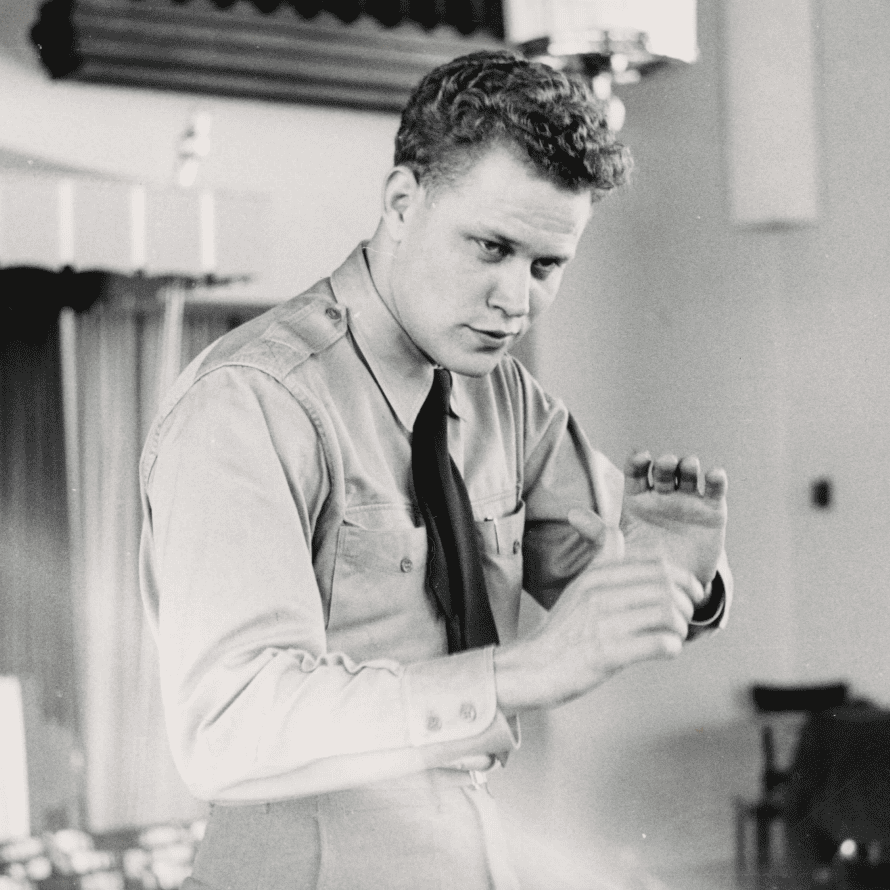

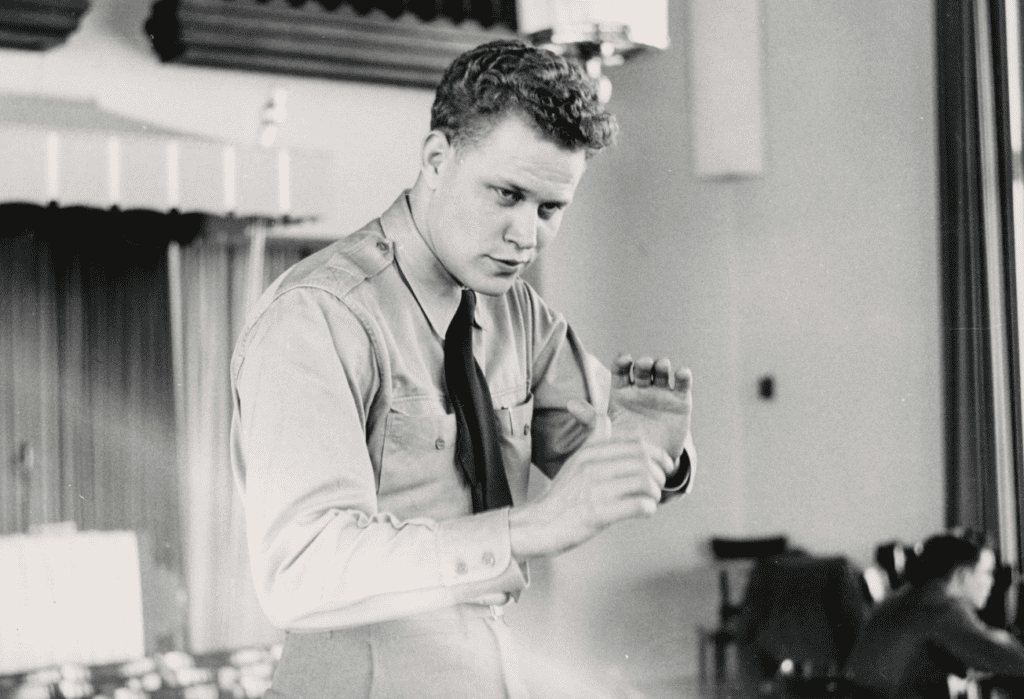

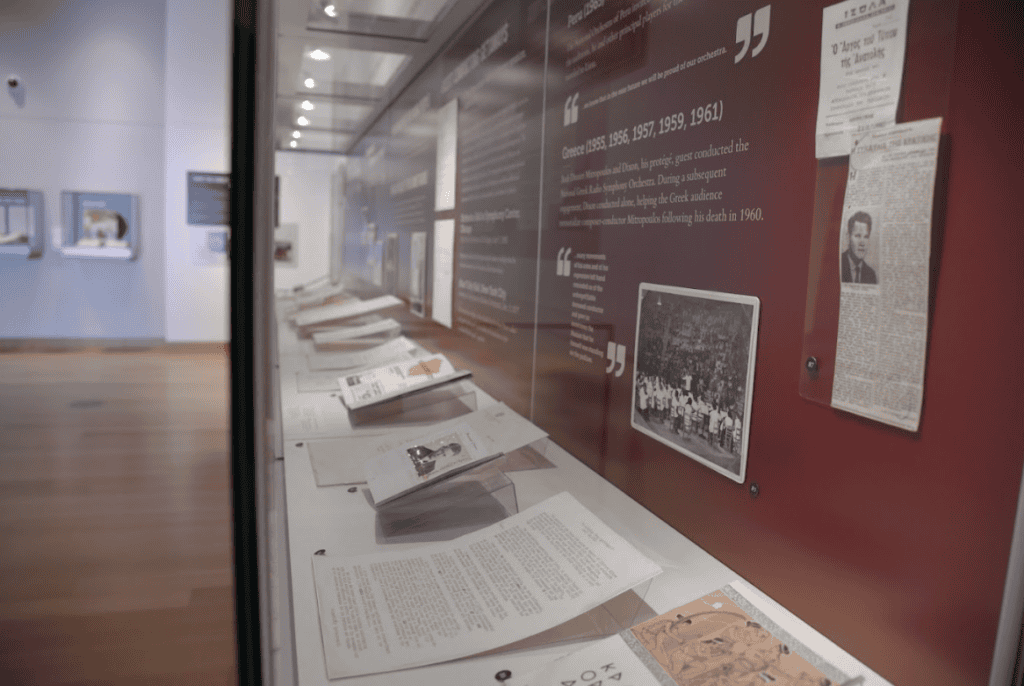

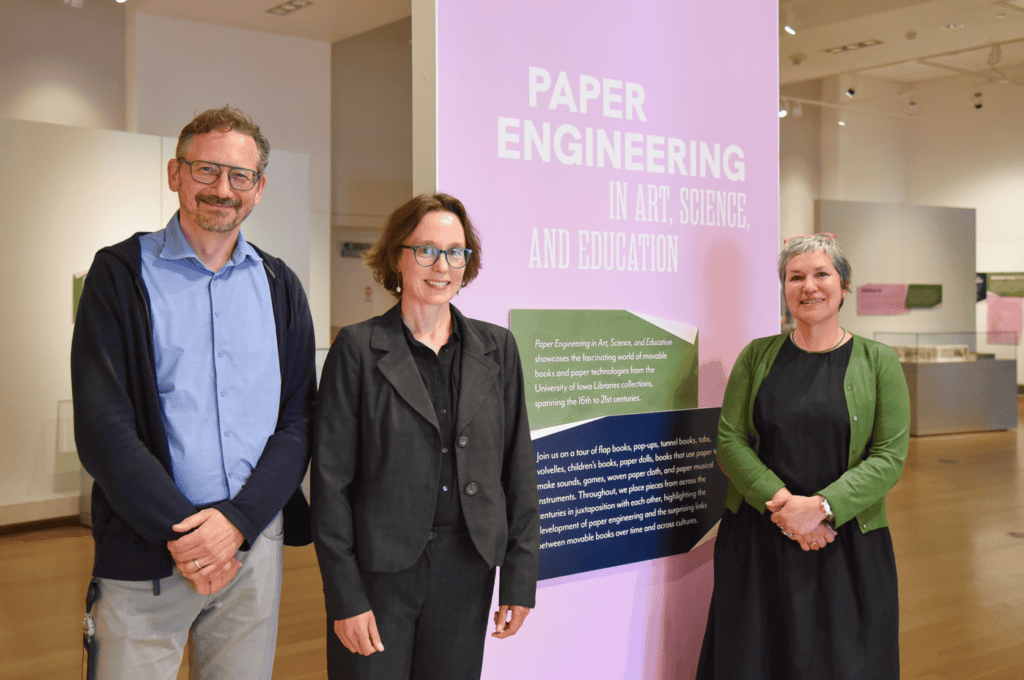

Orchestrating Community: The Public Service of Iowa Conductor James Dixon, the spring 2026 exhibition in the Main Library Gallery, provides a glimpse into the life of its namesake through stories and objects from the recently donated James Dixon Papers. From newspaper clippings and photographs to official documents and correspondence, each item on display helps piece together his adventurous international career as an orchestra conductor while celebrating his roles as a longtime director of both the University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra and the Quad City Symphony Orchestra.

