Earlier this week, the Studio launched Scholarship@Iowa, a curated set of pages promoting scholarly archives related to historically underrepresented groups. To introduce that initiative I wrote a blog post touting the merits of these archives and their ability to help us see ourselves as a part of longstanding tradition of excellence and discovery at the University of Iowa.

In that same spirit, this week we have released over 3,000 manuscript pages into a new and related DIY History collection called Scholarship at Iowa. The collection brings into public view 22 handwritten theses dating primarily from the nineteenth century. More than half of the theses were written by women and the topics are primarily scientific. These documents provide a fascinating window into the nature, scope, and aims of scholarship being carried out at the University by undergraduate and graduate students well over a hundred years ago. They also help tell the story of women within the scholarly enterprise at the UI.

While PDFs of the theses are posted in our institutional repository, Iowa Research Online (IRO), they’re not text searchable. That’s where DIY History comes in. By inviting the public help in the transcription of these materials, we aim to make them searchable. Completed transcriptions will be added to IRO to aid in the discoverability of the documents.

Among these theses you’ll find:

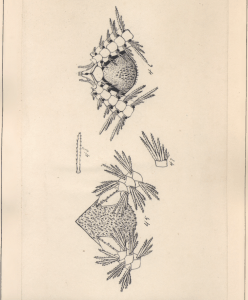

- A brief description of nine species of Hepaticae found in the vicinity of Iowa City, 1886, by Mary F. Linder (B.S. ’86)

- The Histology of the Common Frog, 1887, by Rose B. Ankeny (B.S. ’87, M.A. ’90)

- Vegetable secretions and the means by which they are effected, 1888, by Kate L. Hudson (B.S. ’88)

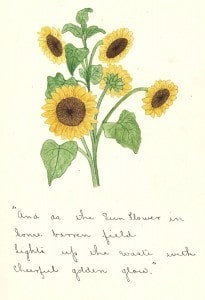

“And as the sunflower in/Some barren field/Lights up the waste with/Cheerful golden glow.” The Sunflower as a Type of Flowering Plants, Anne B. Jewett, 1890. - The Mosses of Iowa City and Vicinity, 1888, by Annette Slotterbec (B.S. ’88)

- The sun flower as a type of flowering plants, 1890, by Anne B. Jewett (B.S. ’90)

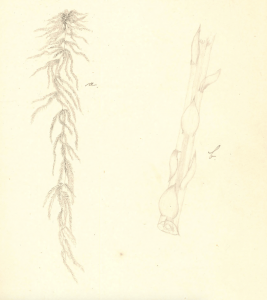

- The Fertilizing Cell, Its Varying Form and Behavior, 1890, by Nelly Peery (B.S. ’90, LL.B. ’93)

- The Slime Moulds of Eastern Iowa, 1891, by Minna P. Humphreys (B.S. ’91)

- Derivatives of hydroxylamine, 1892, by Agnes E. Otto (B.S. ’92)

- Ophiuridae of the West Indies, 1893, by Leah May Gaymon (B. Ph. ’92 and M.A. ’95)

- The terrestrial Adephaga of Iowa, including descriptions of all known species which occur in the state, with notes on their habits, distribution, synonymy, etc., part 1 & part 2, 1895, by Fanny Thompson Wickham (B.S. ’90, M.S. ’95)

- The ethical tendency of the English novel, 1897, by Helen M. Harney (B.Ph. ’90)

- Previous legislative experience of United States senators, 1912, by Agnes Wallace Smith (B.A. ’11)

When I was introduced to this collection by my colleague Wendy Robertson, I was struck by its humanity. The calligraphy and design of the title pages, the detail of the illustrations, the idiosyncrasy of the handwriting. I had not expected the people who wrote these works to be so present in them. I expect that of handwritten letters, but (perhaps tellingly) I didn’t expect it of these (mostly) scientific theses. And looking over them, I was drawn back to my own time as a graduate student toiling away on a dissertation. I was reminded of how many of us come to see our work as both apart from us and as a part of us. I wondered how these writers (and artists!) felt as they toiled here on the thinning edge of the nineteenth century.

