The UI Main Libraries Conservation and Collections Care Department presents the 2021 William Anthony Conservation Lecture Peter D. Verheyen Down the Rabbit Hole: Embracing experience and serendipity in a life of research, binding practice, and publishing September 30, 6 pm CSTVirtual, free and all are welcome CLICK HERE TO REGISTER The William Anthony Conservation LectureContinue reading “2021 William Anthony Conservation Lecture by Peter D. Verheyen on Sept. 30 at 6pm”

Category Archives: Community, outreach, education, and events

Preservation Week 2019

This week is Preservation Week, which is sponsored by the Association for Library Collections & Technical Services (ALCTS), a branch of the American Library Association (ALA). Preservation Week is an opportunity to learn about and take action to preserve collections. The theme for this year’s celebration is “Preserving Your Family History” which emphasizes the importance of preserving the collections of families, individuals, and communities in addition to those in libraries, museums, and archives.

Part Two: A Librarian’s Disaster Response Gear

By Nancy E Kraft: My Trunk Kit has expanded from a flashlight and a screw driver to include pliers, wrenches, screw drivers, a hammer, mallet, crowbar, string, twine, utility knives, caution tape, duct tape, gloves, scissors, flash Lights, a “head” light, and hiking boots. The crowbar is handy for prying swollen doors and drawers open. Wet books swell, become jammed into shelves, and often need to be tapped out with a mallet. Ideally, all items will have wood or rubber handles to protect from electrical conductivity. In addition to the trunk kit, I utilize whatever I can find at hand. Window screens are handy for drying out fabrics, thin paper and photographs. String or rope can be strung up between trees and CDs, DVDs, slides, photographs can be hung up to dry.

