The project that I’m working on during my summer fellowship explores the gendered and racialized politics of the Academy Awards, more commonly known as the Oscars. This project includes a WordPress site with forms of data visualization and a series of video essays that can be used to educate a general audience but also as pedagogical tools for a gender/race studies or media studies audience. By tracking the inclusion of women and people of color in the Oscars nominations over time through various modes of visualization, I hope to demonstrate the continued lack of equality in the Academy Awards despite significant strides having been made. The importance of this project lies in its use of the Oscars to illustrate racial and gender inequality in the popular film industry as a whole. As a mainstream film award, the Oscars act as a social barometer for inequalities that occur both onscreen and behind the camera in the media industry. Recent controversies like “#OscarsSoWhite” demonstrate the significance of this lack of diversity both for those who are involved in the film industry and for film spectators who simply desire better representation onscreen.

The first few weeks of work on my project have been very exploratory, as this project pushes me outside of my scholarly comfort zone in a lot of ways. Familiarizing myself with WordPress has been its own adventure, and I’ve also been collecting the data that will be used for my visualizations and video essays. This has gotten me thinking a bit about what “data” means for scholars in different fields and departments. As an American Studies PhD student whose prior training was in English, I’m not used to dealing with “data” in its most traditional sense, unlike someone who may be coming from the social sciences, for example. Even the data that I’m collecting now, through documentation of Oscar nominees’ race and gender, is not nearly as technical or numerical as the information that would be considered data in other fields. So far, I’ve been able to stay away from using a spreadsheet, which is a relief!

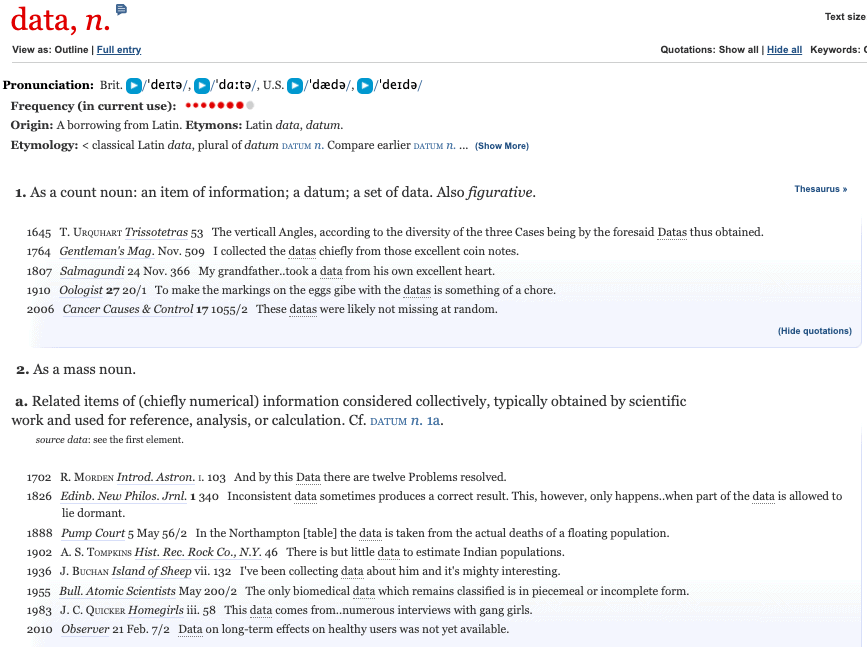

The Oxford English Dictionary defines data as “related items of (chiefly numerical) information considered collectively, typically obtained by scientific work and used for reference, analysis, or calculation.” Even here, we see a bias towards data that is numerical or quantitative rather than qualitative. But isn’t it true that my prior projects relied upon data in order to make an argument as well, even if I’d never considered that information to be “data”? If I’m writing a paper that analyzes a horror film, doesn’t that rely upon “data” such as the details of the film’s cinematography, mise-en-scéne, or editing?

Ultimately, what I’m getting at here is that my project work and data collection has me thinking about the much bigger picture of how academic fields define their work and what value is put on certain types of information, or “data.” As I experiment with a new type of work through this digital fellowship and have the opportunity to interface with people from a variety of academic fields, these are the types of questions that naturally arise!

-Laurel Carlson