What follows is one final blog post from our former Olson Graduate Assistant, Jillian Sparks, who attended the SHARP conference July 7-10, 2015 to present a poster related to her cataloging work here in Special Collections.

The Society for the History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing (SHARP) is an international organization dedicated to book history and print culture. SHARP describes their research focus as, “the composition, mediation, reception, survival, and transformation of written communication in material forms from marks on stone to new media. Perspectives range from the individual reader to the transnational communication network” (sharpweb.org). There are over a 1,000 members from more than 40 countries who provide a truly global perspective of book history. Due to its large international community, the conference location rotates between the Western and Eastern hemispheres each year—typically North America and Europe.

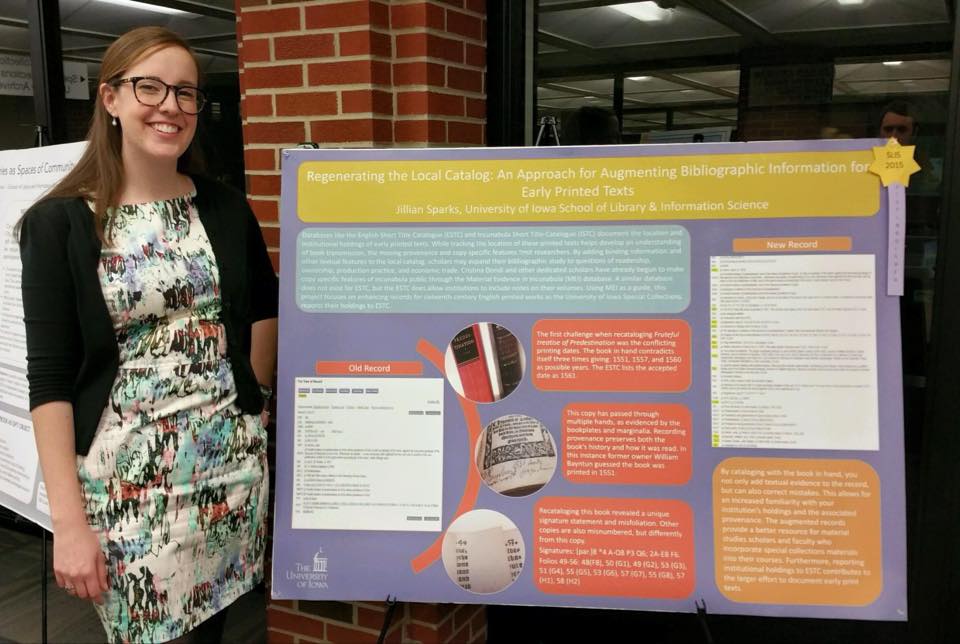

I first learned about SHARP while attending the Digital Humanities Summer Institute in 2012. Adrian van der Weel, the keynote speaker and my course instructor, highly encouraged joining SHARP if we were interested in book history. I joined the same afternoon and after three summers, I was finally able to attend the annual conference this summer in Longueil/Montreal as a master’s student poster presenter. I presented my final poster from the University of Iowa’s School of Library and Information Science program titled “Regenerating the Local Catalog: An Approach for Augmenting Bibliographic Information for Early Printed Texts.” The theme this year was “The Generation and Regeneration of Books” and was hosted by the Groupe de recherches et d’études sur le livre au Québec, the University of Sherbrooke, McGill University and the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. The conference was truly a bilingual event with presentations in both French and English. Over 350 people traveled to Québec to participate.

Scholars from all disciplines and librarians alike attend SHARP, and the conference program reflects this diversity. I attended sessions on special collections instruction, cataloging, and pivotal collectors. “Old Books and New Tricks: Regenerating the Library Visit” has been the most helpful session on special collections instruction out of all the conferences I have attended. Gale Burrow from Claremont College presented on how to turn a one-time visit into a two part lab series that focuses on primary research in the first lab and the secondary sources in the second lab. Karla Nielsen demonstrated how Book Traces, a crowd-sourced web project aimed at identifying unique copies of 19th- and early 20th-century books on circulating library shelves, was successfully carried out at Columbia University. CLIR postdoctoral fellow at Southwestern University, Charlotte Nunes, discussed the emotional connection her students experienced while transcribing Latino oral histories and the importance of capturing the students’ oral histories on their project work. The last presenter, Amanda Watson from Yale, showed how she has collaborated with special collections to integrate technology into the class visit. All four presenters illustrated creative methods of teaching that I look forward to incorporating into my professional career.

Because of my interest in copy specific cataloging and in relation to my own work on cataloging 16th-century books at the University of Iowa, the panels on “Pivotal Collectors” and “Early modern Women and the Book (II): case Studies in Ownership, Circulation, and Collecting” served as interesting comparisons. In the first panel, presenters discussed the familiar issues of how to catalog and organize famous personages’ personal collections. In the second panel, speakers addressed the problem of how to find someone’s books after the collection has been separated and sold. In her presentation “Finding Frances Wolfreston in Online Public Access Catalogues: How Electronic Records Can Lead Us to Early Modern Women Readers,” Sarah Lindenbaum demonstrated how Frances Wolfreston’s unique signature as noted in various catalog records enabled her to trace the dispersion of her books. The discussion surrounded the general value of provenance notes and included mention of Provenance Online Project also known as POP.

Other presentations on embroidered bindings (Amanda Pullan) and the history of dog-earing books (Ian Gadd) were equally exciting and all of the SHARP panels appealed to my love of book history. The most fulfilling aspect of the conference was SHARP’s dedication to encouraging emerging scholars. There was a specific dinner for master’s and PhD candidate presenters. The poster session and PhD candidate papers did not conflict with other sessions, thus allowing all conference attendees to engage with their research. I personally benefited from the feedback and encouragement I received during the poster session. Most importantly, I left SHARP feeling welcome and excited to be a member of the organization and enthused about book history as a discipline.

Relevant links:

Sparks, Jillian A. Regenerating the Local Catalog: An Approach for Augmenting Bibliographic Information for Early Printed Texts http://ir.uiowa.edu/slis_student_pubs/1

Accompanying digital exhibit: http://sparks.omeka.net

SHARP’s website: http://www.sharpweb.org

SHARP 2015 conference site: http://sharp2015.ca/en/home/

Book Traces: http://www.booktraces.org/

Provenance Online Project (POP): https://provenanceonlineproject.wordpress.com/