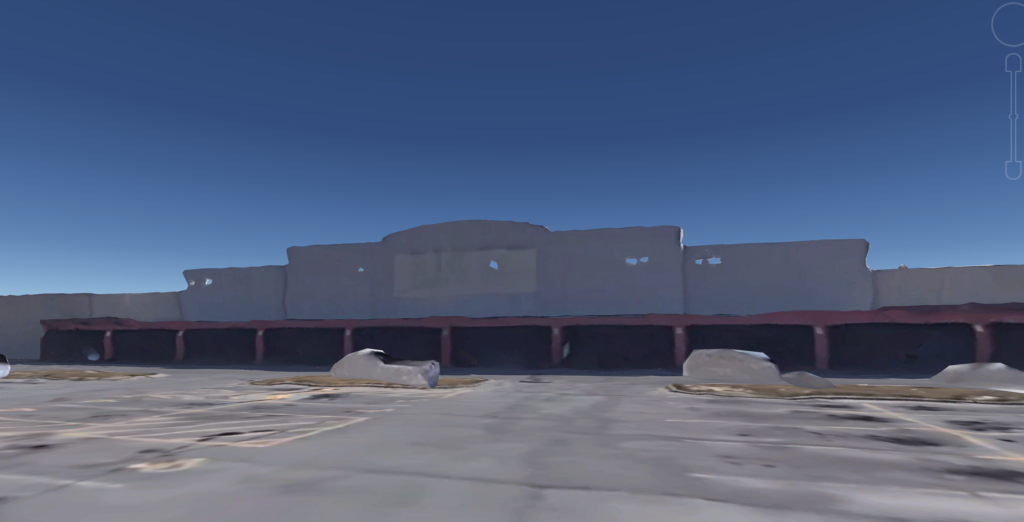

I’ve spent more time than I ever could have imagined thinking about Kmart this past year. Ever since a friend sent me a YouTube clip of a man reading the last announcement at a Kmart store (‘the store will be closing, forever, in 5 minutes…’) and I scrolled through the video’s thousands of elegiac comments, I’ve been following that initial instinctual pang of salience, trying to put my finger on exactly why the phenomenon of Kmart melancholy is interesting to me—and maybe could be, to others, too. Early on, I read YouTube comments and clicked through to commenters’ accounts, discovered people making videos of their Kmart collections, their rooms full of Kmart posters and signs and baskets; I discovered all these guys recording videos of closing and abandoned Kmarts, walking their radically few viewers through every minute detail of a particular store, its history, its end. I went on Facebook and joined the ‘Crazy about Kmart…’ fan group. The central question I was following seemed to be: how exactly could anyone love something as banal as Kmart? I wanted to understand. I had little interest in the store itself; Kmart was a stand-in for any seemingly unlovable cultural entity, any outsized unrequited libidinal attachment—a metaphor. I started interviewing Kmart fans, including Eric, the creator of a fully-functional 1:1 virtual reality Kmart in the popular online community VRChat. Kmart was a vector/vessel for nostalgia. It wasn’t a metaphor anymore. Certain kinds of people get so attached to Kmart precisely because it is endangered, right? I thought about the last day one might spend in a foreign city, when the nearness of departure sharpens everything to a fine point. There was a short essay by Freud I had read in college called ‘On Transience’ in which Freud describes a walk through the countryside with Rilke. The two thinkers discuss what it means to counter melancholy in the face of life’s transience and flux. This would be my way in. The essay would be about time. I rewrote it from scratch. I read biographies of Freud and Rilke. I read and read and wrote. Kmart was about abiding the passage of time, about a certain kind of relationship to the past, about being time-bound, time-vexed, time-hurt. Ha. I read some book called The Philosophy of Time, copy + pasting dozens of paragraphs from the book into various documents. But surely the Kmart thing was really about unrequited love? The essay would surely be at least 100 pages. I searched ‘Kmart’ on JSTOR, twice. My ‘research’ folder blossomed. 300 pages. And then I saw Meta’s Super Bowl ad, in which the metaverse’s “futuristic,” “cutting-edge technology” was blatantly marketed to the American public as a nostalgic escape from the scary, ever-changing present. The cognate to VR Kmart was obvious. I pitched The Drift. They were interested. I would rewrite the essay to be an argument against nostalgia—or something—from a psychoanalytic perspective, with an eye to how Big Tech caters to conservative regression. “I think we have a lot more of this coming –retreating into a futuristic past–as more and more supposedly stable coordinates are thrown into jeopardy,” I wrote. I didn’t know what I was talking about, one bit. And then I applied to the Digital Studio. I forgot to write The Drift back. The project would be about virtual reality. I would research the history of VR as a vehicle for memory, for memorialization. Wasn’t there a Titanic VR experience? Kmart, the Titanic, same idea. I would focus on Eric’s virtual reality Kmart, figure out how it works, why he made it. I researched, I searched, I clicked around, I read. I sat in front of the open ‘research’ folder on my computer and thought But okay isn’t this about middle-class nostalgia really, isn’t this about saying goodbye to the banal amidst larger crises? Kmart is about climate change, about grief and mourning. Death? No—what it is now is this: taking the digital scholarship I have unwittingly and semi-wittingly done—the interviews, the video recordings of VR Kmart, the images and images and videos and notes and files and folders and pitches and quotes and drafts and drafts and drafts of this slippery multifaceted strange and boring thing—and turning it all into something real, something beyond my head, beyond my iCloud drive, beyond all these otherwise real things. I have beautiful blurred memories of all this writing, all this digital scholarship, all these instances of Kmart—but now I suppose it’s time to finally get started.