Sarah Suhadolnik, assistant professor of instruction at the University of Iowa School of Music, co-curated the exhibition with Katie Buehner, director of the Rita Benton Music Library. The broader Dixon collection, now part of the University Archives at the UI Libraries, provided a strong foundation for Suhadolnik’s exhibition research.

Question: What inspired you to co-curate this exhibition?

Answer: I always listen with great interest to Katie’s tales of how the library collects the rare items it accumulates. Discussions of the work involved in acquiring the Dixon materials pushed me to develop my graduate seminar “Histories of U.S. Orchestras.” When it came time to put the exhibit together, Katie thought my work on the course would prove useful in developing the narrative for the exhibit. It did.

Q: What drew you into the story of James Dixon (1928–2007)?

A: Accessibility of, and advocacy for, public arts experiences are essential talking points in orchestral music right now. The Maestro gives us a lot to reflect on when thinking about both.

Dixon hints in some of his public remarks at frustration with the notion that an artist interested in a sustainable performance career must invest a certain amount of energy in what we today call their “personal brand.” Even though he had a New York Philharmonic conductor on proverbial speed dial, Dixon’s aversion to “selling himself,” cultivating the type of public following we now measure with social media accounts and the like, limited both the number and prestige of performance positions available to him. At the same time, orchestras were not an abstract public good to him. He operated at all times with a tangible vision of what his ensembles contributed to their respective communities and could speak very clearly and effectively about that.

Q: What has curating this exhibit meant to you as both a scholar and musician?

A: At its most personal to me, the exhibit is an ode to what I fear can get lost in conservatory-style music education. Long hours alone in a practice room can make it hard to feel enmeshed in a larger musical ecosystem. The rigors of this type of musical training can undermine a performer’s relationship with prospective listeners, and/or make attending a live performance as part of an audience into a chore.

Q: How did you approach your research in the archives?

A: Throughout, I have organized my research for the exhibit around two core objectives: firstly, to introduce the broader public to the breadth of what is available in Dixon’s collected papers; and secondly, to trace the depth of Dixon’s roots in the local community. This often meant working in multiple directions simultaneously.

To be able to accomplish the first objective, I had to understand what was in the collection, and the only way to do that was to explore what I could while it was being processed. Work towards the second objective looked a lot like storyboarding. As I got to know the collection a bit better, I collected what fragments I could of the stories waiting to be told with the materials. I built up a holistic view of Dixion’s life and work as it relates to the lesser-known history of regional orchestras.

Q: Why is it important to have this exhibit in the Main Library Gallery?

A: If the exhibit were not in the gallery, I wouldn’t have had the chance to collaborate with the amazing team that works there. I have learned more from Sara, Lauren, and the rest about public-facing scholarly work than I have from any number of papers, conference presentations, and seminars on the topic.

Q: What are some of the most surprising things you learned during your research for this project?

A: I learned a lot about what a tragedy it is to lose local news. Papers in small communities like Guthrie Center had so many subtle yet significant ways of maintaining strong bonds among close-knit residents. For instance, a lot of the local newspaper announcements I found for concerts on the University of Iowa campus included the names of students who had grown up in the place of publication.

Q: What is your favorite object in the exhibit?

A: “The Conductor’s Study,” which is more of a built environment than a singular object. It’s this element that allowed me to fully experience what the medium of exhibitions can accomplish that scholarly publication cannot.

Q: What do you hope visitors will take away from their time in Orchestrating Community?

A: I expect the pictures of Dixon’s return to Guthrie Center with the University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra to personally resonate with a lot of visitors. If they weren’t a member of an ensemble performing in a gymnasium like the one pictured, or a guest at the type of school reception pictured, they likely know someone who was. I hope visitors take a moment as they enjoy all the exhibit has to offer to think about all the people and places they are connected to because of such community music experiences.

Orchestrating Community: The Public Service of Iowa Conductor James Dixon will be on display through June 26, 2026. The Main Library Gallery is open daily. Plus, hear clips from Dixon’s conducting career online.