Chamber music has been integral to the educational and creative life of the University of Iowa School of Music for over a century. Below are a few examples, including audio clips, from 1972 to the present that allow you to experience this delightful form of music making – whether you were there to hear itContinue reading “Chamber Music at the University of Iowa: Faculty Ensembles”

Category Archives: School of Music History

BAND 141: an exhibit celebrating the history of the Hawkeye Marching Band

This Fall, come to the Voxman Music Building for BAND 141, a look at the Hawkeye Marching Band. Director Eric Bush donated a significant collection of materials from the Band’s history including photographs, drill charts, papers, scrapbooks, uniform pieces, audio and video recordings, and other memorabilia to the Rita Benton Music Library in 2020. TheContinue reading “BAND 141: an exhibit celebrating the history of the Hawkeye Marching Band”

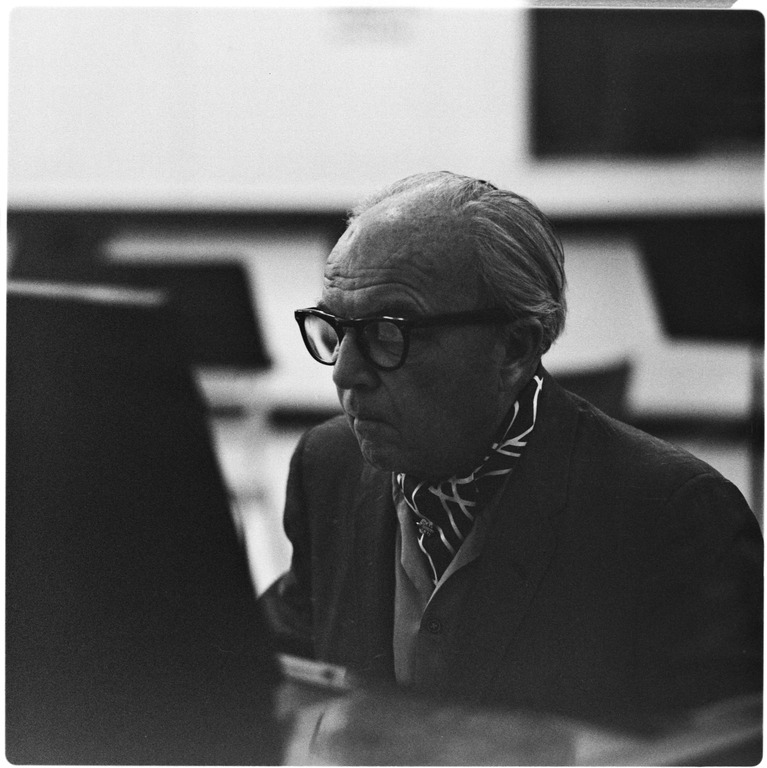

Dimitri Mitropoulos’ Music Library: From New York to Iowa and Back Again

On November 21, the New York Philharmonic Archives opened a new exhibit about Greek conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896-1960) in the Bruno Walter Gallery at Lincoln Center. The exhibit focuses on Mitropoulos’ tenure as music director of the Philharmonic (1949-1958), but also explores major themes of his overall career. Exhibit items include correspondence, photographs, and manyContinue reading “Dimitri Mitropoulos’ Music Library: From New York to Iowa and Back Again”

EXHIBIT: 95 [YEARS OF] THESES

In 1923, department chair Philip Greeley Clapp established graduate studies in music at the University of Iowa, and in 1924/25, the first students concluded their course of study with the submission of musical compositions and documents as theses. Over the last 95 years, Iowa graduates have submitted musical works, performing and critical editions, historical andContinue reading “EXHIBIT: 95 [YEARS OF] THESES”

