How did a man from Iowa help launch the Soviet steel industry? What was it like for American engineers to work side by side with Russian workers in the 1930s? Who did Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev greet as an old friend when he visited Iowa in 1959? Read on to find out the answers.

In 1931, Henry Zimmerman of Lone Tree, Iowa traveled to Kuznetsk, Siberia, to oversee the building of steel mills in the Soviet Union. The University of Iowa Special Collections has been collaborating with Russian History doctoral student Irina Rezhapova (Kuzbass Institute of the Federal Penal Service) on a special digital project which tells the story of Zimmerman’s journey. Special Collection will be making available online Henry Zimmerman’s personal letters and scrapbooks of photographs, news clippings and ephemera about his time in Soviet Siberia – all part of our Records of the Zimmerman Steel Company (http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/spec-coll/MSC/ToMsC900/MsC850/zimmermansteelworks.html).

This is Entry 3 of 3 of the Zimmerman Steel Journey.

What did the Americans and Russians do for fun?

It seems that the Western advisers were quite active in their leisure time. “Foreigners were fond of sports, music and dances. Walks in the country were practiced in summer. ‘Their favorite place was the River Tom and parks,’ recalled Raisa Khazanova. Excursions on Kuznetskstroj were arranged for foreigners and they were also carried to the nearest industrial cities, such as Prokopevsk.” (O.A. Belousova, “Foreign Experts and the Soviet Reality: Life of the First Kuznetsk Builders.” 2003, translation by Irina Rezhapova)

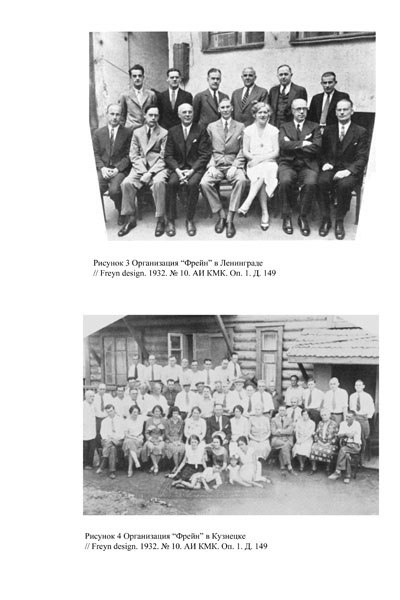

Pictures suggest that like Henry Zimmerman, some of the Western steel specialists took their families with them to Siberia. Some were likely single men. While there is no direct evidence of intimate relationships between Western engineers and Soviet workers, they were likely collegial, and may have even become friends.

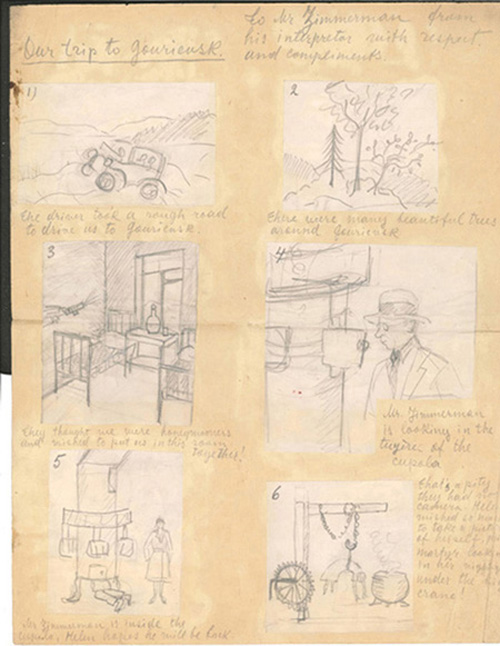

As his Russian translator’s sketch suggests, Henry Zimmerman and his companion “Helen” took a trip to Gourievsk, presumably for him to visit another steel mill in the making. But this trip was not all work and no play. Look closely to see some of the things Zimmerman and his fellow travelers found funny and relaxing.

The Watchful Eye of Big Brother?

Clearly, for the Soviet Communist leadership, some of the relationships between the Western specialists and their Russian counterparts were too close for comfort.

“On August 16, 1931 a special “Foreign Bureau” was established. Similar bureaus worked in all large industrial centers of the USSR, including Kuznetskstroi. The Foreign Bureau wasn’t just a mediator between foreign and Soviet experts. The bureau also played the role of adaptation point. The foreign experts who arrived on building within first three-four days came to foreign bureau where they were given some explanatory talk: “where they arrived, why they were there, and how they should feel”; there was also a pep talk about household and political life.

In the beginning of 1931 the Party Committee of Kuznetsk Metallurgical Plant requested that the Foreign Bureau organize for foreigners a political circle in their native language and clubs for studying Russian. Special attention was to be given to the propaganda of the Soviet system, and socialist forms of work (socialist competition).

As such high political goals were put on the Foreign Bureau, it is no wonder that its activities were watched by the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD). Any compromising evidence or spiteful remarks were documented; any errors in work or private life were carefully fixed.

Anfisa Kuzminichna Nikulina was the manager of the Foreign Bureau in Kuznetsk in 1932. She was born in 1901, and had a higher education degree. Since April, 1920 she had been a member of All-Union Communist Party, with no other party affiliations. Nikulina had also served in the Red Army. During her work in the Foreign Bureau at Kuznetsk, she was accused of infringement of interests of Germans in favor of Americans. Later she was expelled from the party for working for personal interests.

Previously an economist in Kuznetsk, Raisa Semenovna Khazanova became the next manager of the Foreign Bureau. According to Evtushenko, a member of the City Committee of Education, “In 1931-32 Raisa Hazanova was expelled from the Communist Party for the relations with foreigners, drinking alcohol with them, giving them prostitutes…” (O.A. Belousova, “Foreign Experts and the Soviet Reality: Life of the First Kuznetsk Builders.” 2003, translation by Irina Rezhapova)

What is the legacy of Zimmerman’s journey?

Overcoming obstacles such as the harsh Siberian weather, isolation, technological challenges, distrust and professional jealousy, Zimmerman and other Western specialists worked with their Russian partners to get the Soviet steel industry off the ground. Zimmerman came to be so highly regarded that a film was made of him working with the Soviet steel foundries (Henry Zimmerman, letter of October 11, 1966). While the emergence of the Cold War with the Soviet Union retarded technological cooperation for decades, the Russians remembered Zimmerman’s work in more than one way. In his letters from the 1960s, Zimmerman recalled that when Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev visited Iowa in 1959, he took time to meet with Henry Zimmerman, telling him that a foundry that he built in the early 1930s was still operating perfectly. His April 17, 1971 obituary in the Davenport-Bettendorf Times-Democrat claims that “There is a monument in Red Square, Moscow, Russia, that pays tribute to Mr. Zimmerman and 50 other American engineers who showed the Russians how to develop the steel industry.”

If you liked Zimmerman’s story, you can read our finding aid here: http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/spec-coll/MSC/ToMsC900/MsC850/zimmermansteelworks.html

Please check our blog for the first two entries on the Zimmerman Steel Journey.

By Gyorgy “George” Toth, PhD Candidate in American Studies, Olson Fellow, The University of Iowa Special Collections & University Archives,

With

Irina Rezhapova, PhD Candidate, Russian History, Kuzbass Institute of the Federal Penal Service