It’s not hard to hear the enthusiasm in lines like this one from undergraduate student Annette Slotterbec (B.S. ’88) in “The Mosses of Iowa City and Vicinity”:

In no tribe of plants is there so great a similarity between the different species. A simplicity and uniformity of structures runs through the entire family. The individuality of each species is revealed by the microscope, the stem, the leaves, the fruits, so alike they appear in their structure and their flaws, so unalike in their development.

Elsewhere she notes a “beauty of form and ingenuity of structure as though [the mossses] were the mightiest monarchs of the forest.” The buoyancy there is infectious. Who was this enthusiastic undergraduate writing gleefully about mosses here on the cusp of her Bachelor of Science? What did she want for herself and her scholarship in 1888 looking forward to a coming century?

I found myself captivated by the same curiosity that has made Iowa Digital Engagement and Learning’s Archives Alive project so successful. Last year, my colleague Kelly McElroy (now a Student Engagement and Community Outreach librarian at Oregon State University) and I wrote an article on the merits of connecting students with history in this way. And here I was, like my students, like Annette Slotterbec, placing something under the microscope, investigating its individuality.

History is tantalizing. It is (at the risk of making a bad pun–from a guy who wrote his dissertation on James Joyce and the public house) intoxicating. So, I looked up Annette Slotterbec, and a partial story emerged.

She had clearly been an active presence in the intellectual life of the University, competing in the declamatory contest the year she graduated. As The Vidette Reporter, May 26, 1888, notes on page four:

The ladies preliminary declamatory contest was held in Zet Hall last Wednesday afternoon. Prof. Anderson was the only judge. The contest resulted in the choice of the following persons to speak at the final contest held during commencement week: Anna Balor, Florence Brown, Annette Slotterbec, Myrtle Lloyd, Ella Graves and Miss Musson.

After graduation she earned a certificate in scientific temperance instruction (a fascinating movement in education) en route to her career as a high school teacher of German and Science at “the high school in Elgin, Illinois” in 1891. A decade after she graduated she was mentioned (and arguably slighted) in T.E. Savage’s short paper, “A Preliminary List of the Mosses of Iowa,” in the Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Sciences 1898, volume VI. In which he noted:

Specimens of the more common species of this list have been collected and used in the laboratories of the university during many years. More particularly, Miss Annette Slotterbec, in 1888, collected and identified some forty specimens. But on the whole it has been deemed better to record the collection of such material only as has been gathered for the preparation of this paper.

So there I had been idly looking through the undergraduate thesis of Annette Slotterbec, and there I was tracking down bits and pieces of her intellectual life. This happens all the time with DIY History. It seduces you into asking questions about people and their lives. And as you follow the thread, you find interesting stuff.

According to Trina Roberts, director of the Pentacrest Museums, some of these theses clearly connect to the UI Museum of Natural History‘s collections. For example, Fanny Thompson Wickham’s (B.S. ’90, M.S. ’95) thesis makes use of specimens in the Museum’s insect collection. Likewise, Leah May Gaymon’s (B. Ph. ’92 and M.A. ’95, English) thesis is based on specimens collected during the 1893 Bahama expedition. And it’s possible that she’s in this picture of students drinking coconut milk on that expedition. And that’s exciting!

Asking questions, drawing connections, building the historical record – that means something. That helps us not only tell the stories of the people who came before us, but it also helps us understand ourselves within a longer story about this school and the people who have made it what it is today, one day, one page at a time.

So, I’m thrilled to be sharing these documents with the public. And I’m really delighted to be asking people to engage not only with the work of making their handwriting intelligible to the rest of us, but also to be inviting people to learn more about the individuality of the scholars who wrote these materials. We hope people will find something interesting and engaging in these works. And we appreciate, greatly, the public’s willingness to lend a hand in this scholarly endeavor.