There is a question I’ve continually returned to over the past eight weeks. What is the relationship between the past and the present? When someone thinks of reparations, the first question that might come to mind could be, what is Black America owed? However, throughout my summer fellowship, I found how one answers the former question directly impacts how one answers the latter. This seemingly innocuous question drives the digital research project I pitched to the Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio at the beginning of 2020. Little did I know, while I posed the query in the context of Black reparations, the question would take on newfound significance in the wake of a pandemic that disproportionately harms Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities, alongside a renewed sense of urgency concerning police brutality and anti-Black violence in the United States, but also globally, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade. How we perceive the past and the present, as either distant foes or closely connected twins, dramatically influences how we understand the reason a virus can discriminate, or what might appear to be a “new” problem is actually something most Black communities see as the fabric of their lived experience—par excellence for the United States. Indeed, our sense of time, and its relationship to racial (in)justice, is a valuable space to (re)think how our present racial disparities blossom out of the fertile soil of the past.

Contemplating reparations through the lens of time drew me to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ essay “The Case for Reparations.” He plays with time and draws upon it as a resource to open up the debate over reparations. His article sparked a national conversation over Black restitution not seen in over a decade when it was published in 2014 that continues to this day. At the start of the summer, I set out to create a non-chronological/non-linear timeline that mirrors the timeline jumping in Coates’ prose. As he narrates a case for reparations, he moves about the timeline of reparations, jumping from 1923, to 1968, back to 1783, and up to 2001. The movement of going forward and backward invites an alternative approach to the relationship between the past and the present. My project, tentatively titled Disrupting the Reparations Timeline, functions as a temporal guide through Coates’ article, hopefully equipping a user with a different perspective on the connection between the problems of our past, and the problems of our present, while also learning more about the history of anti-Black violence in the United States.

With only a week left of my summer fellowship, I am now putting the finishing touches on a website complete with an introduction page for the timeline and an extensive resources page if someone wants to learn even more about the histories covered in the timeline. At the beginning of my journey, I was anxious about all of the possibilities. I vacillated between nervousness that creating the non-chronological timeline I envisioned would be too complicated to not doing “enough” over eight weeks of summer. In the end, I have completed a 1.0 version of my digital project I am excited to refine and test as I look ahead towards what the life of my digital project might entail.

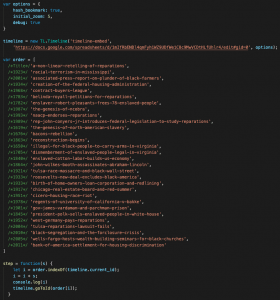

The biggest obstacle I overcame involved configuring a way to use the Timeline.js platform to sequence a non-chronological timeline. If you remember from my earlier post, I was in the reasonably daunting position of combing through hours of JavaScript tutorials and trying to figure out a way around this problem. With the help of my tremendous Studio contact, Nikki White, we devised a way to instruct the timeline to move along an order I manually entered into the code. At first, we both assumed it was going to be a pretty arduous and messy process. However, we managed to find a relatively easy and slick fix.

Timeline.js has a particular functionality that allows you to create a unique “id” or URL for each event on the timeline. We created a simple function that asks the timeline to recognize its place in the timeline, and when a user clicks the “NEXT” or “BACK” buttons, the timeline either moves one step forward or backward. Then, we stored the desired order of events (as they appear in Coates’ essay in a non-chronological fashion) in what is called an “array” that essentially houses the entire sequence. When someone clicks the navigation button, they are essentially moving forward or backward in that array. It took a great deal of time, research, and creativity to come up with this solution. In the end, Nikki helped me create a non-linear timeline that catapults a user forward and backward with the click of a button.

In reflecting upon my summer in the Studio, the experience taught me a great deal about adopting a digital humanities framework that thinks about the back-end as much as the front-end. I came into the fellowship overly concerned with the front-end—what the website might look like, how the timeline would function, and what a user would gain from playing on the site. However, I quickly learned, starting from the back-end is a far more fruitful way to make sure the front-end of the project holds up. In other words, it was through the process of having to create a JavaScript function for the timeline, to coding in HTML each element of the website, I gained a newfound appreciation for a holistic approach to digital humanities project development. I’m incredibly thankful to Nikki for demoing almost every aspect of the back-end of my project, walking me through each step, and answering all of my questions, so I could leave this summer with a thorough understanding of why my project works. I started the fellowship thinking that Nikki and I would form a partnership where I played in my sandbox, and she played in hers. I quickly learned that a collaboration, where we both played in the same sandbox, taught us both a lot more.

I feel incredibly fortunate and privileged I had the opportunity to work with the Studio and create Disrupting the Reparations Timeline. Learning how to create functions and basic website styling through code was an experience I was certainly not prepared for, but one I am happy I got. I was challenged and pushed out of my comfort zone. Through my research, I gained an even more nuanced understanding of the political history of reparations in the United States and gained a new perspective on how digital spaces can aid or hinder subversive/disruptive representations of anti-Black violence. The process of having to code around a problem—the prevalence of a linear/chronological sensibility towards time—taught me just as much about the racial/colonial ideologies that undergird public literacies around time, as it did about the potential digital tools can play in leveraging alternative spaces for understanding, outside the realm of Western/Eurocentric notions of time. The Summer Fellowship through the Studio provided a profound space to make mistakes, troubleshoot, and try out new things. Having eight weeks to play in a digital humanities sandbox fostered a low-risk environment with a high payout. Regardless if I ended up with a “finished” product or not, I gained valuable insight into my research program and my potential future endeavors in the public digital humanities.

Cheers, until next time!

– Andrew Boge

If you would like to get in touch about this project, please email me: andrew-boge@uiowa.edu