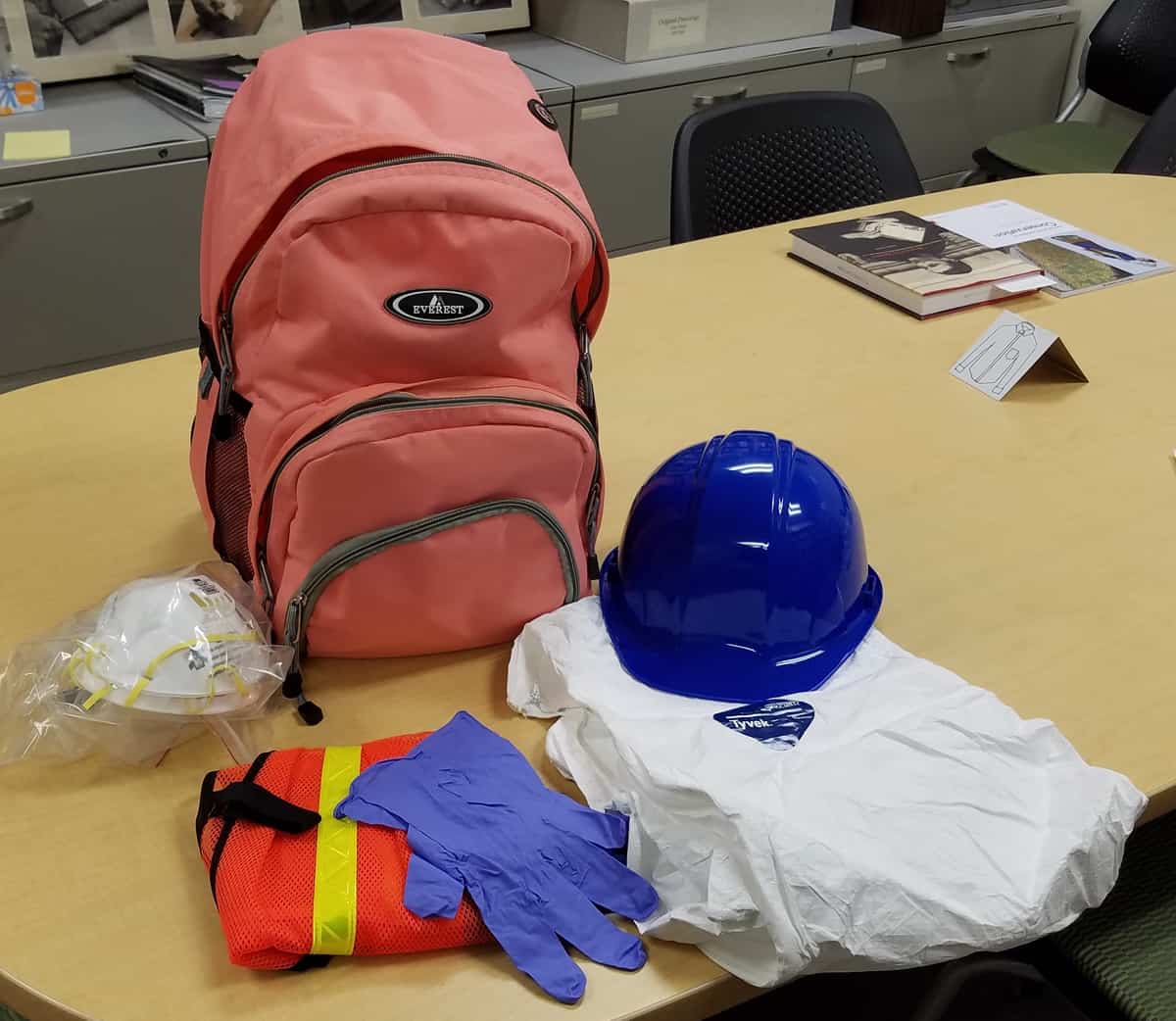

Part One: A Librarian’s Disaster Response Gear

By Nancy E Kraft: With the Mid-West Tool Collectors Association Fall meeting in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and the fact that I assisted in responding to the flood of 2008, I thought it would be interesting to highlight the personal gear I use to respond to disasters to libraries and museums. The gear can be divided into three categories: personal protective equipment, response tools, and recovery tools.

Pagan heads to Puerto Rico for cultural heritage conservation project

Candida Pagan, project conservator, traveled to Puerto Rico in early February to participate in the Helping Puerto Rican Heritage Project (HPRH).

Puerto Rico faces specific preservation challenges due to the tropical climate. Salt and humidity, along with more catastrophic weather like hurricanes, pose issues for institutions that house archives and collections. HPRH seeks to educate participants about conservation efforts in Puerto Rico while also advising conservators about care and preservation of their collections.

May Day Disaster Response Drill

Tuesday, May 1, 2018 Special Collections and Preservation/Conservation staff concluded a series of disaster preparedness and response training with a disaster response drill. We divided up into four teams. Each team retrieved, rinsed, and packed out the material found in a wet, muddy pool of water. Staff had to decide what to keep and whatContinue reading “May Day Disaster Response Drill”

If Objects Could Talk History Harvest at the African American Museum of Iowa

In higher education, we often equate student life and campus life. Last year, I found myself questioning this notion on my frequent shortcuts through the student center on campus. Absent from most of the archival photos hung in the student center’s hallway chronicling milestones in the building’s history are black students. Student life does notContinue reading “If Objects Could Talk History Harvest at the African American Museum of Iowa”

Shakespeare At Iowa Items Under Wraps

Friday, August 26, 2016 We’re keeping everything under wraps for the opening day of the Shakespeare First Folio and Shakespeare At Iowa Exhibit. As items were prepared for the exhibit, they were wrapped so not even staff could take a peek. Here some of the books are sitting in front of their individually crafted cradles.Continue reading “Shakespeare At Iowa Items Under Wraps”

Documenting and Treating Scrolls: Part 2

Friday, July 15, 2016 Submitted by Katarzyna Bator and Bailey Kinsky Dry cleaning is the first step in most, if not all conservation treatments. Loose dirt and soil buildup collects on exposed portions of the object, in this case on the outermost part of the scroll. Additional dirt can find its way onto the surfaceContinue reading “Documenting and Treating Scrolls: Part 2”

Documenting and Treating Scrolls: Part 1

Thursday July 7, 2016 Submitted by Katarzyna Bator and Bailey Kinsky We are both graduate students at Buffalo State College Art Conservation Department. We are spending the summer at the University of Iowa Library Conservation Laboratory partaking in a practicum of treatment and care of library and archives material. Using theory and techniques learned duringContinue reading “Documenting and Treating Scrolls: Part 1”