This series features the work and research of UI students. The following was written by Cecil Campbell, exhibition and engagement student lead for the Main Library Gallery.

Cards are found in many games, across time and place. They can be adapted to appeal to different ages, different playing styles, and even different commercial franchises. The history of card games is very much one of evolution and innovation. Though the 52-card deck has existed since the 15th century, thought to originate in France, the oldest playing cards are thought to date back to the Tang Dynasty during the first millennium. Though the cards that we’re familiar with today are made of plastic-coated cardstock, Tang Dynasty playing cards were made of paper, printed with woodcuts, and doubled as a form of currency.

In his History of Playing Cards, Rodney P. Carlisle talks about the rise in popularity of playing cards across Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries:

“Writings from this period document card games being played in Spain by 1371, and in France and Switzerland by 1377. The early decks were handmade works of art available only to the rich, but the introduction of the mass production of paper around 1400, coupled with the popularity of woodcut printing, quickly led to the creation of inexpensive decks for the general public.”

Cards have a wide range of uses. Historically, they’ve been used as collection items, to tell fortunes, for currency, and of course, for gambling, having been associated with gambling for as long as they’ve been around. Card players from the Tang Dynasty would have used the cards themselves as betting money, raising the stakes by literally gambling away the hands they played with. As card playing spread across Europe, some governments found themselves more troubled by this new pastime than they’d expected. Carlisle wrote that “[in 1397] the prévôt of Paris declared a workday ban on recreations that could distract workers; in addition to cards, dice, tennis, and all forms of bowling were named in the decree.”