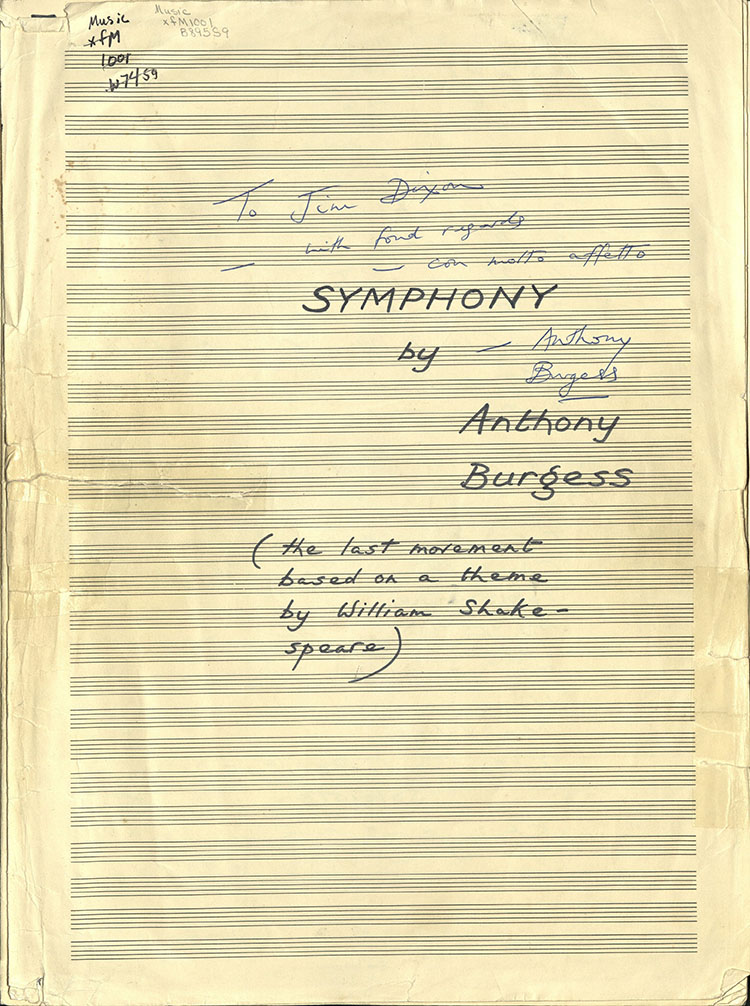

SOUNDS FROM THE FIELD – Anthony Burgess in Iowa City: How Clockwork Orange’s Author Came to Write a Symphony for the University of Iowa

by Nathan Platte The English novelist Anthony Burgess visited Iowa City in 1975 to teach at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. His course received endorsement in the “Letters to the Editor” section of the Daily Iowan. “I would like to thank the Iowa English Department for arranging such a unique class as Problems of the ModernContinue reading “SOUNDS FROM THE FIELD – Anthony Burgess in Iowa City: How Clockwork Orange’s Author Came to Write a Symphony for the University of Iowa”

