I have been working on an accessible version of my dissertation research on Anishinaabe Two-Spirit history. I’ve spent the last year learning and expanding my skills with audio editing and podcast hosting as well as managing a website, so I did not realize how steep the learning curve for setting up another podcast would be. Now, a month into the project, I recognize several important factors.

By tracking my hours, I have learned that an episode of my previous “Bagpipe and History” podcast takes 30-60 hours to create. The new show will take longer, as it involves scheduling meetings and researching guests as well as getting extended readings of primary sources from voice actors. I have a new appreciation for project management and the importance of completing most of these components before I begin releasing episodes. I have also learned how much Digital Scholarship for historians involves conventional archival research.

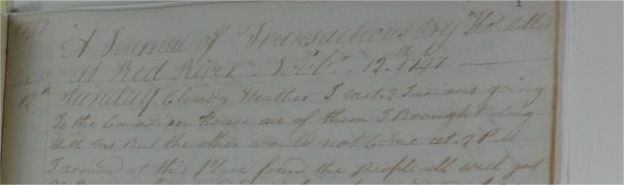

The largest number of written records that exist from the time and place I am studying were created by European fur traders. My archive of their records is not computer-searchable; previously I spent a full semester transcribing a single handwritten journal (see figure 1) into a spreadsheet so I could begin to ask questions of it digitally. While that would lead to some fruitful scholarship, it is unclear how helpful it would be for gaining a better understanding of Two-Spirit history.

Figure 1: The First Page of Thomas Miller’s 1797-1798 Post Journal from the Red River.

I chose to transcribe a post journal from a time and place in which I knew a Two-Spirit person lived. Ozaawindib was Naagokwe (a being who appears as a woman) and was generally just referred to as a woman by her fellow Anishinaabeg. That entire transcribed post journal refers to only one woman, and not by name, and there is no reference to Ozaawindib in any recognizable way. The authors of these records were so blinded by their rigid colonial heteropatriarchy that even if they observed relationships or people who might identify as Two-Spirit today, they may not have recognized that. This does not mean it is not important to analyze them.

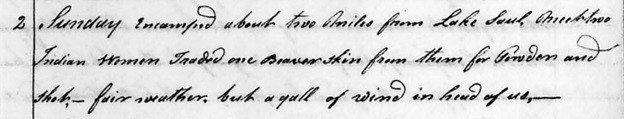

For example, fur trader John Sutherland’s trading post journal from the Saskatchewan River in 1795 is typical of Hudson’s Bay Company records in that all the women he wrote of were described solely through relationships to men or children, with one exception. (see figure 2)Figure 2: John Sutherland’s Entry for August 2nd 1795, Indian Elbow post Journal.

On August 2nd Sutherland wrote about meeting “…two Indian women” who “Traded one Beaver skin … for powder and shot.”3 In an archive filled with monotonous discussions of the weather and trade with men, this entry stands out.

This evidence goes against popular understandings of Indigenous women and their roles in the fur trade. Although some historians argue both trading furs and buying ammunition would be men’s activities, these women did both. Sutherland’s description is so short that it is difficult to interpret, but this account may show a same-sex couple trading furs they trapped to get ammunition to go hunting, or this could be two women who are merely buying ammunition for a man who is indisposed. While brief and ambiguous, this may be the only reference to a “lesbian” Two-Spirit Anishinaabe household which has survived in the colonial record. I hope this is not the case and as I conclude looking through my archive, I will be able to add a more robust entry for my dissertation and public-facing podcast.

-Jeremy Kingsbury