During the Great Depression, youth, a group young enough to be in school, while old enough to enter the workforce, worried American political leaders. The fear was that they would follow the path of youth in Germany or the Soviet Union and bring drastic change to the American political system. To alleviate the suffering of America’s younger generation, the Roosevelt administration created many youth-focused programs within the New Deal, such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the National Youth Administration (NYA). These programs sought to aid youth by giving them work to do, money with which they could help support their families, and education. This educational component often involved retracing what youth missed from dropping out of school early, as well as providing vocational training to make them more competitive in a job market that was already teeming with qualified applicants. Along with academic and vocational education, the CCC and NYA often included civic education in their programming to promote youths’ commitment to American democracy and create a generation of engaged citizens. While the job training upset some labor unions, educators, and businessmen, it was the political education that created the largest concern over the work these youth facing programs were undertaking.

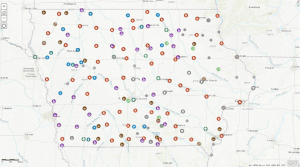

During the mid to late 1930s, there was constant anxiety that the youth needed help to avoid Fascism and Communism, while simultaneously the New Deal efforts sometimes resembled European programs that indoctrinated youth. To gain a better understanding of everyday American’s view on these programs, I have been working on mapping the worksites of the NYA and CCC as they overlap with regions of Iowa intensely hit by the Depression. I intend to use the visualizations to understand more clearly how aid to youth on the ground materialized and highlight areas of disproportionate assistance or lack thereof.

I began by creating a spreadsheet of NYA and CCC reports, which included the site, sponsors, and number of youth working on the projects in Iowa. I showed this draft map to the director of the CCC/POW museum in Iowa; they mentioned they would love to have a version they could share with their visitors. Upon finding this out two weeks into my project, I realized that I need to start thinking of this project as a more free-standing project than as merely a visual component of my research findings. In modifying the narrative sections of my work, I’m finding that I can adapt my digital project that transmits information to varied audiences.

The conversation with the museum led me to investigate similar mapping projects to try and get a better understanding of how they are structured and presented. In thinking about making a website or page, I am still concerned about the staying power of the project beyond my time at the University. I spoke with my advisor about possibilities, but ultimately, I think it is down to what the museum feels most comfortable using to ensure that the project gets used and I will be meeting again with them this week. I will continue work in the next few weeks to create a Storymap that tells both the broader history of the CCC and NYA but also shows Iowa specific projects and the conditions in Iowa that necessitated the programs. I imagine in the coming weeks I will also be exploring the basics of creating a website and gaining a better understanding of what all that would entail.

-Luke Borland