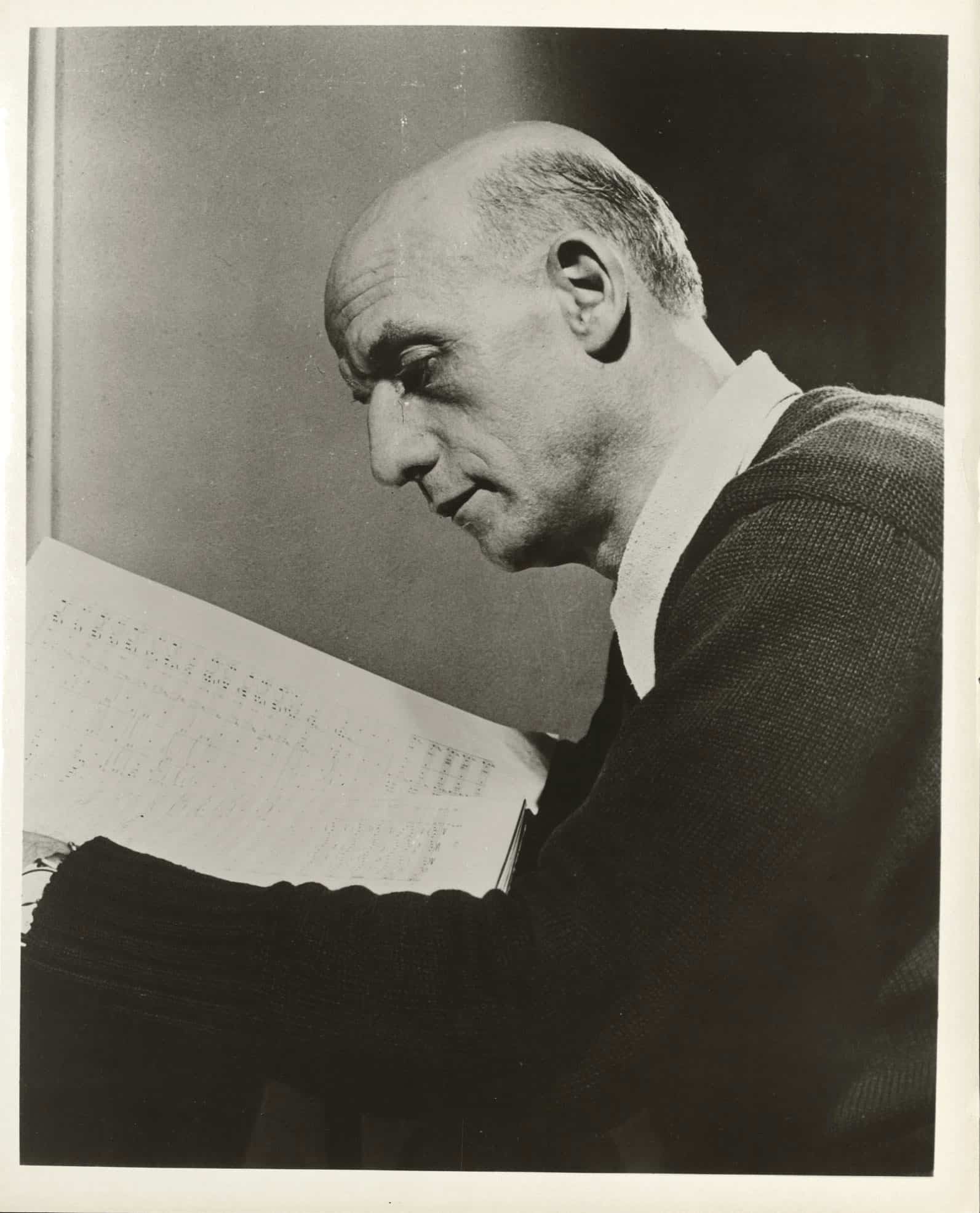

Students Investigate: A Deeper Dive into the SUI concert of Copland compositions, March 5, 1958

State University of Iowa Orchestra concert of Copland compositions, March 5, 1958Represented by original concert program and picture of Himie Voxman and Aaron Copland from the composers 1958 visit to Iowa City by Jenna Sehmann On March 5, 1958, Aaron Copland attended a concert by the State University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra as an honoredContinue reading “Students Investigate: A Deeper Dive into the SUI concert of Copland compositions, March 5, 1958”

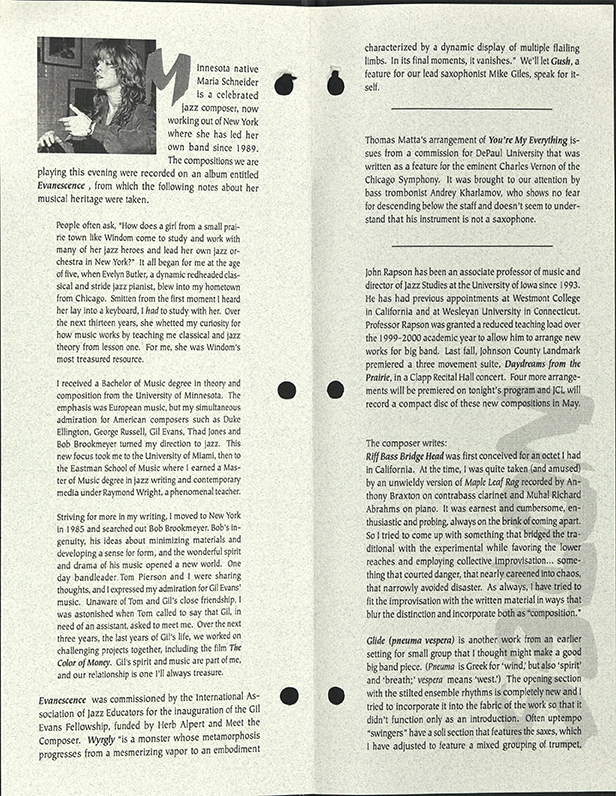

Students Investigate: A Deeper Dive into the Music of Maria Schneider

JCL Features the Music of Maria Schneider (2000) by Toni LeFebvre On April 26, 2000, Johnson County Landmark, the premiere big band of the University of Iowa, featured the music of band leader, John Rapson, and award-winning American jazz composer, Maria Schneider. Programmed were three pieces from Schneider’s 1994 debut studio album, “Evanescence” – “Wrigly”,Continue reading “Students Investigate: A Deeper Dive into the Music of Maria Schneider”

Students Investigate: A Deeper Dive into Ernst Krenek

The University Orchestra Performs Ernst Krenek, November 17, 1965 by Lisa Mumme Can works composed in the United States be considered American if they draw on European styles? When does an immigrant – and his art – become American? The November 17, 1965 University Orchestra program offers one opportunity to consider how these questions canContinue reading “Students Investigate: A Deeper Dive into Ernst Krenek”