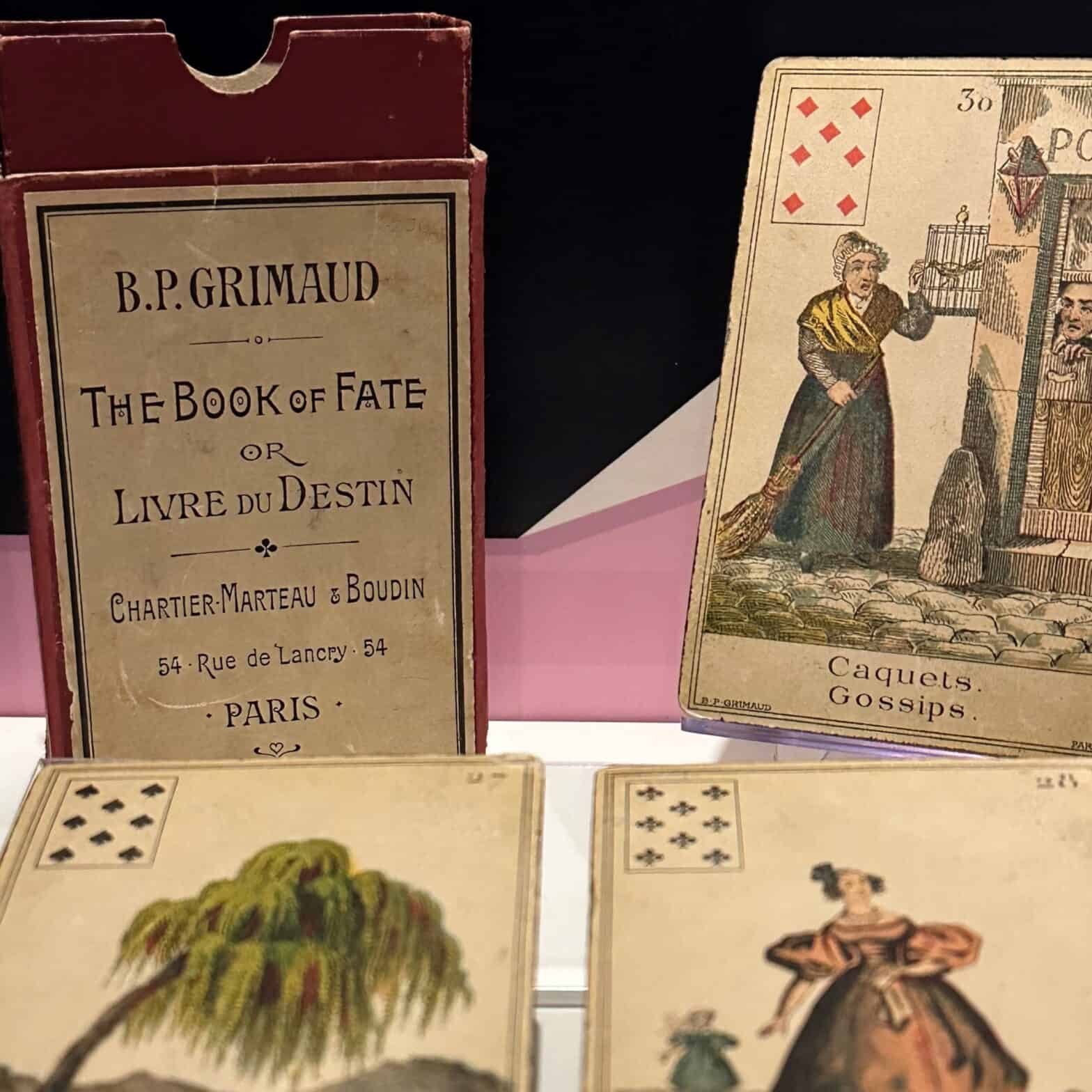

Possibly the only use for cards as famous as gambling is fortune telling. Tarot cards are a popular form of fortune telling, along with oracle decks, though fortune tellers have also been known to use regular card decks to tell fortunes. Le Livre du Destin, or The Book of Fate, is a French 32-card oracle deck from 1900. It features a wide variety of different archetypes of people, in typical fortune telling fashion, all meant to relate to some potential aspect of a person’s life.

Before we can understand how to use The Book of Fate, we must first understand how tarot and oracle decks work. Tarot is more universally known and also follows a more rigid system of rules than oracle decks. Tarot decks are made up of 78 cards, the most well-known of which are the Major Arcana. Major Arcana take the form of archetypes, such as “The Empress,” “The Fool,” “The Hermit,” or “The Hanged Man.” These cards represent broad life lessons and challenges that we may face, like going through a loss, a change in direction, or new beginnings. Sound vague? They’re meant to be! The answers that tarot gives are broad and are accepted to not take shape for days to weeks or even months after a reading.

So, what’s the difference between tarot and oracle reading? Oracle decks are much more freeform, with no standard number of cards and no consistent imagery from deck to deck. Typically, oracle cards rely on our immediate intuition for interpretation, and are better suited to answer more specific, “yes/no” type questions. While a tarot reading invites the reader to meditate on what the answers could mean, oracle cards require a good deal less overthinking. So, since The Book of Fate is an oracle deck, we should ask questions that are less vague and more to-the-point than what we’d ask if we were reading tarot. Additionally, the types of cards in the deck will let us know what types of answers we’ll get. The cards in The Book of Fate are based mostly on common social roles, characters, or themes seen among English or French society in the late Victorian era, such as “a soldier,” “a man of law,” “a fair-haired girl,” or “a business letter.”

Of course, while their use might be more straightforward than tarot, oracle readings do still take a little interpretive work from the user. After all, the point of fortune telling decks is that they can be applied to and interpreted by just about anyone, regardless of circumstance or background!

The Book of Fate is on display in the Main Library Gallery’s Paper Engineering in Art, Science, and Education exhibition, which showcases the fascinating world of paper technologies. Curated by Giselle Simón, Damien Ihrig, and Elizabeth Yale, this interactive exhibition invites visitors to explore paper dolls, flap books, pop-ups, tunnel books, volvelles, and books that use paper to make sounds while learning about their historical and contemporary significance. It is open to the public through Dec. 19, 2025.

Further reading:

“History of Playing Cards.” In Encyclopedia of Play in Today’s Society, edited by Carlisle, Rodney P., 289-93. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2009. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412971935.n170.