with those of all good aspiring women.”

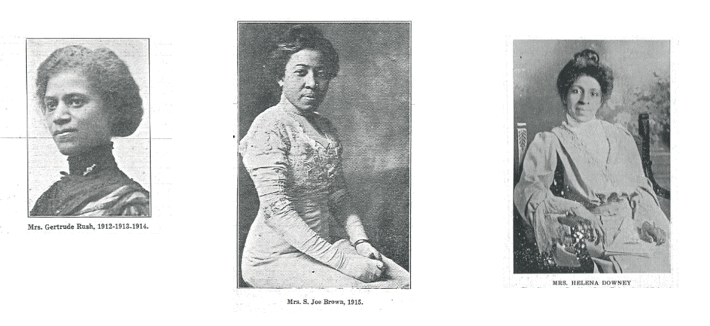

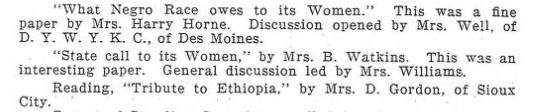

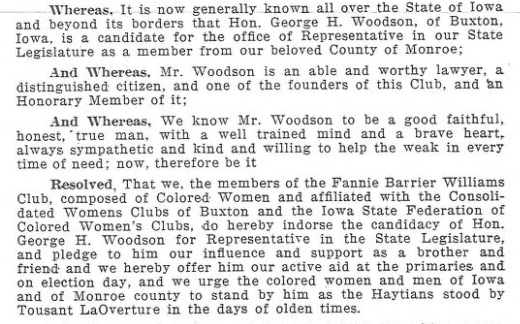

The Women’s Suffrage in Iowa Digital Collection includes digital copies of the Proceedings from several annual meetings of the Iowa State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. Annual meetings were held in cities across the state and brought together officers, delegates, and club members to hear reports on club business, listen to speeches and papers, and pass resolutions that signaled their commitment to particular projects. The meeting records included in the Iowa Digital Library represent just a handful of the Proceedings that are part of the Iowa Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs records at the State Historical Society. Dr. Denise Pate Spruill, who earned her Ph.D. in History from University of Iowa in 2018, conducted extensive research in these records for her dissertation, “‘From the Tub to the Club:’ Black Women and Activism in the Midwest, 1890-1920.” Spruill argues that, “In the upper Midwest, clubs and early community activism served as a conduit for black women, providing a venue for them to hone their organizational skills, create networks, recruit members and develop programs to aid in racial uplift, increasing their authority and power as women in their communities.” There is much to explore in the digitized Proceedings, but this post highlights just three examples of how African American women in Iowa used the club movement to perform and display their fitness for citizenship.

First, women used the annual meetings to practice and demonstrate their speaking skills and their ability to grapple with important issues. In her study of Black clubwomen in Iowa, Spruill notes that delivering speeches, reading papers, and leading discussions at such meetings “prepared these women to be more engaged in social, economic and political discussions” more broadly. Members wrote and spoke about a wide range of topics, including education, social ethics, and the importance of Black men and women’s service and support during the Great War (as World War I was known at the time). Women also discussed the vote directly with arguments about “Why Women Should Vote” and “What [the] Negro Race owes to Its Women.”

Second, women in the Iowa State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs engaged political candidates and elected officials directly, despite their own exclusion from the polls. In 1912, at the 11th annual meeting, held in Sioux City, club members voted to endorse George H. Woodson’s candidacy for state representative from Monroe County. Woodson was a prominent African American lawyer, a leader of the Black Republican Party in Iowa, and the first African American in the state’s history to be nominated to the state legislature. As part of their endorsement, members pledged “to him our influence and support as a brother and friend and we hereby offer him our active aid at the primaries and on election day, and we urge the colored women and men of Iowa and of Monroe county to stand by him as the Haytians stood by Tousant LaOverture [sic] in the days of olden times.” They noted further, “we believe Mr. Woodson will represent the county, in the very best way, and fight for Women’s rights.” This endorsement and the call for Black women’s active political engagement demonstrated that despite their exclusion from casting their own ballots, clubwomen were invested in the political landscape, had the power to influence public opinion, and wanted to support candidates who had the interests of women and African Americans at heart. In this and other instances, the group pointed to the history of Black participation in fights for independence (as in the Haitian and American revolutions) as a demonstration of their capacity and their fitness for citizenship.

Finally, African American clubwomen used their voices and political influence to demand that white public officials take a stand against lynching and racial violence. Following a visit from journalist and activist Ida B. Wells in 1894, Black women in Des Moines formed an anti-lynching organization. Over time, the Iowa State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs passed public resolutions condemning lynching and mob violence, worked “to arouse public sentiment” on the issue, and advocated for anti-lynching legislation. At the 14th annual meeting in Cedar Rapids in 1915, the group praised local officials who they had pressured to take action in “eliminating the pictures which are objectionable to the Afro-Americans of the state.” They were referring to the “souvenir” postcards of lynchings that were common in the early twentieth century. These brutal scenes of racial violence and white spectatorship had apparently been disseminated in Iowa, including in Cedar Rapids and Des Moines. Denise Pate Spruill argues that, for Black clubwomen in Iowa, 1915-1920 was a critical period during which “Long-time anti-lynching activism evolved from passing organizational resolutions to taking a successful public stance against the dissemination of murderous images that resulted in a direct response from an elected official.”

These examples illustrate some of the ways that Black clubwomen built political skills and exercised political influence long before they gained access to the full privileges of citizenship. Do you want to know more about how these and other Iowa women campaigned for the ballot directly? Take a look at the rest of the annual meeting records – and other primary sources – in the Women’s Suffrage in Iowa Digital Collection. Thank you to the State Historical Society of Iowa for helping us share these remarkable records and to Dr. Denise Pate Spruill for providing a rich historical context for the Proceedings. All images in this post are from the Iowa Association of Colored Women’s Clubs records, 1903-1972, Special Collections, State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines.