If you have been following any of our social media feeds over the past few days, you may have noticed photos popping up of newly-acquired incunables. So, what’s going on here? First, some background:

Incunables are books printed in Europe during the fifteenth century, between 1450 and 1501, examples of the earliest printed books. The incunabula period is the focus of a great deal of study—the development of printing, and how it affected the design, distribution, and reception of books, remains central to our understanding of book history.

Incunables are books printed in Europe during the fifteenth century, between 1450 and 1501, examples of the earliest printed books. The incunabula period is the focus of a great deal of study—the development of printing, and how it affected the design, distribution, and reception of books, remains central to our understanding of book history.

Here at Iowa, we have long held a respectable collection of incunabula, and these books are frequently called for in classes and exhibitions. In recent years, these books have been examined extensively by Tim Barrett for his study of early papermaking, and Iowa is also home to the Atlas of Early Printing, an interactive overview of the spread and development of printing in Europe. The UI Center for the Book continues to pass along the art and craft of letterpress printmaking that first flourished in the incunabula period.

Our recent acquisitions are an attempt to add examples of books and subjects in the incunabula period that we have not had previously. This collection development has been made possible due to the support of the University Libraries acquisitions fund and the Libraries’ Collection Management Committee.

Special Collections Librarian Pat Olson took charge of this opportunity and identified an outstanding mix of possibilities that enhance our collection in many ways. Among these dozen new titles is the first illustrated edition of Dante printed in Venice. Until now, our incunables largely represented just a single language: Latin. The occasional ancient Greek was the only exception. Our new Dante, however, is in Italian, and so it’s one of our first incunables printed in a vernacular language. The other, also just acquired, is Monte dell’orazione, a private devotional text intended specifically for women. The copy we just acquired is particularly notable for retaining the very rare illustrated wrapper—or to risk oversimplification, the original illustrated paperback binding.

Special Collections Librarian Pat Olson took charge of this opportunity and identified an outstanding mix of possibilities that enhance our collection in many ways. Among these dozen new titles is the first illustrated edition of Dante printed in Venice. Until now, our incunables largely represented just a single language: Latin. The occasional ancient Greek was the only exception. Our new Dante, however, is in Italian, and so it’s one of our first incunables printed in a vernacular language. The other, also just acquired, is Monte dell’orazione, a private devotional text intended specifically for women. The copy we just acquired is particularly notable for retaining the very rare illustrated wrapper—or to risk oversimplification, the original illustrated paperback binding.

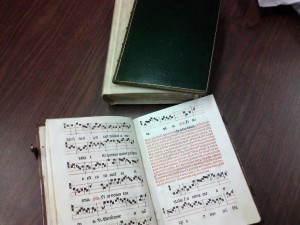

We filled one of our more significant gaps with the acquisition of our first 15th-century Bible, and in an early pigskin binding to boot. Another first for us is our first Spanish incunable, a book of music printed in red and black at Seville in 1494. We purchased our first 15th-century edition of Ovid, too, here in its original leather-covered wooden boards and retaining its original brass furniture. Early science has been another sparsely covered subject for us, so we acquired a lavishly illustrated astrological text. (NB: What passed for science in the 1400s may not pass for science today.) We also acquired a rather crude dialogue intended for children and the less sophisticated—a rare survival, insofar as such texts were less commonly printed and more commonly read to pieces.

the acquisition of our first 15th-century Bible, and in an early pigskin binding to boot. Another first for us is our first Spanish incunable, a book of music printed in red and black at Seville in 1494. We purchased our first 15th-century edition of Ovid, too, here in its original leather-covered wooden boards and retaining its original brass furniture. Early science has been another sparsely covered subject for us, so we acquired a lavishly illustrated astrological text. (NB: What passed for science in the 1400s may not pass for science today.) We also acquired a rather crude dialogue intended for children and the less sophisticated—a rare survival, insofar as such texts were less commonly printed and more commonly read to pieces.

In all cases, we sought books in early (if not original) bindings. Given the serious interest in early papermaking here at Iowa, we made it a point to pursue books with untrimmed leaves, which serve as uncommon witnesses to original paper sizes. We searched for books with valuable marginalia, interesting provenance, and varying degrees of decoration by hand. Most of these books do have early marginalia, an invaluable resource to support the growing scholarship on the history of reading. Perhaps the most remarkable in terms of provenance is a sammelband (multiple books bound together) printed by the famous scholar-printer Johann Amerbach. Our copy is not just a well preserved example of a 15th-century sammelband, but it contains an inscription noting its donation to a local monastery by the printer himself. As far as textual decoration is concerned, these new acquisitions run the gamut from crude DIY initials to professionally executed penwork and illumination.

papermaking here at Iowa, we made it a point to pursue books with untrimmed leaves, which serve as uncommon witnesses to original paper sizes. We searched for books with valuable marginalia, interesting provenance, and varying degrees of decoration by hand. Most of these books do have early marginalia, an invaluable resource to support the growing scholarship on the history of reading. Perhaps the most remarkable in terms of provenance is a sammelband (multiple books bound together) printed by the famous scholar-printer Johann Amerbach. Our copy is not just a well preserved example of a 15th-century sammelband, but it contains an inscription noting its donation to a local monastery by the printer himself. As far as textual decoration is concerned, these new acquisitions run the gamut from crude DIY initials to professionally executed penwork and illumination.

There really is something for everyone, and we can’t wait to share them. Once they have been catalogued and properly housed, these books may be viewed by request in our reading room during regular hours. And keep an eye out for an announcement coming at a later date of an opportunity to view these new acquisitions in person, while learning about how incunables are being studied today.

Any chance they will be digitized and shared with the public (asks this member of the public)?

I would say that’s a good possibility–and even better would be digitizing all of our incunables. We have already completed all of our medieval manuscripts (http://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/mmc/), so a step forward in time seems sensible!