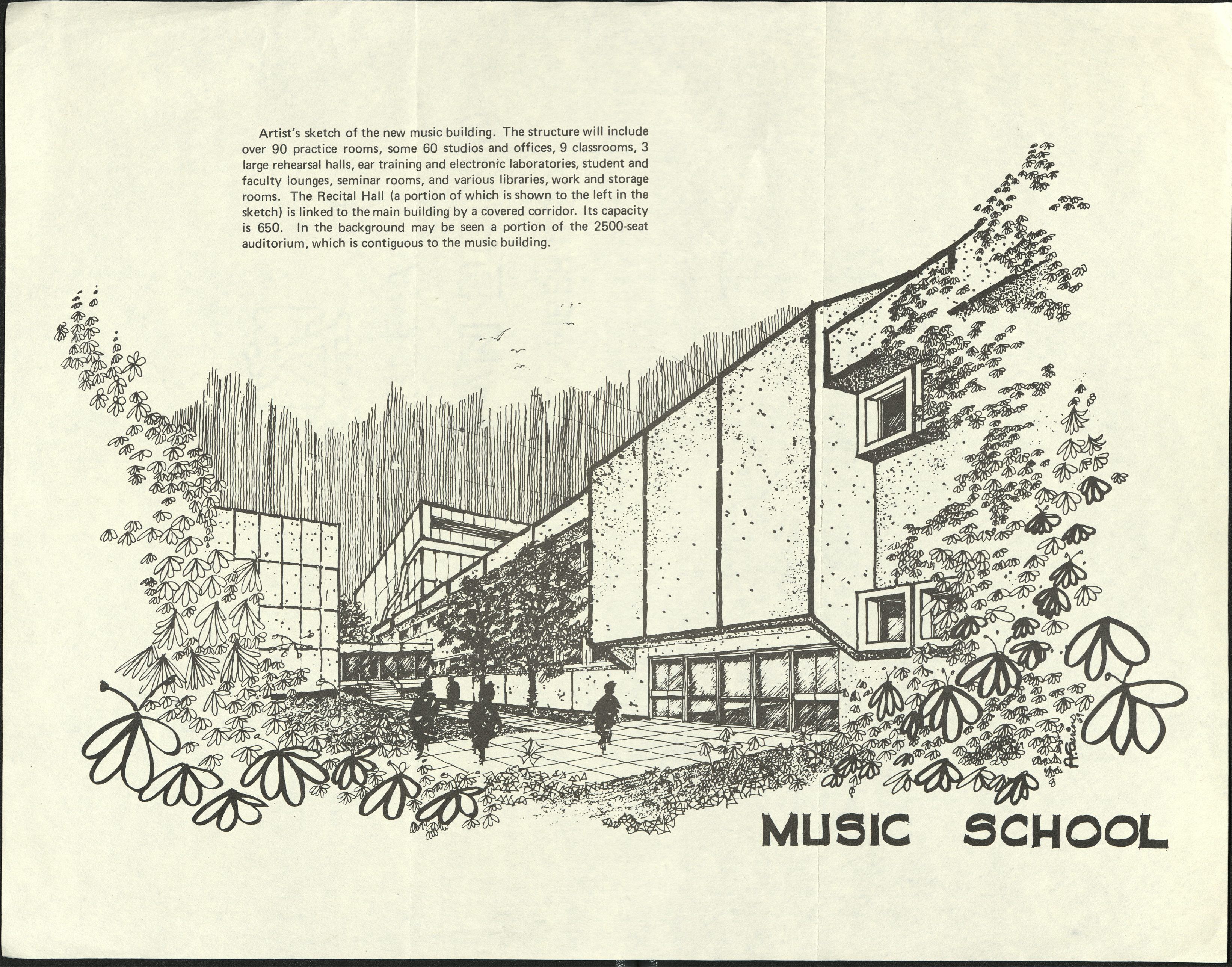

Building a School of Music

Starting on March 31, 2017, the School of Music will host three Collage concerts celebrating the opening of the Voxman Music Building at 93. E. Burlington St. “Coming Home” is the theme of the year, especially for the many alumni who have journeyed to see the new space and hear music fills its halls. Historically,Continue reading “Building a School of Music”

Re-resurrection: Mahler’s Second Symphony at the University of Iowa

Honoring the past On Wednesday evening, the University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra and Choirs will perform Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 in C minor-E flat major, “Resurrection”, marking the first School of Music ensemble performance in the new Hancher Auditorium. The selection of this work is a powerful reminiscence for many, as it was performedContinue reading “Re-resurrection: Mahler’s Second Symphony at the University of Iowa”